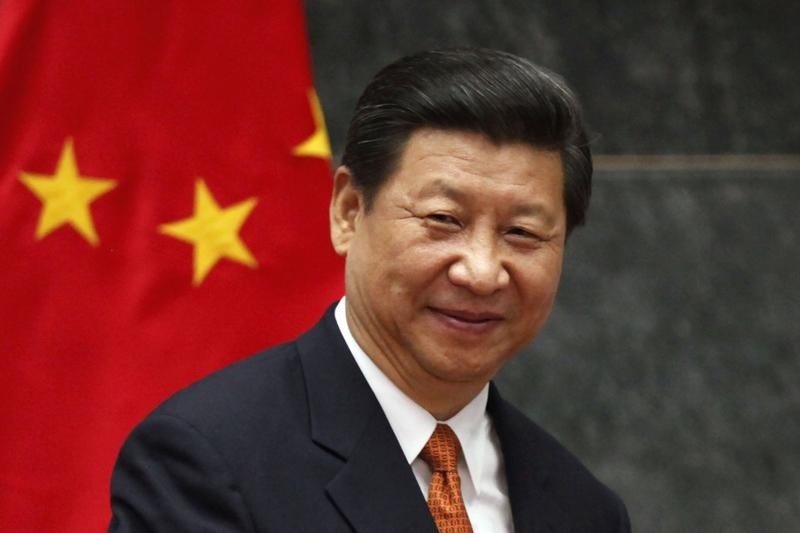

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As president-for-life, Xi Jinping is neither bound by rules nor limited by rivals. He has upended a careful political balance by concentrating power in his own hands, and overturned a cautious approach to foreign policy, while throwing in jail anyone he views as a threat. China’s most dominant leader since Mao Zedong now has 90 days to head off an all-out trade war with the U.S. provoked, in part, by his own mercantilist policies. Can anybody convince him to make a U-turn?

Strong-willed politicians in democracies, let alone authoritarians in one-party states like China, have trouble executing this maneuver. Former U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously proclaimed “the lady’s not for turning” when pressed to shift course on her harsh economic policies. Unlike Thatcher, Xi doesn’t have an electorate, or a free press, to question his judgment. He’s the object of a rising personality cult. Recently, the People’s Daily mentioned his name 103 times in one edition – 45 times on the front page.

But while an about-face may be too much to expect from the Chinese strongman, there are three reasons to think he might be persuaded to tack in a different direction.

First, China has come out worse than the U.S. from their tariff spat – the opposite of what many economists predicted at the outset – and it is exacerbating grave economic problems for which Xi has no easy answers: slowing growth, sinking private investment, rising debt and real estate bubbles. Analysts at JPMorgan Chase & Co (NYSE:JPM). reckon China could lose 5.5 million jobs in an all-out trade war.

Having said that Xi has no rivals, that doesn’t mean he faces no opposition. He has made enemies galore – enough to prompt him to make a personal call for “unconditional loyalty” from party members earlier this year – and they are waiting to pounce on his mistakes. There are clear signs that the elites are uneasy about his imperial style. In a leaked speech widely interpreted as a swipe at Xi, Deng Xiaoping’s eldest son, Deng Pufang, cautioned against “overestimating oneself and behaving recklessly.” None of this suggests that Xi’s position is under threat, but it raises the political risks to him if the trade war gets out of hand and triggers an economic crisis.

If the question “Who lost America?” ever comes up, Xi will find himself very much on the defensive. His administration misread Trump and misjudged the American mood. In sum, domestic politics could give him a second incentive to compromise.

The third is more obvious: Nobody loses more than China if the global trading system blows up, unraveling supply chains and splitting the world into competing economic spheres. Whatever happens in the next 90 days, the U.S. will try to ring-fence certain advanced technologies to keep them out of Chinese hands on security grounds. If a full-on trade war turns into an unrestricted tech Cold War, China will again suffer more, although of course everybody gets hurt. While its innovation ecosystems are flourishing, and money is pouring into AI startups, China can’t yet do without U.S. technology as it upgrades its industrial base to avoid the dreaded “middle-income trap.”

Let’s be realistic: China won’t remake its state-planned economy, or give up its high-tech leadership ambitions to suit Trump. For Xi, that would be tantamount to abandoning the right to development and dreams of a wealthier society. But there is scope for a deal – albeit a limited one – if indeed that’s what Trump actually wants rather than Cold War containment, in which case Xi has little reason to cede ground at all. The fact that Trump’s negotiating team is split between ideologically driven hawks, and economic pragmatists, makes it hard for Xi to read his intentions.

Much of what the U.S. is pushing for – greater market access; a level playing field with state enterprises; an end to theft and forced transfers of technology; more respect for intellectual property – is in line with China’s own reform needs. Xi himself called for a “ decisive role” for markets before doubling-down on state enterprises and top-down party control.

One indication that Xi doesn’t want an escalation is that state media are playing down the trade war. Another is that China hasn’t retaliated against U.S. companies. The reason isn’t just that Xi is worried about whipping up anti-U.S. nationalism in a way that could box him in; he is surely anxious, too, about public confidence. The older generation might be ready to tighten their belts — or, to use a Chinese phrase, “eat bitterness” — if that’s what an all-out trade war entails, but millennials are a softer bunch, and they have never experienced an economic setback. Many investors are gripped by an ominous sense that this trade dispute could lead China off a cliff: the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index of stocks is down about 20 percent this year, and the currency has fallen more than 5 percent against the dollar.

Set against all this, however, is the notorious reluctance of strongmen to admit mistakes and self-correct. The American political scientist Francis Fukuyama argues that China, having discarded presidential term limits, faces a recurrence of its age-old “Bad Emperor” problem that places the country at the mercy of a single individual – fine when an enlightened ruler comes along, disastrous when a despot appears. It’s too early to say where Xi sits on that spectrum. His readiness to reignite domestic reform, and seek an off-ramp in the trade dispute, will be a strong clue.