The first rate cut isn't far off

Financial markets are warming to the idea of a June rate cut from the Bank of England, and it’s easy to see why.

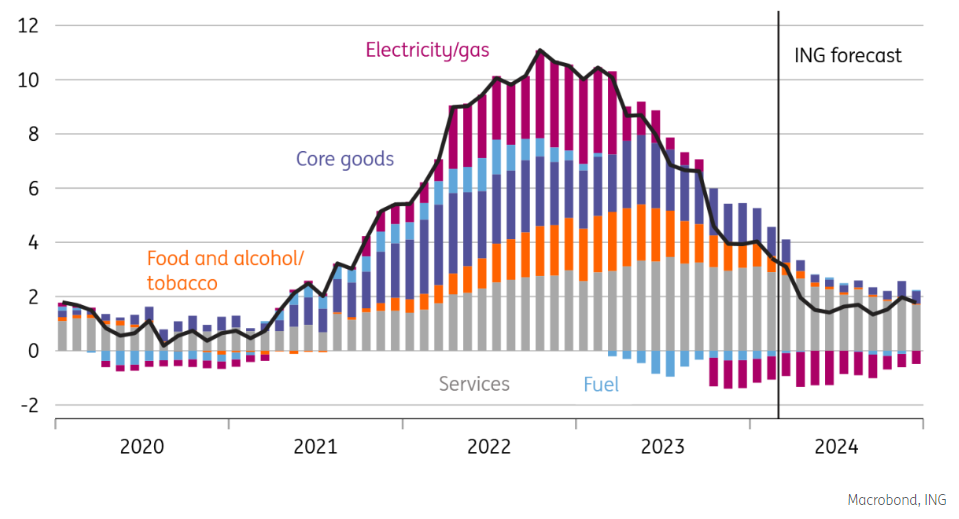

It’s virtually 'nailed on' that headline inflation will fall below target in the second quarter, and we reckon it will be down at 1.5% ahead of the June meeting. BoE hawks will point to food and energy as major culprits, but the optics of sub-target inflation with interest rates north of 5% present a growing communication challenge for the bank.

Political and media pressure to start cutting rates is building. And in any case, the Bank itself has started to lean into the idea of an imminent rate cut. Governor Andrew Bailey has signalled he’s comfortable with markets pricing roughly three rate cuts this year, implying he’s encouraged by recent inflation data. And while the Bank’s recent statements have formally said that “restrictive” policy is needed for an “extended period”, the BoE is now making clear that this statement can still be true even if rates start to be cut.

Admittedly, the committee’s hawks – Catherine Mann and Jonathan Haskel – who were still voting for rate hikes until recently- appear much less convinced. But the truth is that neither’s vote is likely to decide the timing of the first move. History tells us that when the committee changes tack, the so-called internal members, which include the Governor and his deputies, tend to change their vote simultaneously. In other words, we could quite easily see an 8-1 vote in favour of ‘no change’ in May but a 6-3 or 7-2 vote in favour of a rate cut in June.

The upshot is that a rate cut is getting closer. Markets are pricing a 20% chance of a cut in May and 75% in June, and crucially, investors no longer expect the BoE to be an outlier relative to the US Federal Reserve.

