- The chancellor is poised to get extra wiggle room

- "Headroom" is higher, but still limited

- Medium-term spending plans look challenging

- Modest tax cuts possible, but it wouldn't move the needle much for the BoE

The chancellor is poised to get extra wiggle room

UK Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is likely to be gifted with a rare bit of good news as he gears up for his Autumn Statement on 22 November. Not only has borrowing come in £20bn lower than forecast so far this fiscal year, but new projections from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) are likely to show that he has a little more wiggle room to play with, whilst still meeting his main fiscal goal of lowering debt as a share of GDP within five years.

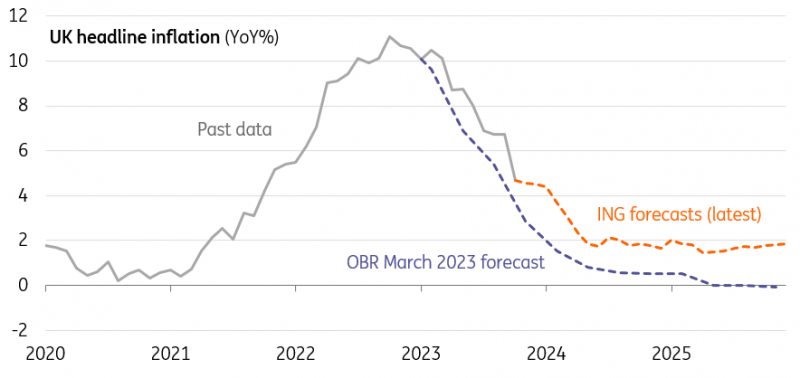

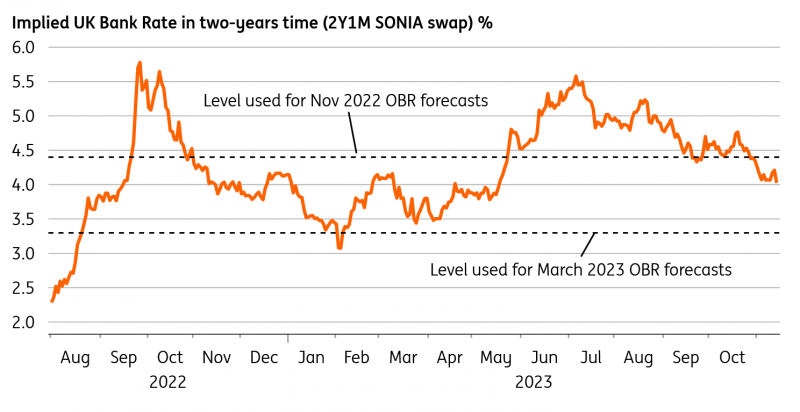

It’s true that markets expect Bank Rate to be roughly one percentage point higher than when the OBR last produced forecasts in March, which is likely to push up the forecast for debt interest (net) by roughly £18bn in 2027/8 by our estimates. But that has, of course, gone hand in hand with higher inflation.

That translates into higher nominal spending on things like welfare, though the government is reportedly looking to temper that increase by uprating welfare benefits by October's (lower) inflation reading, rather than using September's (higher) reading as is more typical. But higher inflation also means more money coming in for the Treasury, and that’s what’s likely to dominate the new OBR projections.

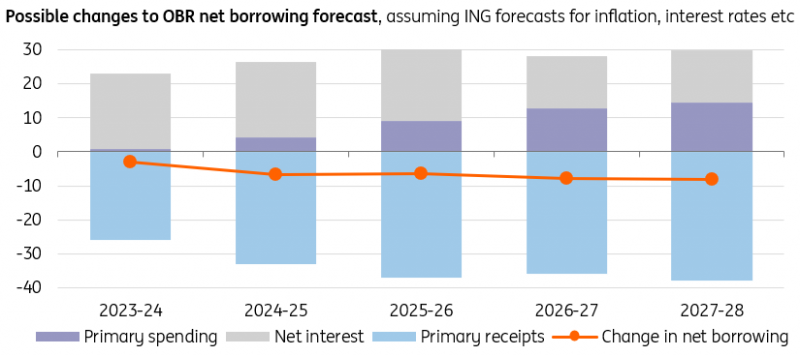

When we wrap all of that together and plug our own inflation/wage forecasts into the OBR’s “ready reckoner” model, those extra revenues outweigh the negative impact of higher interest rates and inflation on spending.

