Key points

- The money available for tax cuts – so-called “headroom” – now equals £18bn, up from £13bn in November, according to our estimates. That's lower than our estimates a few weeks ago, in light of the repricing of Bank of England rate expectations.

- Tough pre-existing commitments to rein in spending, as well as a desire to leave a safety buffer in the budget, leave limited room for tax cuts.

- Cuts to income tax, depending on the scale, would make it more likely that the Bank of England waits until the summer before cutting rates.

- We estimate there’s a 40 basis point risk premium in 10-year gilt yields, suggesting markets aren’t totally immune to UK fiscal risk.

The chancellor's room for tax cuts has narrowed

UK Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has made it abundantly clear that he intends to cut taxes at the Spring Budget on 6 March. But with markets more cautious about the extent of Bank of England rate cuts, the chancellor will have less money to play with than he’d hoped just a few weeks ago.

Exactly how much the Treasury can spend or give away in tax cuts is linked to the concept of “headroom”. This is a gauge of how easily the government will meet its main fiscal goal of seeing debt start to fall as a percentage of GDP in five years’ time.

Back at November’s Autumn Statement, the OBR judged that the chancellor had £13bn left over in headroom – or put another way, money that could in theory be spent/given away in the fiscal year 2028/29. That £13bn was what was left over after accounting for giveaways on both personal and business taxation totalling roughly £20bn per year (0.75% of nominal GDP), including a cut to National Insurance in January.

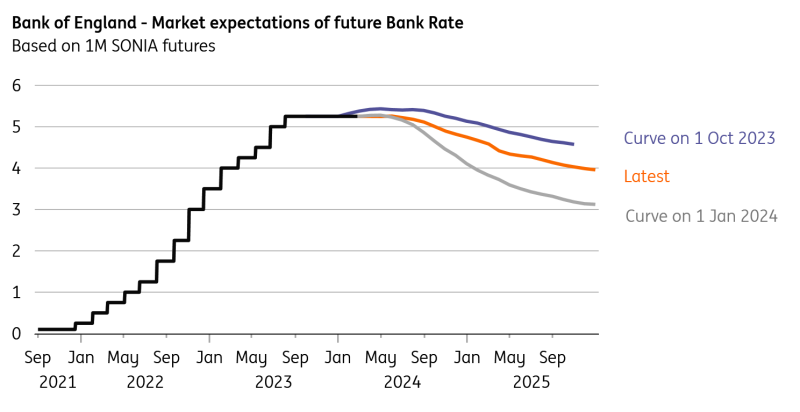

In the weeks that followed November’s announcements, market rates tumbled as investors priced in rate cuts – and back in January we estimated that this would double the headroom available for the chancellor at the March budget. That’s because lower market pricing for Bank Rate and long-term government borrowing costs reduce estimates of future debt interest repayments.

Some of that gain will have since evaporated, in light of the investor rethink on global interest rate cuts. But based on market pricing alone, we suspect the chancellor’s headroom will still have increased by roughly £5bn – so totalling around £18bn. That’s because Bank Rate expectations and 20-year gilt yields priced for four to five years’ time – the time horizon relevant for the fiscal rules – are still down by roughly 30-40 basis points since early October (which is what the OBR’s November forecasts were based on).

BoE rate cut expectations have risen but remain below October levels

A 2p cut to income tax is possible but tricky

So what could that buy the chancellor? Well for reference, a 1p cut to the basic rate of income tax is slated to cost roughly £7bn/year. If we’re right on the amount of headroom, then the chancellor could perhaps get away with a permanent 2p cut, though that wouldn’t leave him much left over.

The situation is tight. And it’s possible our estimate of headroom is too optimistic. Small changes to a range of other economic assumptions can easily offset the impact of lower rates. The Times reports that the chancellor has been told by the OBR that the headroom hasn’t increased at all since November, and in fact may have slightly fallen.

The other issue is that no chancellor ideally wants to spend all of his headroom, in case the economic environment changes for the worse before a future budget. Previous chancellors have typically opted to maintain £20bn+ in headroom for exactly that reason.

