- Markets are expecting a lot of rate cuts this year

- The mortgage squeeze looks less worrisome with rate cuts on the horizon

- The Chancellor can expect £12bn extra "headroom"

- Real wage growth is improving

- The jobs market is cooling gradually, while savings have fallen in real terms

- Bank of England implications

Markets are expecting a lot of rate cuts this year

This Friday, we'll get another dose of UK monthly GDP data. And while we're expecting a November bounce after a disappointing October, much of the reporting will likely focus on the possibility of a technical recession through the second half of last year. A second-consecutive 0.1% fall in GDP is still possible in the fourth quarter, but that's hardly much to write home about.

The broader point is that the economy stagnated through much of last year. And more importantly, there are some reasons to be a little more optimistic about 2024.

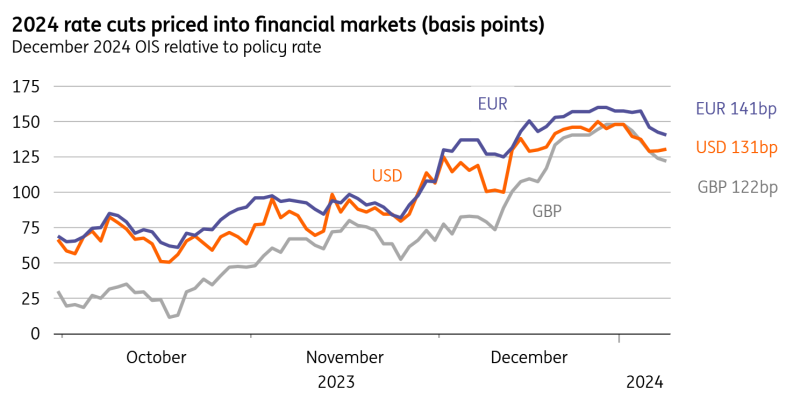

The UK is not alone in receiving a welcome boost from sharply lower market interest rates. Investors are now pricing five rate cuts from the Bank of England this year, and that's only slightly less than what's priced for the ECB or Federal Reserve. But there are two ways the fall in market rates could have a more tangible impact on UK growth than elsewhere.

Markets have ramped up rate cut bets

The mortgage squeeze looks less worrisome with rate cuts on the horizon

The first relates to mortgage rates. This has - rightly - been highlighted as an area where the transmission of rate hikes differs in the UK to elsewhere. The vast majority of UK mortgage holders are on fixed rates, and that has helped Britain avoid the more immediate consequences of higher rates compared to places like Canada or Sweden. Both have a high proportion of floating-rate debt and both have seen a larger hit to house prices and related economic activity.

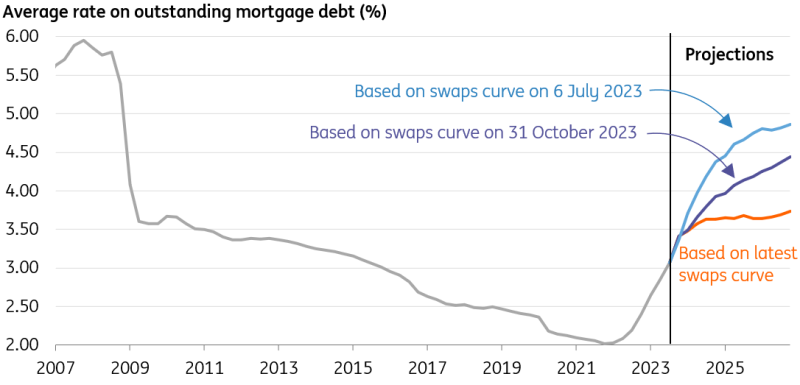

But unlike France, Germany or the US, where homeowners are more likely to fix their rates for decades, the vast majority of UK lending is fixed for five years or less. The result is that roughly 20% of British homeowners are set to refinance this year.

