By Jason Martin

While global central banks are shifting their stance and following the U.S. Federal Reserve's footsteps in taking a less dovish stance on monetary policy, experts are warning that complacent markets may have created a bubble in fixed income that will soon undergo a severe correction.

The Fed clearly took the first step back in December 2015 when it raised rates for the first time since the crisis, although the U.S. central bank had to wait another year before making its next move.

So far this year, the Fed made further increases in both March and June, bringing the federal funds target rate to its current range of just 1.00% to 1.25%, while hinting that it will likely hike once more this year and also begin to move forward with balance sheet normalization.

Recent surveys of experts show that consensus is leaning for the Fed to move ahead with its plans for tapering, as the reduction in its purchases of bonds is known in September when Fed chair Janet Yellen will be able to explain the process in the press conference following the monetary policy decision.

Economists widely anticipate the Fed to also hike rates once again in December, although markets themselves remain skeptical, pricing in just a 40% chance of an increase, according to Investing.com’s Fed Rate Monitor Tool.

BoC, BoE and ECB set to follow Fed in return to normal policy

Though the Fed took the first step in the removal of extremely accommodative policy, markets have begun to see indications that other major central banks are also shifting towards a less dovish stance.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) raised interest rates for the first time in seven years last month while the Bank of England (BoE) is divided with two of its eight members already arguing that it is time for the UK’s monetary authority to hike in order to combat rising inflation.

Also recently causing waves in markets, investors are preparing for the European Central Bank to possibly announce in September or October its own intentions to begin the tapering of its asset purchase program next year.

Market players were however disappointed on August 16 when a report citing central bank sources said that ECB president Mario Draghi would steer clear of a delivering a new policy message at the U.S. Federal Reserve's Jackson Hole economic symposium in Wyoming near the end of August.

In a sign of the times, markets must adjust their outlook from central banks’ endless supply of free money to a realization that monetary authorities recognize that the end is coming for the current global easing cycle.

“Bond markets have been conditioned to thinking that whenever there was a slip-up in risk appetite somewhere and a tightening in financial conditions, the central banks would come to their rescue,” RBC Capital Markets fixed income strategists recently said.

“Now it’s almost as if the central banks are engineering the tightening in financial conditions,” they postulated.

Investors may have been slow to react as only 48% of investors recently surveyed by Bank of America-Merrill Lynch believe that global monetary policy has become “too stimulative” for recent improvements in the world economy.

However, these experts did note that the reading was the highest proportion since April 2011.

Policy normalization is not “hawkish”

In a situation marked by central banks only just beginning to pull interest rates off record lows and consider dampening their asset purchases, markets, and media, may be too quick to apply the term “hawkish” to the mere suggestion of removing highly accommodative policy measures.

A prime example came when media latched on to remarks from ECB president Mario Draghi back at the end of June in Sintra that reflationary forces had replaced deflationary ones in the region.

Markets, lured by “hawkish” headlines, skipped over Draghi’s additional comments about the need to continue with a considerable degree of monetary accommodation and his insistence on maintaining that self-same policy.

“As the economy continues to recover, a constant policy stance will become more accommodative, and the central bank can accompany the recovery by adjusting the parameters of its policy instruments – not in order to tighten the policy stance, but to keep it broadly unchanged,” Draghi stated, in what could hardly be considered to be a “hawkish” stance.

Even at the extreme, the fact that the ECB chief recognized that deflation was no longer a threat in the euro zone could hardly be defined as anything other than “less dovish”.

Yet, “hawkish” was the word that hit headlines and pundit commentary, sending the yield on the German 10-year bund on its largest jump since 2015 and, what was then, the best day for the euro since April.

ECB “sources” had to run to the rescue the following day to point out that Draghi had been “misinterpreted”.

Not unlike the ECB, major central banks may well have begun to focus on bringing the easing cycle to a close, but policies remain a far cry from being “traditional”.

As an indication of just how far global monetary authorities are from “normal”, Bank of America-Merrill Lynch economists recently noted that the five major central banks cut rates by an average of 350 basis points and that the current average nominal policy rate is currently at just 50 basis points, suggesting that current levels would leave them unable to respond to another crisis. Far from “normal”.

Nontraditional policies had also kicked into high gear with, according to BofAML, the U.S., Swiss, British, Japanese and euro zone central banks having balance sheets totaling roughly $15 trillion, compared to just around $4 trillion at the start of 2008.

Winding down, but not eliminating, asset purchases

While the Fed has jump-started the normalization process with regard to interest rates, the BoC has followed suit with one move, while the BoE sees just two of its eight members voting for a hike, none of the major central banks has even begun to unwind their balance sheets.

The Fed is also widely expected to kick start the process in October with the official announcement arriving at the September meeting.

Markets are also waiting for September to see if the ECB hints at the euro zone monetary authority’s own plans to begin to “reduce”, not even eradicate, its monthly asset purchases.

The process has only just begun and is a logical consequence of expectations that the global economy will continue to improve coupled with healthy financial markets.

Indeed, U.S. stocks continued to hit record highs despite the fact that the Fed has increased rates twice this year while promising balance sheet reduction and a further hike before year-end.

However, the pace of normalization on the global level remains in question.

“Lackluster price pressures and structural problems, such as low productivity growth and high income inequality, indicate that this policy normalization will be very gradual,” Robeco’s head of global fixed income Kommer van Trigt said in a recently published quarterly outlook.

