Global manufacturing contracted at the fastest rate in over a decade during February as the coronavirus disrupted supply chains and hit demand, according to PMI survey data. The downturn was led by a record slump in activity at China's factories, with the rest of the world stagnating. The answer as to whether production will revive or turn down in coming months will depend both on supply chains and demand.

Output, new orders and trade show biggest slumps since 2009

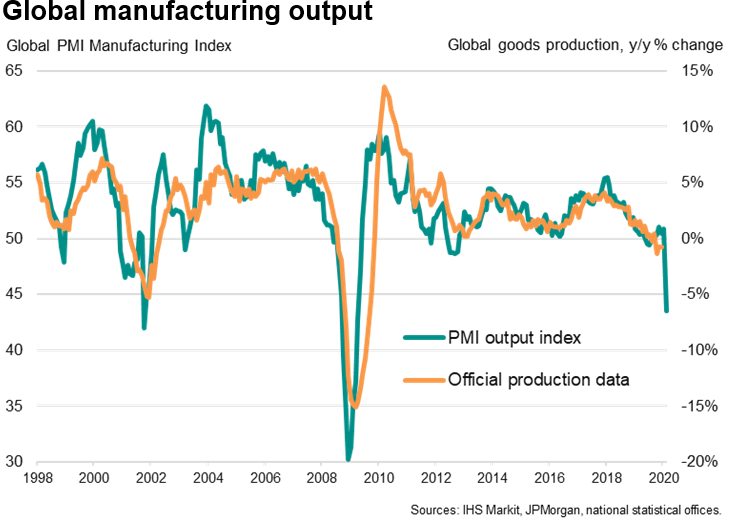

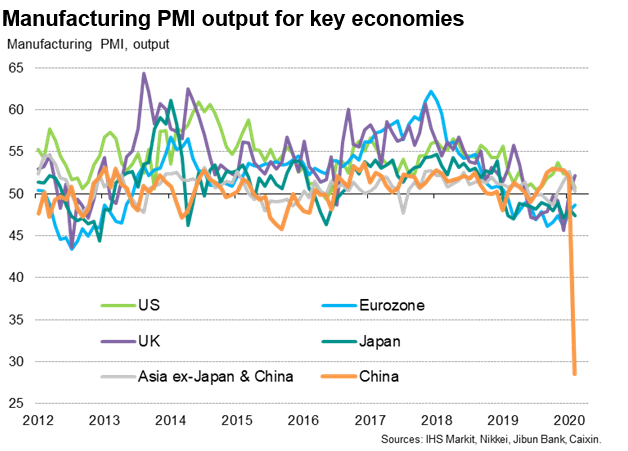

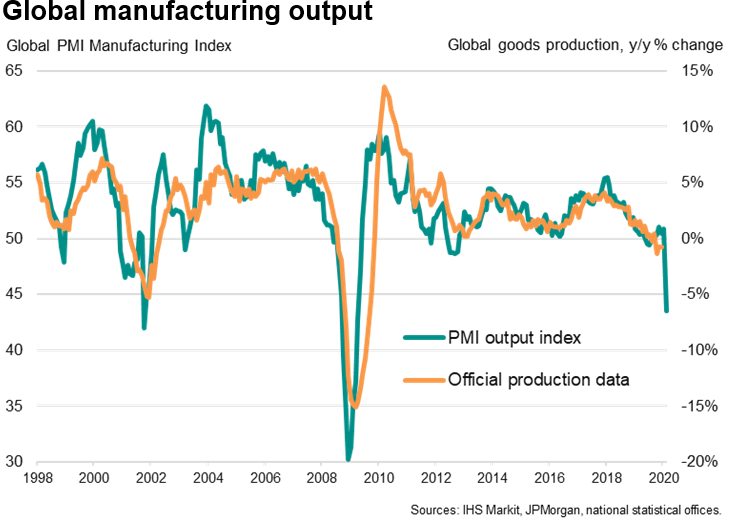

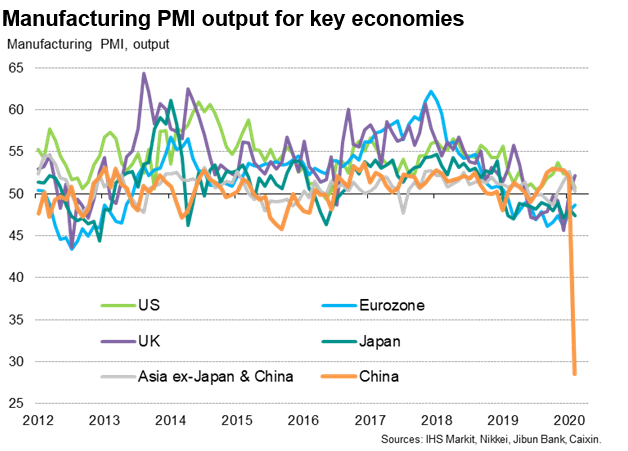

The JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM) Global Manufacturing PMI, compiled by IHS Markit from its surveys in 31 markets, fell 3.2 points from 50.4 in January to 47.2 in February, its lowest since May 2009 and signalled a renewed steep deterioration in the health of worldwide manufacturing.

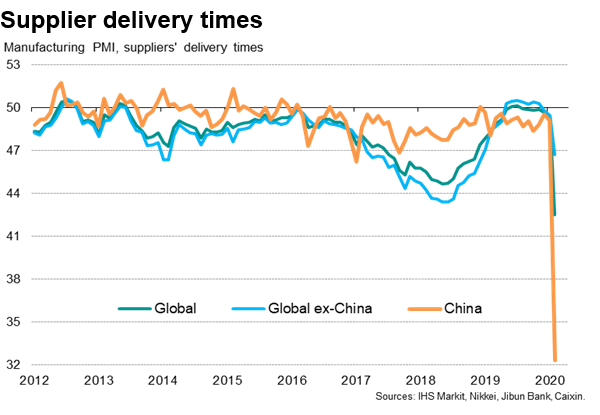

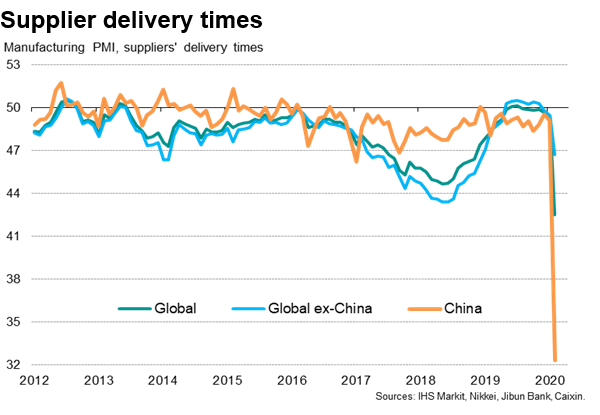

To get a better understanding of the true depth of the downturn we need to look at the PMI's sub-components. The PMI is a weighted average of five survey variables: new orders, output, employment, suppliers' delivery times and inventories of purchased inputs. Both output and new orders fell at even faster rates than the headline PMI, the latter having been buoyed to some degree by longer delivery times. Longer deliveries are normally a sign of a busier economy, and hence boost the PMI. However, at present, longer deliveries are almost entirely due to virus-related shutdowns, according to survey replies.

Looking at the current indices of output and demand, the monthly drop in worldwide factory production was the steepest since April 2009, the output index dropping some 7.3 points compared to January. The new orders index meanwhile slumped 5.6 points to also reach its lowest since April 2009, in part reflecting the largest slide in global exports for over ten years as demand for goods fell sharply.

Factory jobs were meanwhile cut globally at the fastest rate since August 2009 as companies scaled back production capacity in line with falling demand and the reduced supply of inputs.