With many households having refinanced already, the average interest rate paid on outstanding mortgages has climbed from around 2% to 3.3% as of November. Back in July, when markets expected the UK Bank rate to stay above 5% for at least two years, that average rate on existing lending looked set to climb to 4.5% by the end of 2024 as more and more homeowners refinanced away from low interest rates locked in pre-pandemic. Last summer, quoted rates on new mortage lending surpassed 6%, and remain above 5%.

But with several rate cuts now priced, lenders are slashing rates rapidly. We therefore think the average mortgage rate on outstanding lending hasn't got much further to climb and we expect it to reach 3.6% at the end of this year, only a slight increase on where it is currently. Remember that only a quarter (28%) of households actually have a mortgage, and if only a fifth of them are refinancing this year, the impact on the wider economy shouldn't be overstated.

Average mortgage rates are set to rise less aggressively in 2024

The Chancellor can expect £12bn extra "headroom"

In fact, so far households have actually seen a net increase in interest income as the Bank of England has raised rates. Partly, that's because savings rates have risen more readily than average mortgage rates. But it's also because households now have a similar quantity of interest-bearing deposits as they do liabilities, in contrast to the past 30 years or so where the latter has dominated the former.

You'd expect the net interest income story to become more negative as savings rates fall and the passthrough of higher mortgage rates continues. And the distribution of those income-generating savings is largely concentrated among higher earners. Nevertheless, it does still act as a bit of a counterweight to the ongoing mortgage squeeze.

Lower market rates are also good news for the government. Ahead of an expected November general election, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will be hoping to use his Spring Budget on 6 March to unveil tax cuts. Fortunately for him, the fall in both short-dated and, to a lesser extent, long-dated market rates/bond yields since November's Autumn Statement should unlock £12bn extra "headroom" by our estimates. That is extra money that he could, if he chooses, spend while still meeting his fiscal rules, and comes on top of the £13bn already available from November.

In other words, there's likely to be just shy of 1% of GDP worth of tax cuts that could be available, much of which would likely go on income tax if press reports are accurate. That could boost growth this year by, say, 0.2 to 0.4ppts, depending on what was announced. It is worth caveating that by saying that in order to meet its fiscal rules, the government is baking in a lot of tightening in subsequent years, including real-terms cuts in several spending areas.

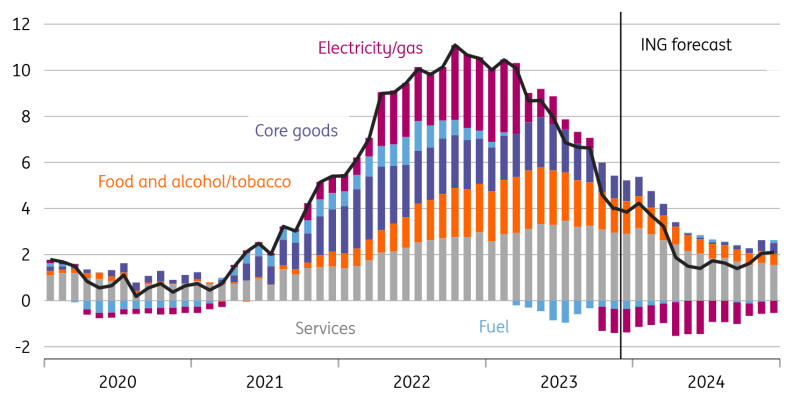

But a more modest mortgage squeeze and prospect of potential tax cuts come alongside a backdrop of positive real wage growth. Headline inflation is set to fall to 1.6% in May on our current forecasts and stay below target until November. Some of that is linked to an expected 15% fall in household energy bills in April, more than offsetting the 5% increase last week.

Headline inflation set to hit 1.6% in May

Real wage growth is improving

By contrast, average earnings growth is falling much more slowly. The BoE's survey of Chief Financial Officers (CFO) shows that wage growth expectations haven't really changed for the past year. Even so, given the jobs market is cooling, we suspect private-sector pay growth can fall to the 4% area in late spring/early summer, down from 7.3% now. But that means it's still higher than inflation, and remember too that those on the National Living Wage will see a near-10% rise in wages in April.

