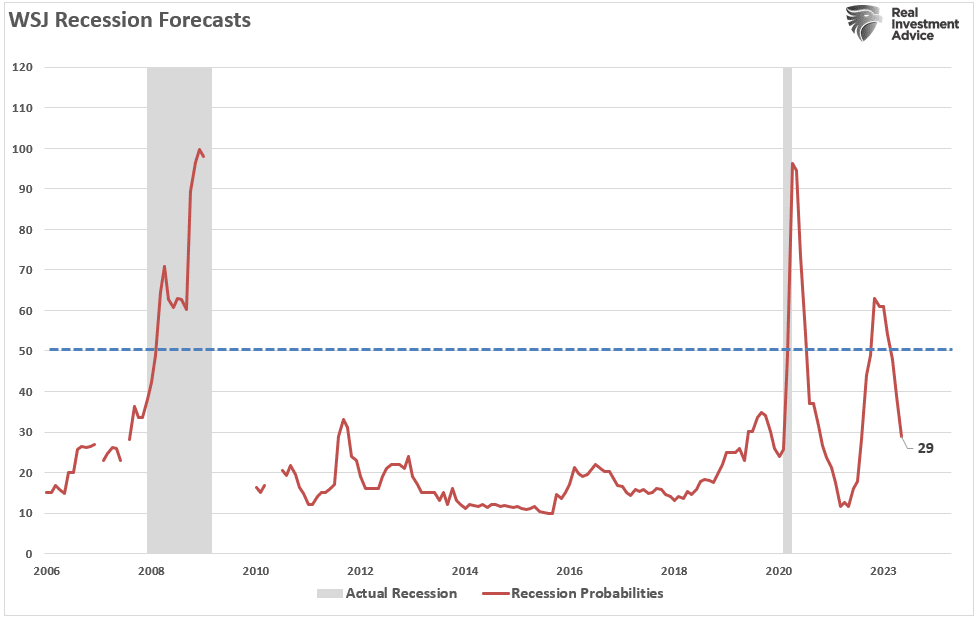

As we discussed recently, Wall Street economists increasingly believe the risk of recession has fallen sharply. To wit:

“Economists don’t think the economy will get even close to a recession. In January, they, on average, forecast sub-1% growth in each of the first three quarters of this year. Now, they expect growth to bottom out this year at an inflation-adjusted 1.4% in the third quarter.” – WSJ

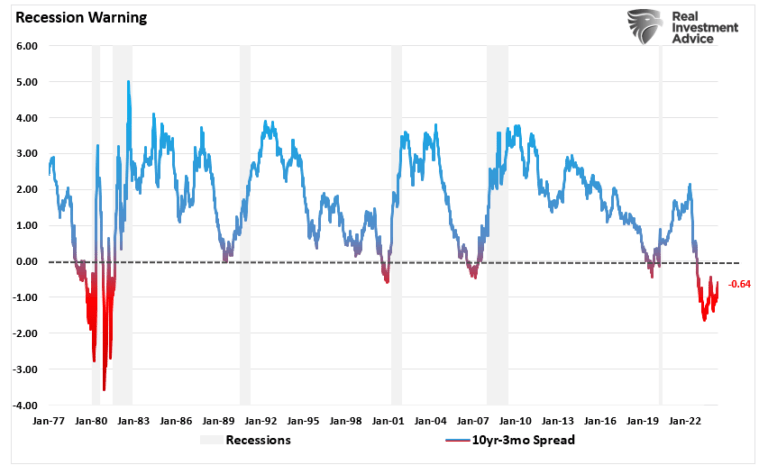

Of course, this outlook seems contradictory to numerous indicators with a long history of preceding recessionary onsets, such as yield curve inversions. As shown, we currently have the longest, consistent period in history where the yield spread between the 10-year Treasury bond and the 3-Month Treasury bill is inverted. Yet, no recession has manifested itself this time.