Near-record delivery delays as coronavirus disrupts supply chains

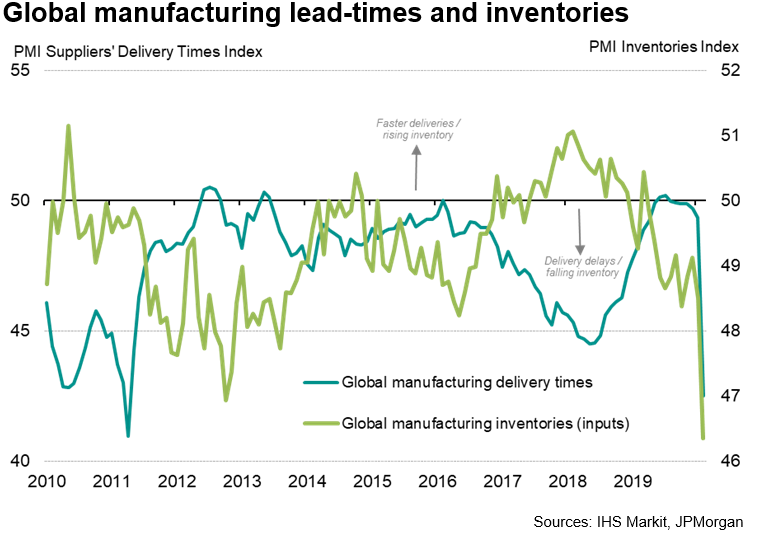

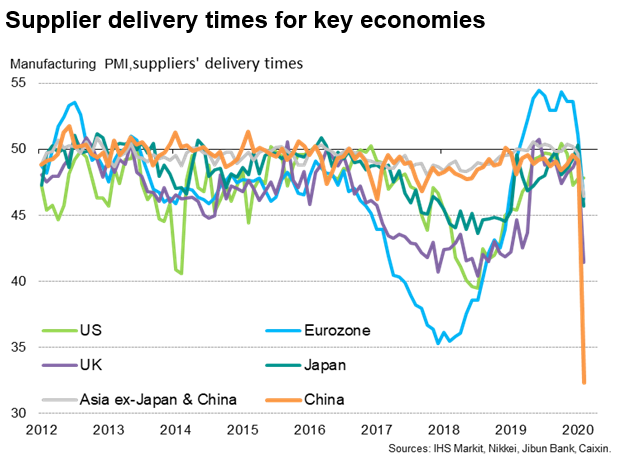

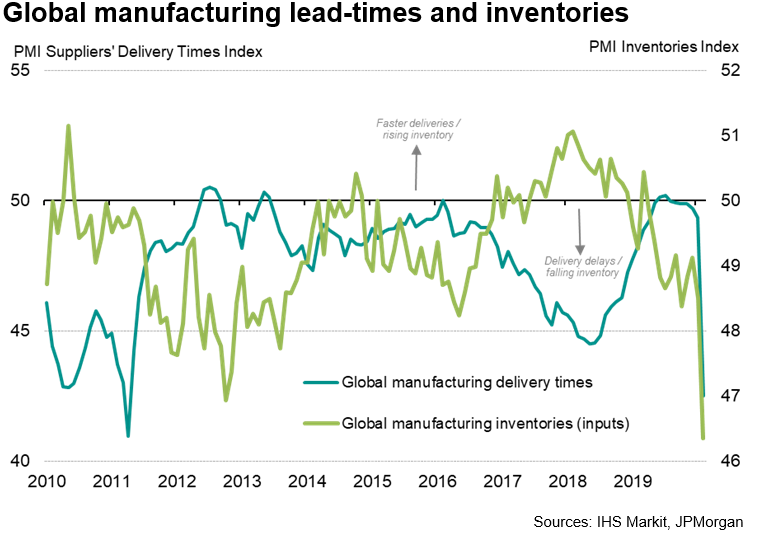

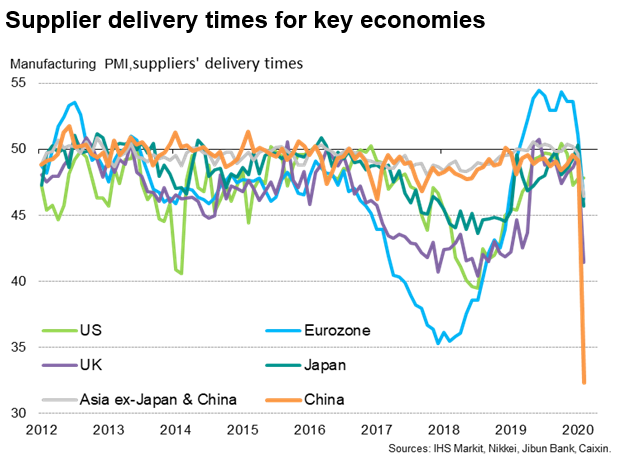

The extent of supply chain delays was reflected in the second-longest lengthening of suppliers' delivery times since global production growth boomed in 2004. The current lengthening was exceeded only by the delays seen in April 2011 after the Japanese earthquakes. Importantly, like 2011, the latest delivery times lengthening was due to a supply shock (rather than strong demand, as in 2004), linked by many companies to delays in the provision of inputs due to extended virus-related factory shutdowns in China.

Global inventory holdings of inputs fell to the greatest extent since November 2009 largely as a result of the supply limitations. Similarly, stock of finished goods fell to the sharpest degree for almost four years, reflecting constrained production in many companies.