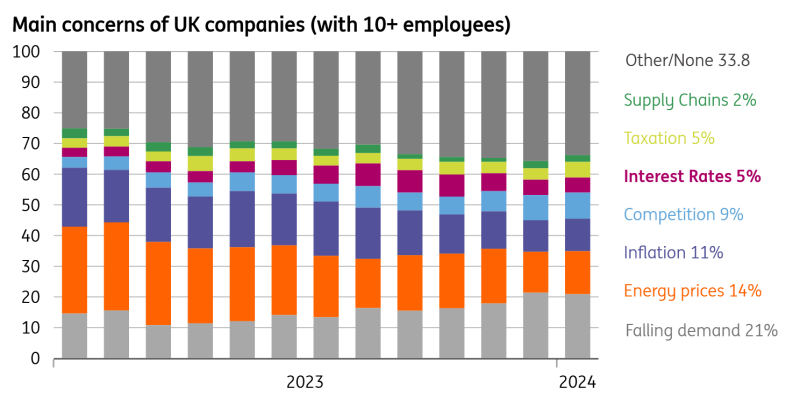

None of this means we should expect a dramatic or imminent acceleration in UK growth. There's still an open question as to how higher rates will feed through to businesses this year. We know that small businesses have already felt the full force of rate hikes, given that most lending is on floating interest rates. But larger corporates appear to be more shielded, and the Bank of England reckons that refinancing risks this year are relatively limited, something that will have been helped by the sharp fall in market rates. Only 5% of businesses say higher interest rates are their biggest concern, according to ONS survey data. Nevertheless, it's an area with more limited data, and if businesses do come under greater strain, we'd expect greater pressure on the jobs market.

How businesses rank their top concerns

The jobs market is cooling gradually, while savings have fallen in real terms

Admittedly, the jobs market is also an area with limited visibility, given recent reliability issues with the unemployment data. Improved figures are expected by Easter, but we know that unfilled vacancy numbers are falling quickly and will probably be back to pre-Covid levels by the summer. We expect the unemployment rate to drift higher this year, but not enough to drag the UK into a recession. This is, however, the major risk for this year's outlook.

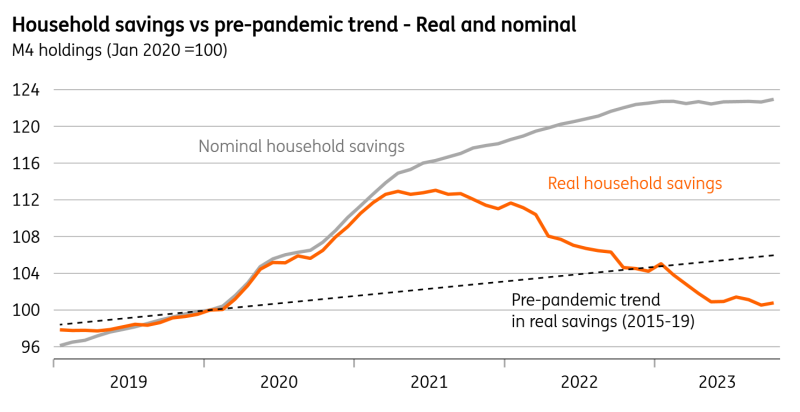

Finally, there are questions about the availability of savings to boost spending this year. At face value, UK consumers still have a large war chest of "excess savings" where their US counterparts have spent them. And the headline savings ratio from the GDP figures rose through last year and stands above pre-Covid levels at 10%. But looking at data on household liquid deposits in bank accounts and adjusting for inflation, we see that the level of real savings sits below the pre-Covid trend. It's a similar story for corporates. So while balance sheets of both households and companies looks reasonably solid, the savings story isn't is a reason to get carried away on this year's growth outlook.

Real household liquid savings have fallen below the pre-pandemic trend

Bank of England implications

All in, we expect growth of 0.5% for 2024. That implies modest but positive quarterly growth through this year. For the Bank of England, stickiness in wage growth and services inflation, as well as the likelihood of a fiscal boost in March, potentially means rate cuts will come a little later than markets expect. We're sticking with our current call of an August cut, with 100 basis points of easing through the remainder of this year.