Further spending restraint looks unrealistic

That leaves the Treasury with a choice. It may well need to scale back some of its tax-cutting plans, and The Telegraph reports that the chancellor is rowing back on an ambition to cut the basic rate of income tax by 2p. But given political pressure for tax cuts ahead of a likely election this year, he may be tempted to impose more spending restraint to help maximise the headroom available and get his tax cuts through. The FT has reported that this is under consideration.

But this isn’t a particularly realistic option either. Remember that in order to win back markets after the 2022 budget crisis, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt promised sweeping reductions to previous spending plans. Those changes didn’t kick in immediately – and indeed won’t do until after the election. But what matters for the fiscal rule is that they are imposed by the five-year point.

Since that budget, the chancellor has been able to reap the benefits of higher-than-expected tax revenues owing to higher inflation, and the Spring Budget will enable him to spend some of the public finance boost from expected rate cuts. But so far we’ve not seen the corresponding changes to spending plans to adapt to the costs that higher inflation will impose.

The result is that away from things like health and defence, several government departments are facing steep real-terms spending cuts in future years. Public investment is set to fall sharply as a percentage of GDP too, something that doesn’t bode well for the UK’s pre-existing productivity challenge. Adding even more spending restraint therefore looks challenging.

The impact on the Bank of England and rates markets

Talk of tax cuts inevitably triggers memories of the 2022 “mini budget” crisis, where UK government borrowing costs rose precipitously following a package of unfunded measures designed to boost growth. Back then the issue was not just the measures themselves – which were not funded - but also the then-government’s signal that it would be prepared to cut taxes still further at future budgets despite the market stress. Investors were also concerned by the apparent sidelining of the OBR in the budget process.

The situation today looks very different. Tax cuts in March will be implemented within the framework of the fiscal rules and with OBR oversight. Admittedly, it’s possible that funding tax cuts today with unrealised and potentially challenging spending cuts tomorrow may raise a few eyebrows among investors. But the reality is that this approach isn’t new and it has been the case at successive budgets both under the current and under previous chancellors, and up until now markets haven’t been fazed.

Still, fresh tax cuts could still apply some upward pressure on yields. Sizable cuts to income tax would add further impetus for the Bank of England to keep rates on hold a little longer, in the current environment of sticky inflation and tight labour markets. Frontloaded tax cuts, funded by lower spending further out, could see the short end of the curve nudge higher.

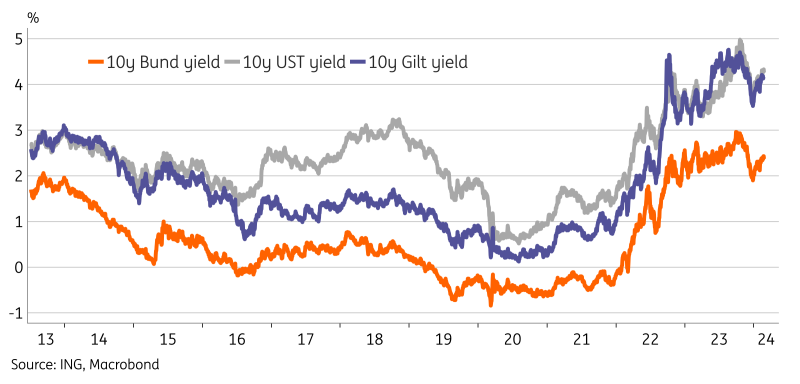

UK 10-year borrowing costs versus the US and Germany

Long-end yields could see some upward pressure from increased issuance expectations, and greater volatility could translate to a higher term risk premium. That said, borrowing has been tracking below OBR forecasts in the current fiscal year, in part because of lower gas prices. With the public finances tight and therefore more vulnerable to revenue headwinds, there’s a risk of greater yield volatility. The forthcoming election is also a risk, though so far both the major parties appear keen to fight on platforms of fiscal sustainability.