Inflation has come in higher than the OBR forecast in March...

...but interest rates are expected to be higher too

"Headroom" is higher, but still limited

Our rough estimates suggest the chancellor will be landed with roughly £15bn in “headroom” against his fiscal targets, which is an increase from the £6.5bn available back in March. That figure is based on market rate expectations, and we reckon that figure would rise by a further £6-7bn if we’re right that the Bank of England cuts Bank Rate more aggressively than markets expect over the next couple of years.

Whichever way you cut it though, that’s still not a huge margin to play with. Hunt’s predecessors, particularly those in post before Covid, typically built in larger headroom than the £15bn likely to be available to the Treasury next week. It means he doesn’t have much to play with ahead of an anticipated election next year, which we’re assuming comes in October 2024 (though formally it can happen at any point before the end of January 2025).

That’s even more true when you consider that some of the budgetary assumptions underpinning the forecasts described above look unrealistic. Hunt managed to win back markets this time last year with an Autumn Statement that combined some near-term stimulus with longer-term austerity, via an even mix of tighter tax and spending policies. Those included a 15% cut to public sector net investment in nominal terms annually by 2027/28 - or put another way, it goes from 2.9% of GDP to 2% over that same time frame.

Higher revenues from inflation trump debt interest increases, according to OBR model

Estimates use March 2023 OBR "ready reckoner" model, and we've adjusted it using our latest inflation and wage forecasts. Most other variables are unchanged, for simplicity, so estimates shouldn't be taken as precise

Medium-term spending plans look challenging

One particular challenge with this is that it appears inconsistent with the government’s net zero commitments. The pathway that the government has committed to will almost certainly require heavier public investment than we’ve seen so far (particularly in buildings). The opposition Labour Party has pledged to increase investment in this area, and the Institute for Fiscal Studies reckons this would limit the fall in net investment to 2.5% of GDP by 2027/8.

The OBR’s forecasts are also based on government plans to limit day-to-day spending in government departments, such that in real terms, per capita expenditure will fall over the next couple of years. The scale of those real-terms cuts will be more aggressive in departments where budgets are not protected, and these could be challenging to achieve in practice.

Finally, the plans for later this decade also assume that some of the government’s flagship tax policies are only temporary. That includes the government’s capital allowances, which allow firms to offset certain investments against their tax bill, and are slated to end after three years. Extending that looks inevitable, and would likely cost £9-10bn/year, eating up more than half of the chancellor’s already tight “headroom”. The OBR’s forecasts also assume that a 5p/litre cut to fuel duty is phased out, and that this is uprated by inflation in future years – something that hasn’t happened since 2011 despite repeated plans to the contrary.

Modest tax cuts possible, but it wouldn't move the needle much for the BoE

Does all of this rule out a sizable cut to, for example, income tax ahead of the next election? Hunt shelved plans to cut the basic rate of income tax from 20% to 19% this time last year, with a saving of £6bn/year later this decade. It’s possible that these plans will be reheated in the spring ahead of the forthcoming election, and it’s likely that the chancellor will have the fiscal space to do so. But that’s likely to be as far as the government can go without making even deeper planned cuts elsewhere later this decade.

None of this would likely move the needle for the Bank of England. A tax cut of that magnitude, if it comes, is unlikely to make a decisive difference to next year’s growth outlook. More importantly, we think by the spring it will have become more evident that inflationary pressures are cooling, and by summer we think both services inflation and wage growth will be back to the 4% area. While still too high for the BoE’s liking, we think that would be sufficient to unlock rate cuts by August.