By Geoffrey Smith

Investing.com -- Once upon a time, sagas were exciting, exaggerating and immortalizing the heroic feats of Viking warriors, slaying monsters, winning demi-goddesses as brides and what-not. But there was a catch. Given the general lack of entertainment on long northern nights in the Dark Ages (aside from drinking and brawling), there was no pressure on the writers and performers to keep it short. Over time, as audiences became more demanding, the saga came to represent something dreary, repetitive and seemingly endless.

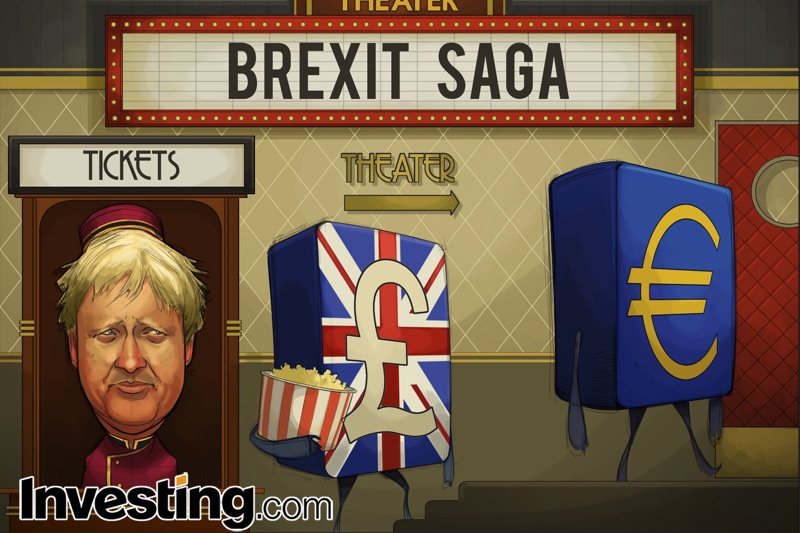

Which is why the term fits Brexit so well. After bursting onto the international news scene in 2016 as a raucous, populist rebellion against consensus thinking, it has morphed into an unspeakably boring slugfest of bureaucrats arguing over the mutual recognition of regulations, state aid and – God help us – fishing rights.

Fishing, which accounts for some 0.05% of Eurozone GDP, is reportedly the last big stumbling block to a deal on a trade relationship worth $1 trillion a year and much else besides – such as freedom of movement and security cooperation – on which no price can sensibly be put.

Neither the hyperbolic nationalism of the U.K. government nor the preening self-righteousness of the European Union can dress this up as anything other than a piece of political theater gone mind-numbingly and tediously wrong that most people would rather forget. A YouGov poll published on Tuesday showed that Brits, who famously voted 52%-48% to leave in 2016, now think by a margin of 51%-40% that it was a bad idea.

Too late. The end is in sight. The 11-month transition period that has allowed both sides to pretend that the U.K. hadn’t left the bloc in January comes to an end in nine days’ time. After that, in the absence of a deal, the two sides will have to apply tariffs and quotas to each other’s goods, like it or not: the World Trade Organization’s rules don’t allow anything else.

For nearly half a decade, foreign exchange markets have worked on the assumption that: 1) Erecting trade barriers where none previously existed would be a negative for both sides; 2) The U.K. would not be able to deliver on Brexiteers’ promise to bring back the glory days for the British economy (quite what kind of glory was never quite spelled out, but the odds of a fresh windfall from using gunboats to blow open the Chinese market for Indian opium must be quite slim, at any rate); 3) The high costs of No Deal would ensure that common sense prevailed to make the best of a bad job.

Little has happened to change any of those calculations in that time. As such, the discount applied to sterling has been relatively constant: it’s still trading around 10% lower against the euro and dollar relative to its level before the 2016 referendum. On both sides of the Channel, there are governments determined on spending big to reflate the economy, and central banks determined to accommodate them with equally big bond purchase programs.

If – IF – common sense can prevail and No Deal can be avoided, history would suggest that sterling is now somewhat undervalued against the euro. Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s regular fund manager surveys certainly suggest that U.K. assets – starting with the pound itself - are ‘under-owned’ and technically set up for a rebound. However, for that to be sustained, the U.K. has to prove that the Brexit process hasn’t permanently damaged U.K. productivity relative to the euro zone’s. The burden of proof is going to be heavy.