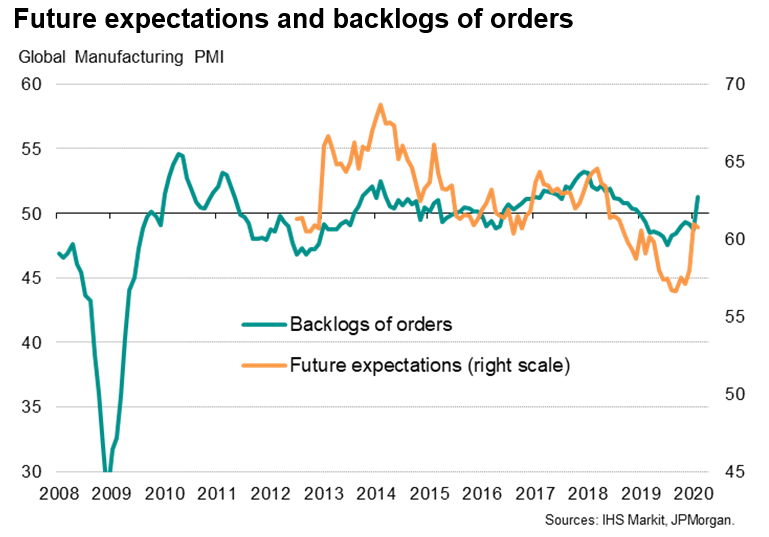

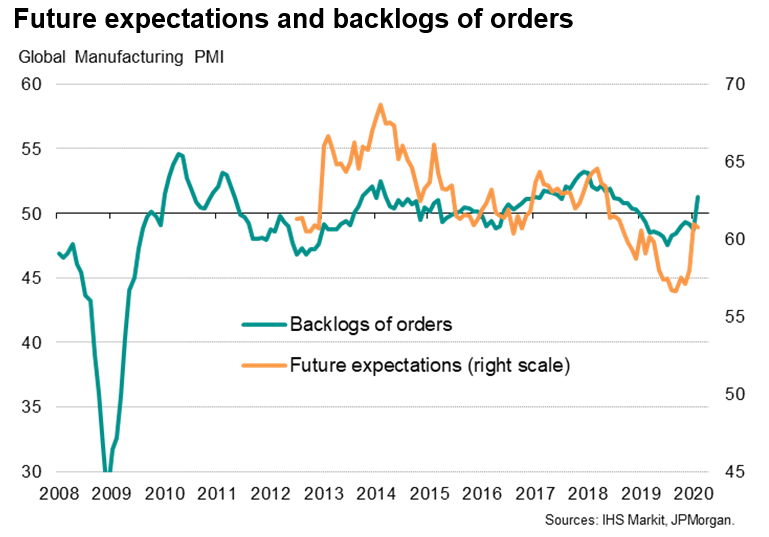

The constraints on production from limited supply availability led to a rise in backlogs of work for the first time since December 2018, with the accumulated volume of uncompleted orders rising to the greatest extent for just over one and a half years. This build-up clearly hints at a rebound in production as these backlogs can be fulfilled when new supplies of inputs can be sourced. Indeed, companies' expectations of their output growth over the coming year remained largely unchanged on the near-one-and-a-half year high seen in January. However, much will depend not just on the speed with which supply chains can return to normal, but also on whether demand takes a deeper and more long-lasting hit from the current coronavirus epidemic.