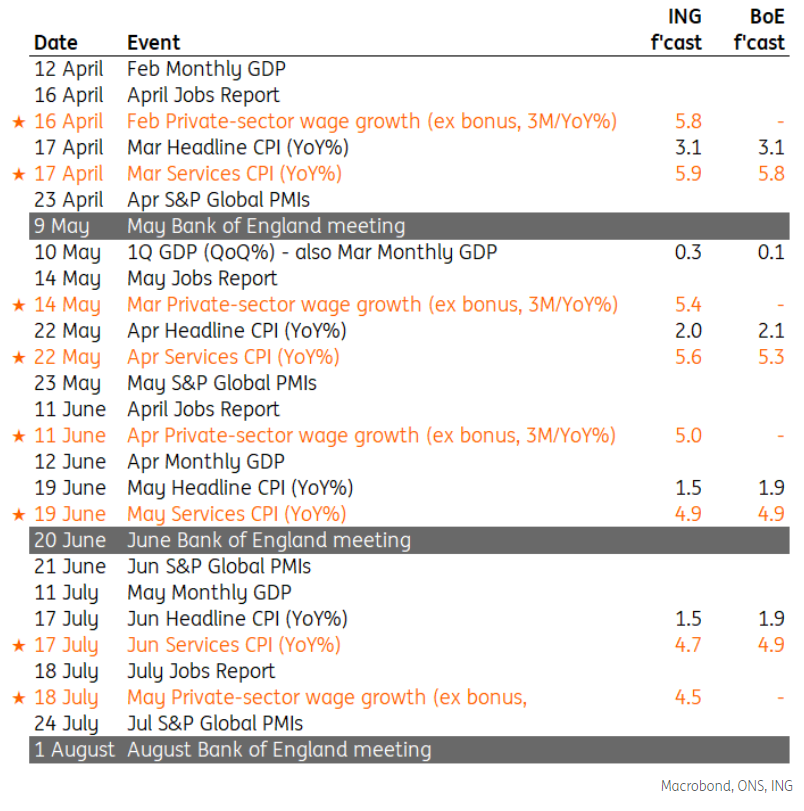

We agree with investors that a May cut is unlikely, despite Bailey’s recent comments being written up as opening the door to a move next month. The table below shows that only one set of inflation and wage data is due before the early May meeting, and neither release is likely to tell the Bank much more than it knew before.

A June rate cut has become more likely but isn't guaranteed

We also agree that a June rate cut is getting more likely, though we think it’s still far from guaranteed. For now, our base case is August; it’ll come down to three things:

Firstly – and most importantly – services inflation. The single most important data point before June’s meeting is the April inflation release on 22 May. We've written a lot about April, seeing many service-sector prices subjected to annual contractual price hikes, often directly linked to previous rates of headline CPI. A back-of-the-envelope estimate suggests roughly 40% of the services basket is affected by this phenomenon, and both April 2022 and 2023 saw high month-on-month price rises, even after we adjust the data for seasonality.

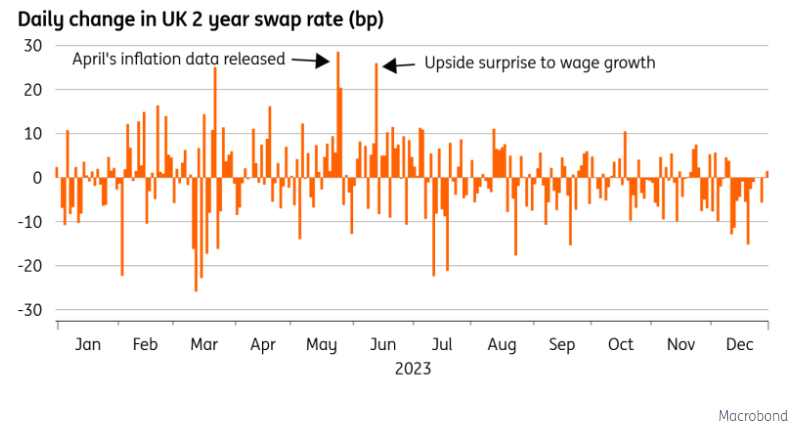

Last April’s blowout services CPI figure drove the biggest daily change in UK two-year swap rates of 2023, and the risk is this year’s release is a market mover too. It’s true that lower headline inflation rates should mean more subdued April price hikes than last year and, therefore, lower year-on-year rates of services CPI. But we think services inflation will fall more slowly than the Bank of England is forecasting in the near term.

That’s the main reason we’re still a bit reticent to move forward our BoE rate cut call from August to June. The recent experience in the US, where data has proven stickier than expected, is a cautionary tale for investors when thinking about a June rate cut in the UK.

Wage growth is also key

After inflation, the second thing to watch is private-sector wage growth, particularly those which include April, due on 11 June. That data will give a sense of the impact of the recent near-10% National Living Wage increase. There are reasons to think the macro impact won’t be huge, partly because the share of workers on NLW is relatively low but also because wage growth for lower-paid groups has been running at annualised rates in excess of 10%, even without the government’s intervention.

However, extra data will also help assess whether the recent improvement in weekly earnings growth can be sustained. Haskel, one of the BoE’s hawks, has suggested that widespread cost-of-living payments in late 2022/2023 were wrongly accounted for as permanent increases in salaries. Thus, the recent downtrend in wage growth is a symptom of measurement problems rather than a genuine easing of pay pressures. By the June meeting, the Bank will have a better idea of whether that’s the case.

Finally, there’s clearly a risk that the Bank uses the May meeting to effectively tell us it’ll cut in June. The BoE is generally much more reticent than other central banks to explicitly send these kinds of signals. But further changes to the forward guidance, such as watering down the language on “restrictive” rates, would amount to the same thing.

We're sticking to our base case - for now

In short, we’re inclined to stick to our base case of an August rate cut, though it’s become a closer call since recent BoE comments. If the services inflation data is more benign than we expect, wage growth continues to trend lower and/or the Bank itself drops heavy hints at its May meeting, then a June rate cut could easily materialise – particularly if the likes of the Fed and ECB have done the same thing.