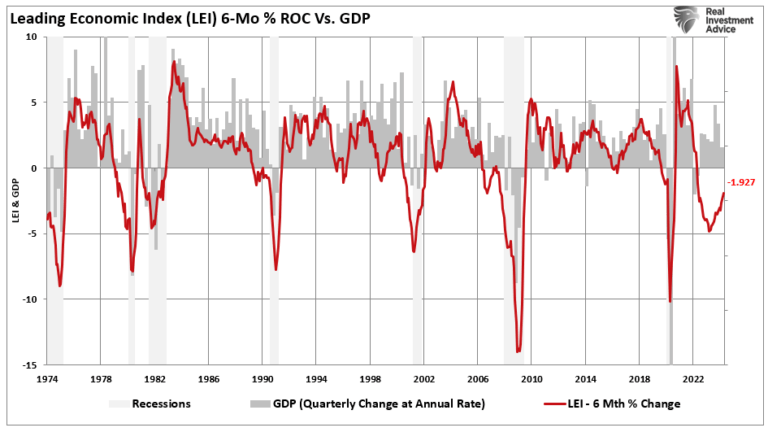

Another historically reliable recession indicator is the 6-month rate of change of the Leading Economic Index. As with yield curve inversion, the current depth and duration of the LEI’s negative readings have always coincided with a recession. But again, the U.S. has avoided such an outcome.

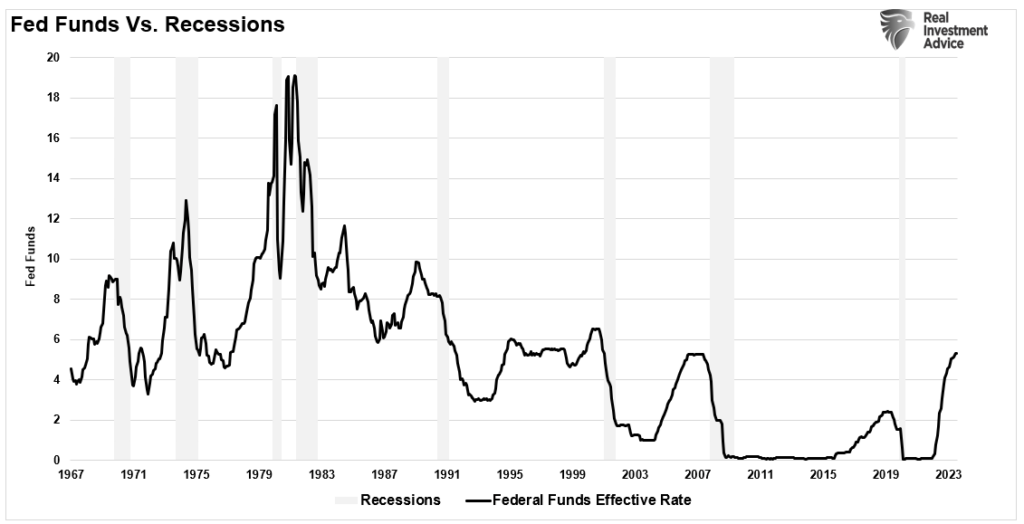

Of course, the Federal Reserve’s tightening of monetary policy through one of its more aggressive rate-hiking campaigns also failed to push the economy into a recession.

Given that the economy has continued to defy recession expectations, it is understandable that economists have “given up” anticipating one.

But is the risk of recession gone?

The Risk Of Recession Isn’t Zero

There is a very funny meme circulating on social media. Yes, cute, cuddly animals seem safe, but “the risk of them murdering you is low but never zero.”

Such seems like an appropriate meme, given that the economy’s recession risk may be low currently, but it isn’t zero.