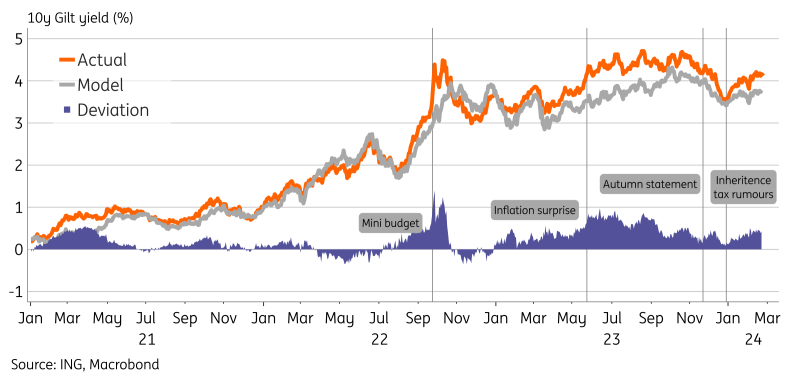

A fair value model using global factors and domestic macro drivers shows that 10-year gilt yields have mostly been on the high side since the mini budget two years ago. The announcement of the mini budget triggered the sharpest deviation from fair value at around 60bp. The Autumn Statement, where fresh tax cuts were announced, prompted an immediate widening of around 10bp from fair value, too.

Point estimates from models are never perfect, but these readings do indicate that government spending plans are on the watchlist for markets. The fair value 10-year gilt yield would now be around 40bp lower than current levels. The latter probably already includes a risk premium for the uncertainty around budgeting and the elections. As such, the current pricing provides a bit of a buffer against further yield rises.

Fair value model suggests 10y Gilt risk premium

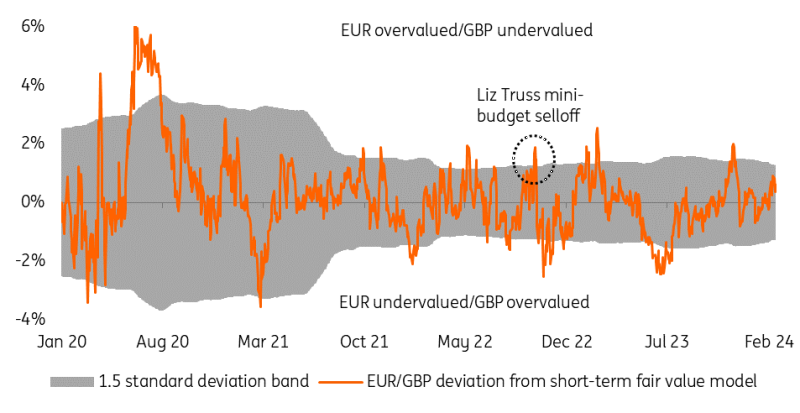

The impact on FX markets

When it comes to FX markets, current market conditions could not be more different than those that prevailed at the height of the Liz Truss debacle. Back then, GBP/USD implied volatility surged to 18% - similar to spikes seen on the Brexit vote and the Covid shock - and GBP/USD traded as low as 1.05. Today, implied volatility is close to 6% and the FX options market seems relatively relaxed about the 6 March UK Budget. It only prices a 57 USD pip range for GBP/USD on budget day, compared to 48 USD pips for a normal day.

These quiet conditions have actually benefited sterling in outright terms too. Sterling has the second-highest implied yields in the G10 space and is the only G10 currency to deliver a positive total return against the dollar this year. Continued investor interest in the carry trade should keep sterling reasonably well bid. And given our medium-term fair value calculations that GBP/USD is some 7% undervalued and that the dollar will roll lower later this year, we remain happy with a 12-month target at just over 1.30.

Were Chancellor Hunt to misread the mood of gilt investors and cause another upset, sterling would again come under pressure. Short-term models suggest a 2% sell-off in sterling could happen quite easily were investors to again demand a risk premium of sterling asset markets. Looking at the relationship between gilts and sterling back in 2022, a 20bp widening in the GBP-USD 10-year yield spread would be associated with a 1.5-2.0% weakening in GBP/USD.

On the positive side for sterling, there is some speculation that Chancellor Hunt is looking at improving incentives for global multinationals to list in the UK or for British savers to direct investments towards UK asset markets as well. These measures probably will not quite extend as far as the US Homeland Investment Act – a major support for the dollar – but should be monitored nonetheless.