By Tom Perry and Laila Bassam

BEIRUT (Reuters) - As the United States and Iran negotiate the final stages of a nuclear deal, they are still oceans apart on another area of conflict: the future of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

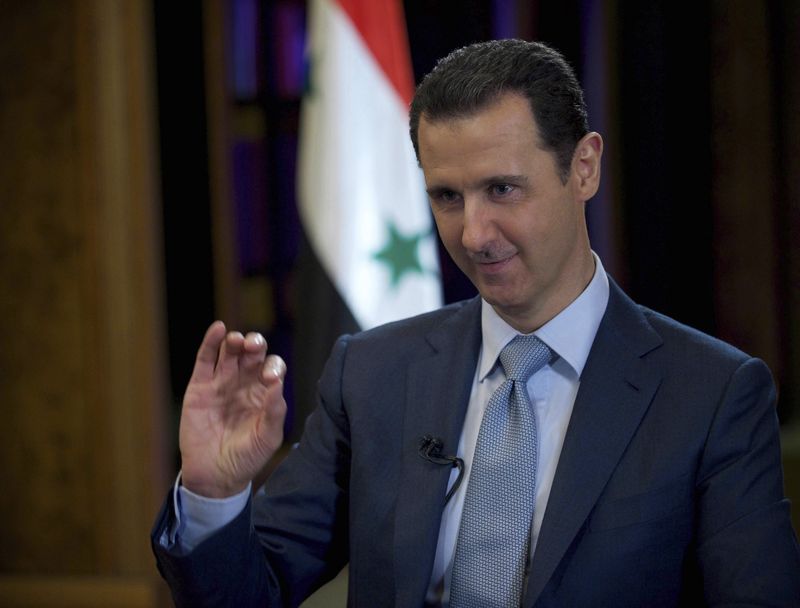

Assad seems more likely to survive the Syrian crisis than at any point since it began four years ago. Iran's support is as solid as ever to its confident-looking ally in Damascus.

The days when Assad was largely absent from view and his mere appearance was news have given way to almost daily reports on his activities; recent visitors included four French members of parliament who defied their government's policy to see him.

The civil war has no doubt left Assad weakened, but he is stronger than the groups fighting to topple him. Powerful states still want to see him gone, but they have shown less resolve than allies who are standing by him.

As the crisis approaches its fourth anniversary, the demand for Assad's departure is heard less often from his Western foes. Their attention has instead switched to fighting Islamic State, an enemy they share with him.

While the United States and his Arab enemies bomb the jihadists in the north and east, Assad and his allies have launched a major offensive against mainstream rebels and Islamists in an area of greater importance to them, the southern border zone near Israel and Jordan. In Damascus, observers close to the government see this as the start of a phase that will end the conflict on Assad's terms.

Iranian-backed Lebanese group Hezbollah is backing the southern campaign and Iranian advisers are in the field - mirroring the situation in Iraq, where they are helping to oversee operations against Islamic State, said a senior Middle Eastern official familiar with Syrian and Iranian policy.

"The battle in Syria is still a very long one, but without existential threats for the government," he said.

The continued support for Assad has defied the hopes of Western governments that it might wane as a slump in oil prices makes it more expensive for Tehran to prop up the devastated Syrian economy, or as Iran negotiates with world powers for a deal over its disputed nuclear programme.

"The Iranians still view Assad as the top man," said the official, speaking on condition of anonymity because his assessment was based on private conversations. "He is the focal point of their relationship with Syria."

Russia, too, shows no sign of abandoning a leader who finds himself at the centre of two struggles: between Moscow and the West, and between Sunni Muslim Saudi Arabia and Shi'ite Islamist Iran.

A senior U.S. State Department official said support provided to Assad by backers including Iran had allowed him to avoid a negotiated end to the conflict, and described Iran's role as "destructive".

"We continue to coordinate with the international community on ways to limit Iran's efforts to resupply the Assad regime with the means to perpetuate its brutality against the Syrian people," the official said.

MEDIA OFFENSIVE

A confident-looking Assad has meanwhile embarked on a public diplomacy campaign, giving five interviews since December. Three were with organisations based in the Western states most opposed to his rule: the United States, France and Britain.

But it seems unlikely to end Assad's pariah status in the West and among his Arab enemies. U.N. reports detail the army's use of indiscriminate violence, including barrel bombs. U.S. officials often say he is a leader who has gassed his own people, a charge the government denies.

The war has killed some 200,000 people and displaced close to half the population, according to U.N. figures. Damascus accuses its Western and Gulf Arab opponents of seeking to destroy the country by providing aid to an insurgency now dominated by jihadists who pose a threat to the West.

The state's territorial grip is much reduced, but it still controls the most populous areas. The rest is divided among jihadists, mainstream rebels and a Kurdish militia that has emerged as an important partner in the U.S.-led battle with IS.

The overstretched military and allied militia have suffered big losses this past year. Even with its air force, the army has been unable to finish off insurgents on important frontlines such as Aleppo.

Insurgents repulsed a recent offensive to encircle rebel-held parts of Aleppo, killing at least 150 soldiers and pro-government militiamen, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a British-based group that monitors the conflict.

But neither Aleppo nor Islamic State-held parts of the country matter to Assad as much as the corridor stretching north from Damascus through Homs and Hama and then west to the coast.

Assuming the army and allied militia win, the battle against the insurgents in the southern border zone would eliminate one o

By Tom Perry and Laila Bassam

BEIRUT (Reuters) - As the United States and Iran negotiate the final stages of a nuclear deal, they are still oceans apart on another area of conflict: the future of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Assad seems more likely to survive the Syrian crisis than at any point since it began four years ago. Iran's support is as solid as ever to its confident-looking ally in Damascus.