Supply scarcity lifts average costs

Average prices paid for inputs meanwhile rose at a slightly faster rate in February, the overall pace of increase hitting a nine-month high. While weaker global commodity prices helped reduce firms' costs, prices for some inputs rose amid increased scarcity of supply.

Average selling prices fell marginally, down for the first time in four months, as February saw increased numbers of firms discounting prices to boost sales.

China leads downturn with record slump, rest of world stagnates

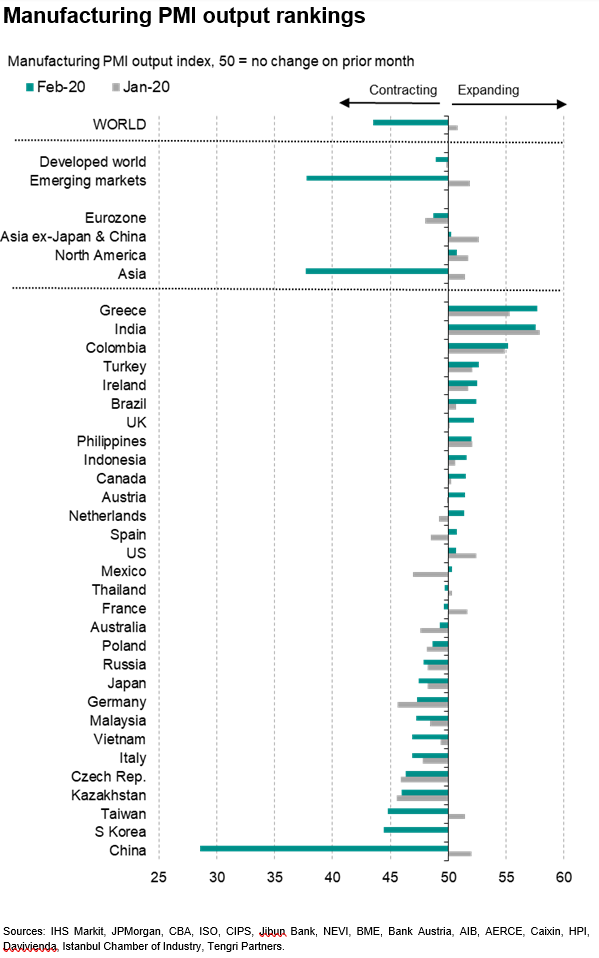

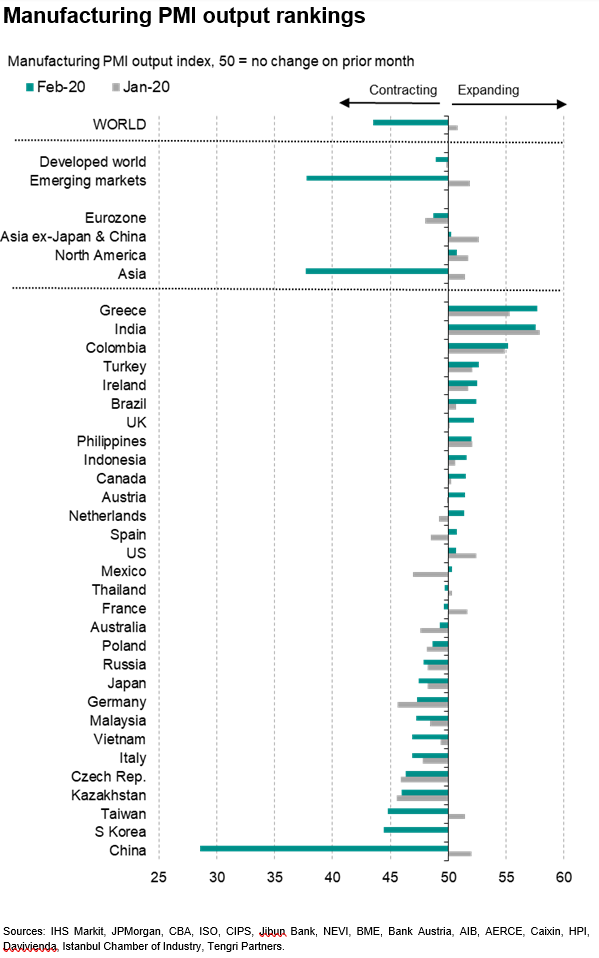

Looking in more detail at country trends, it becomes clearer as to the impact of China on the global manufacturing economy. The Caixin PMI for mainland China slumped from 51.1 to 40.3, its lowest in the near 16-year history of the survey. If we exclude China from the calculations, the global manufacturing PMI merely fell fractionally from 50.1 to 50.0, indicating stagnation rather than decline. Similarly, both output and new orders fell only slightly into decline in February if China is excluded.

Some 15 of the 30 countries so far surveyed in February reported higher production, led by Greece followed by India. Other notable countries reporting higher production included the UK, where businesses have reported an ongoing post-election rebound so far this year, while Canada and Mexico enjoyed the largest output gains for a year, and Brazil saw a welcome upswing in production.

Output across North American continued to grow, albeit only modestly and at the weakest rate for six months, largely on the back of a marked slowing in US factory production growth to a seven-month low.

The other 15 economies reported falling output, with the list, besides China in Asia-Pacific, including South Korea and Taiwan, both of which saw output contract at rates rarely exceeded since 2009, as well as Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand and Australia.

Asia ex-China saw output slide back into decline as a result, having risen modestly in January for the first time in seven months.

Eurozone output meanwhile continued to fall, though the drop in production was the smallest for nine-months. Output fell in Germany, Italy and France, with weakness also evident further east, with downturns seen in Russia, Poland and the Czech Republic.

Supply chains key to future production

Key to whether global production picks up or slumps lower will depend to a material extent on the re-establishment of functioning supply chains out of China. Production facilities are slowly coming back on-line after extended New Year holiday closures, designed to limit the spread of the coronavirus. However, the PMI results reveal that even towards the end of February many firms were reporting that production was yet to restart or was running well below capacity, limited in part by restrictions on travel for workers and input shortages.

The prospect of lengthening of lead-times bodes ill for production in many countries. Even excluding China, global delivery times lengthened in February to the greatest extent since late-2018, when surging global demand put pressure on suppliers.