“So don’t expect central banks to step on the brakes aggressively and derail financial markets,” he explained.

Market reactions so far

Despite the apparent shift in central banks’ outlook, equity markets appear to be unfazed. The global benchmark S&P 500 has chalked up gains of 8.3% year-to-date, the blue-chip Dow has risen 9.7% and the tech-heavy NASDAQ Composite leads the pack with gains of 15.5%.

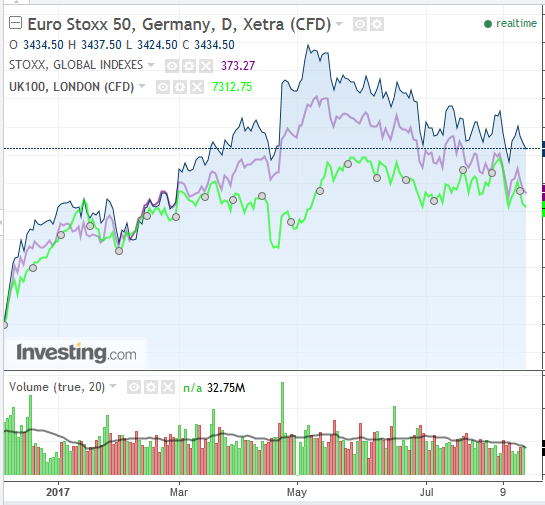

In Europe, the benchmark Euro Stoxx 50 is 4.2% higher so far this year, while the wider pan-European Stoxx 600 also shows a 3.3% advance. London’s FTSE 100 follows behind European counterparts with gains of 2.3%.

In Asia, the Shanghai Composite registers solid year-to-date gains of 5.9%, while oddly enough, Japan’s Nikkei 225 is a laggard, rising just 1.5%, despite the fact that the country’s central bank is forecast to be one of the few monetary authorities that may not undertake any removal of accommodation over the forecast horizon, even though the Japanese economy recently took the lead in growth of the G7 advanced economies.

Yet despite the positive performance in stocks, safe haven assets haven’t shown an inverse reaction with gold up nearly 11% so far in 2017, while sovereign debt prices continue to hold their ground.

The yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury saw a wild ride last year after hitting a historic closing low of 1.358% in July as prices soared on the government debt, only to turn around and hit a 2016 closing high of 2.606% in mid-December just after the Fed followed through on its second rate hike since the crisis.

But prices on Treasuries, which run inversely to yields, have since recovered, pushing the yield back down to around 2.183%.

The move was not entirely due to recent political tensions between North Korea and the U.S. as yields were already dropping despite two more rate hikes from the U.S. central bank and further promises to forge ahead with policy normalization this year.

Bond yields, which move inversely to prices, would normally rise on the prospect of tighter monetary policy through higher interest rates or a scaling back in quantitative easing measures.

Bond bubble?

G+ Economics chief economist Lena Komileva recently commented that bonds were looking expensive.

“The risk premium on European high-yield bonds over German Bunds has fallen to the lowest since 2007, matching levels that preceded the global financial crisis,” she recently wrote in an opinion piece for Financial Times.

In fact, according to data from BofAML, more than 60% of European corporate debt with lowly BB credit ratings now yields less than U.S. government debt of comparable maturities, suggesting that investors see less risk in junk bonds from the Old Continent as compared to those issued by Uncle Sam.

The nuances have spawned numerous commentaries over the likelihood of a bubble in the bond market.

Former Fed chair Alan Greenspan recently warned that there was a bubble in bond markets that was about to burst.

“The current level of interest rates is abnormally low and there's only one direction in which they can go, and when they start, they will be rather rapid,” Greenspan told CNBC at the beginning of August.

The following week, JP Morgan chief exec Jamie Dimon followed Greenspan’s lead, although he attempted to downplay the call to panic.

“I’m not going to call it bubble,” he said in an interview with CNBC, “but I wouldn’t personally be buying 10-year sovereign debt anywhere around the world.”

Phoenix Capital Research chief market strategist Graham Summers made reference to Dimon’s comments and warned that “if sovereign bonds are in a bubble, every asset under the sun is in a bubble”.

Summers said that a bursting of the bond bubble would, like in Greece, result in entire countries going bust and highlighted that while the pre-crisis housing bubble was about $14 trillion in size, the global bond market is north of $100 trillion.

The aforementioned BofAML survey also showed that a bond market crash was at the top of money managers’ tail risk concerns with 28% of those questioned saying they most feared a correction in the bull market that has taken hold since the global financial crisis.

A rout in bond markets may also cause ripples in stocks.

“The direction in equity markets in the second half of the year could largely depend on where the bond market heads and that investors may need to reprice to higher bond yields,’’ BNP Paribas analysts warned.

For the moment, four of the five major central banks are shifting their stance with regard to highly accommodative measures.

With the Fed at the head of the pack in an attempt to return to a more normal state of monetary policy, the free money spigot on the global level will slowly be closed off as central banks become less dovish.

BlackRock portfolio manager Emanuella Enenajor warned that the Fed has been “telling the markets loud and clear to get ready for balance sheet normalization.”

“They have telegraphed this for months, so it shouldn’t be a surprise if in September, they announce the change in policy,” she said, indicating that it would be “a continued gradual exit from a highly accommodative framework.”

If markets have been too complacent, ignoring the fact that central banks are preparing to put an end to a decade of easy money, what would otherwise be a normal correction in both bonds and stocks could gather momentum and become a full blown crisis.