The days when Assad was largely absent from view and his mere appearance was news have given way to almost daily reports on his activities; recent visitors included four French members of parliament who defied their government's policy to see him.

The civil war has no doubt left Assad weakened, but he is stronger than the groups fighting to topple him. Powerful states still want to see him gone, but they have shown less resolve than allies who are standing by him.

As the crisis approaches its fourth anniversary, the demand for Assad's departure is heard less often from his Western foes. Their attention has instead switched to fighting Islamic State, an enemy they share with him.

While the United States and his Arab enemies bomb the jihadists in the north and east, Assad and his allies have launched a major offensive against mainstream rebels and Islamists in an area of greater importance to them, the southern border zone near Israel and Jordan. In Damascus, observers close to the government see this as the start of a phase that will end the conflict on Assad's terms.

Iranian-backed Lebanese group Hezbollah is backing the southern campaign and Iranian advisers are in the field - mirroring the situation in Iraq, where they are helping to oversee operations against Islamic State, said a senior Middle Eastern official familiar with Syrian and Iranian policy.

"The battle in Syria is still a very long one, but without existential threats for the government," he said.

The continued support for Assad has defied the hopes of Western governments that it might wane as a slump in oil prices makes it more expensive for Tehran to prop up the devastated Syrian economy, or as Iran negotiates with world powers for a deal over its disputed nuclear programme.

"The Iranians still view Assad as the top man," said the official, speaking on condition of anonymity because his assessment was based on private conversations. "He is the focal point of their relationship with Syria."

Russia, too, shows no sign of abandoning a leader who finds himself at the centre of two struggles: between Moscow and the West, and between Sunni Muslim Saudi Arabia and Shi'ite Islamist Iran.

A senior U.S. State Department official said support provided to Assad by backers including Iran had allowed him to avoid a negotiated end to the conflict, and described Iran's role as "destructive".

"We continue to coordinate with the international community on ways to limit Iran's efforts to resupply the Assad regime with the means to perpetuate its brutality against the Syrian people," the official said.

MEDIA OFFENSIVE

A confident-looking Assad has meanwhile embarked on a public diplomacy campaign, giving five interviews since December. Three were with organisations based in the Western states most opposed to his rule: the United States, France and Britain.

But it seems unlikely to end Assad's pariah status in the West and among his Arab enemies. U.N. reports detail the army's use of indiscriminate violence, including barrel bombs. U.S. officials often say he is a leader who has gassed his own people, a charge the government denies.

The war has killed some 200,000 people and displaced close to half the population, according to U.N. figures. Damascus accuses its Western and Gulf Arab opponents of seeking to destroy the country by providing aid to an insurgency now dominated by jihadists who pose a threat to the West.

The state's territorial grip is much reduced, but it still controls the most populous areas. The rest is divided among jihadists, mainstream rebels and a Kurdish militia that has emerged as an important partner in the U.S.-led battle with IS.

The overstretched military and allied militia have suffered big losses this past year. Even with its air force, the army has been unable to finish off insurgents on important frontlines such as Aleppo.

Insurgents repulsed a recent offensive to encircle rebel-held parts of Aleppo, killing at least 150 soldiers and pro-government militiamen, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a British-based group that monitors the conflict.

But neither Aleppo nor Islamic State-held parts of the country matter to Assad as much as the corridor stretching north from Damascus through Homs and Hama and then west to the coast.

Assuming the army and allied militia win, the battle against the insurgents in the southern border zone would eliminate one of the last big threats to Assad.

It would prevent his foreign enemies from funnelling military aid to rebels via Jordan, and enable Assad to preserve a frontier with Israel. That is a big consideration for Damascus, Hezbollah and Iran, which have all sought to build popular legitimacy around the struggle with Israel.

"This is considered a qualitative shift in the war we are waging," said Damascus-based strategic analyst Selim Harba.

Mohamed Kanaisi, editor of the state-run Baath newspaper, said: "Military progress must lead to a political solution. The other forces will be forced to deal with the Syrian government."

VICTORY OR COMPROMISE?

The idea of an outright military victory runs counter to the widely held view in the West that the war can only end with a compromise. Diplomacy aimed at promoting such an outcome has gone nowhere since peace talks collapsed a year ago.

Western officials are seeking ways to prop up what is left of the mainstream opposition so it can go to future negotiations on a stronger footing. The United States is planning to train and equip rebels to fight Islamic State.

But the scale and focus of the programme seem unlikely to change the power balance quickly, if at all.

Assad appears to be betting that the U.S.-led campaign against Islamic State will force Washington to engage with him, particularly as Iraqi forces prepare to take back Mosul in northern Iraq. An effective campaign against IS in Iraq can only be waged with cross-border cooperation that would stop the jihadists from regrouping in Syria.

Assad says he is already being kept abreast of the U.S.-led air strikes in Syria via third parties including Iraq.

Western officials dismiss the idea of rehabilitating him as a partner in the fight against IS: even if they staged a U-turn, Assad would be incapable of winning back all of Syria, they say.

"You can't get away from the idea that a Syria with Assad at the helm is never going to be a united one. He cannot reunite Syria. If we cave in on that it will not fix the problem," said one Western official.

The senior U.S. State Department official said: "We maintain our firm belief that Assad has lost all legitimacy and must go. There can never be a stable, inclusive Syria under his leadership."