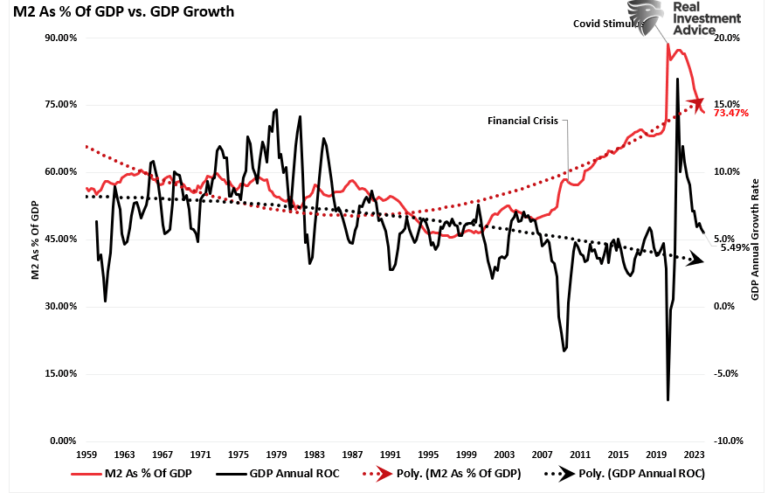

As discussed previously, one of the primary reasons why the economy has defied the recessionary drag from higher borrowing costs has been the ample supply of fiscal support through previously passed spending bills such as the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPs Act. When combined with stimulus checks, tax credits, and moratoriums on various debt payments like rent and student loans, the amount of monetary support for consumption supported economic growth as the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy.

What is crucial to understand is that the surge in monetary support acted as an “adrenaline” boost to the economy. Yes, many economic data series suggest the risk of recession is elevated. However, the surge of monetary injections sent the economy into overdrive, as evidenced by economic growth in 2021.

The crucial point to understand, and what eludes most economists, is that the economy slows as that “adrenaline” boost fades. Had the economy been growing at 5% nominal, as in 2019, the decline from the post-pandemic peak would already register a recession.

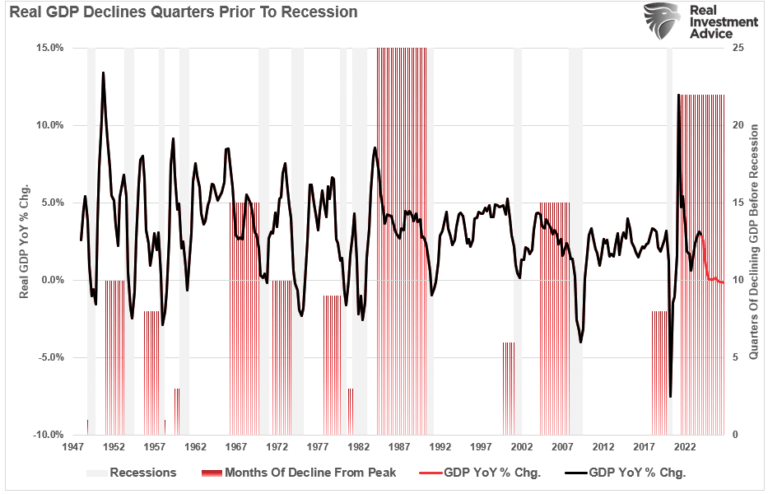

However, given that nominal growth neared 18%, it will take much longer than normal for growth to revert below zero. To show this, we looked at the number of quarters between peak economic activity and the entrance into a recession. Using that historical analysis, we can estimate the reversion of economic growth into a recession could take roughly 22 quarters. Such would time the next recession in late 2025 to mid-2026.

Many things could certainly happen to lengthen or shorten that estimated time frame. However, the importance is that a reversal of growth from elevated economic growth rates can take much longer than normal. Another similar period was the 25 quarters of slowing economic growth before the 1991 recession.

For investors, while consensus estimates of economists put the risk of recession very low, it is not zero.

Economic Data To Watch

Given the long lag between recessionary indicators and economic recession, it is unsurprising economists gave up anticipating a recession. However, while the recession has not happened yet, it does not mean that it still can’t. We should pay special attention to data historically correlated to economic growth.

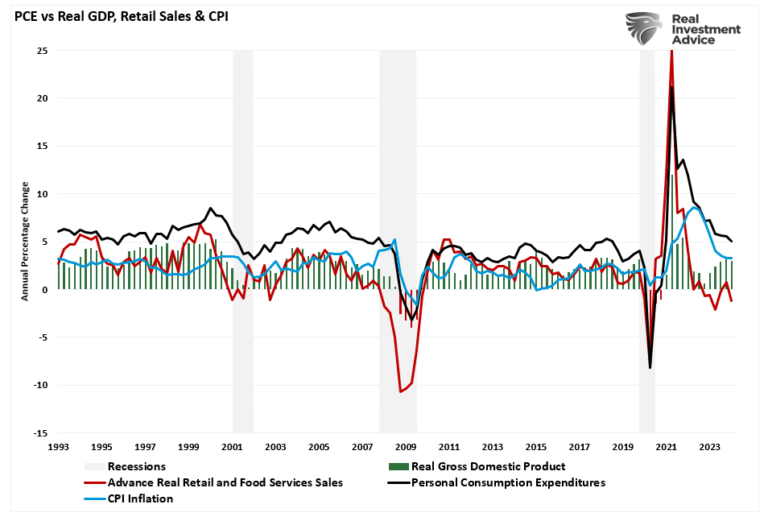

For example, real retail sales have weakened materially since the peak of economic activity in 2021. As shown, retail sales make up roughly 40% of Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE). Therefore, it is unsurprising that retail sales precede PCE changes.

The importance of that lead is that PCE comprises nearly 70% of the GDP calculation. Therefore, as consumer demand slows, the economy slows, and inflation falls. Real retail sales are now negative as consumers run out of excess savings, likely slowing economic growth further in the quarters ahead.

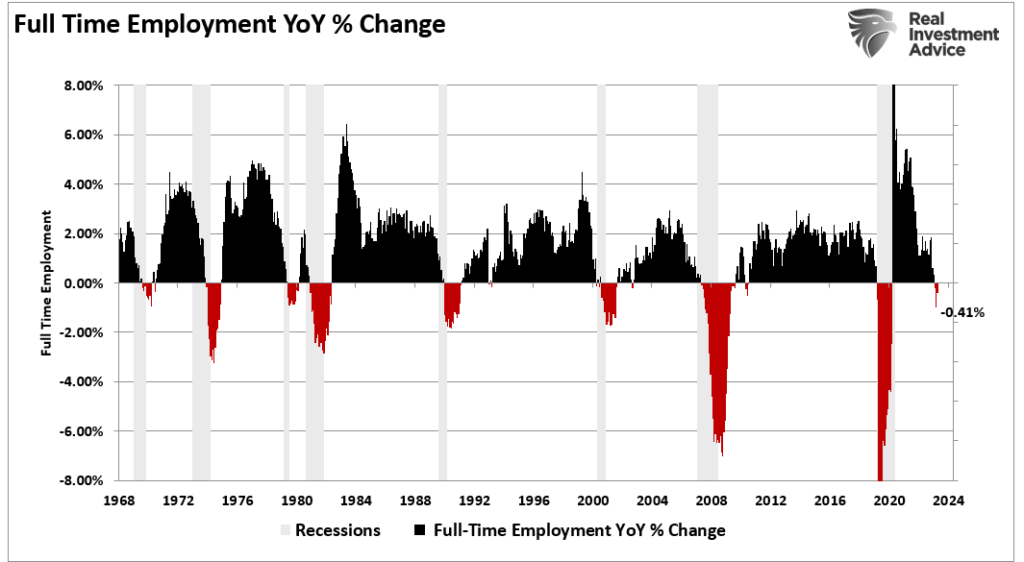

Of course, without employment, it is hard to increase economic consumption further. Notably, while we count part-time employment, those jobs do not provide the wages and benefits of full-time employment to support a family. Unsurprisingly, a key leading indicator to every previous recession has been a reversal of full-time employment.

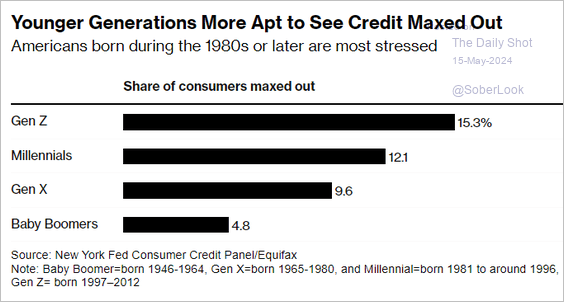

While it is certainly possible that the economy could avoid a recession given additional monetary or fiscal support, government and business investment comprise a much smaller contribution to GDP than consumer spending. As notedbefore, with consumers strangled between declining wage growth and higher living costs, the ability to fuel the difference with debt is becoming increasingly challenging.

“The consequence of that lack of income growth is that they are the first to run into the limits of taking on additional debt.”

Pay attention to the economic data in the future. While it may take much longer than many expect, we suspect the risk of recession is likely greater than zero.