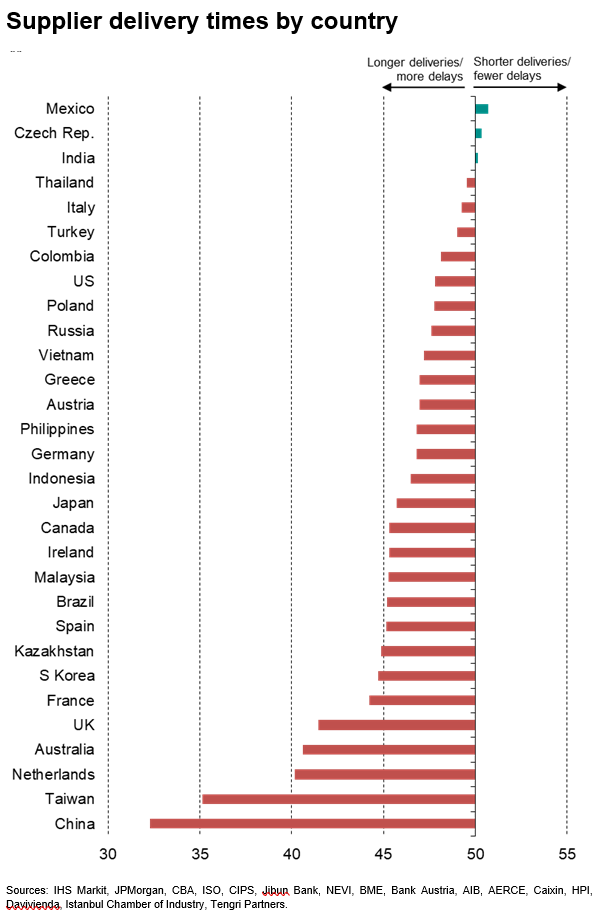

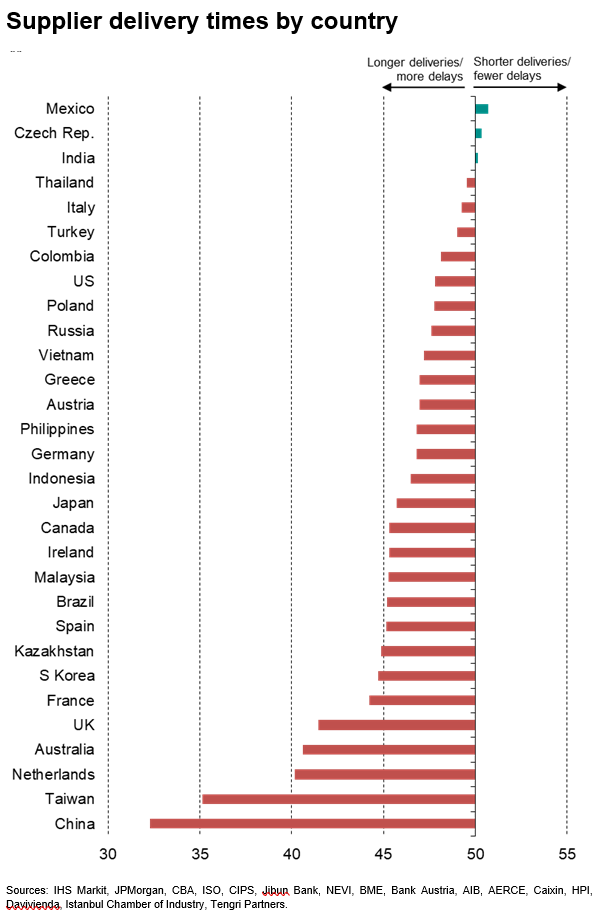

Only three of the 30 countries so far surveyed reported improved supplier delivery times: Mexico, the Czech Republic and India.

Besides China, the greatest incidences of delays were seen in Taiwan, the Netherlands and Australia, followed by the US and France. Importantly, some of the countries currently showing the greatest resilience to the coronavirus outbreak, notably in Europe, are also seeing marked lengthening of lead-times, hinting that production could wane in March unless supply chains are restored.

"Disclaimer: The intellectual property rights to these data provided herein are owned by or licensed to Markit Economics Limited. Any unauthorised use, including but not limited to copying, distributing, transmitting or otherwise of any data appearing is not permitted without Markit’s prior consent. Markit shall not have any liability, duty or obligation for or relating to the content or information (“data”) contained herein, any errors, inaccuracies, omissions or delays in the data, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon.

In no event shall Markit be liable for any special, incidental, or consequential damages, arising out of the use of the data. Purchasing Managers' Index™ and PMI™ are either registered trademarks of Markit Economics Limited or licensed to Markit Economics Limited. Markit is a registered trade mark of Markit Group Limited."

Global manufacturing contracted at the fastest rate in over a decade during February as the coronavirus disrupted supply chains and hit demand, according to PMI survey data. The downturn was led by a record slump in activity at China's factories, with the rest of the world stagnating. The answer as to whether production will revive or turn down in coming months will depend both on supply chains and demand.

Output, new orders and trade show biggest slumps since 2009

The JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM) Global Manufacturing PMI, compiled by IHS Markit from its surveys in 31 markets, fell 3.2 points from 50.4 in January to 47.2 in February, its lowest since May 2009 and signalled a renewed steep deterioration in the health of worldwide manufacturing.

To get a better understanding of the true depth of the downturn we need to look at the PMI's sub-components. The PMI is a weighted average of five survey variables: new orders, output, employment, suppliers' delivery times and inventories of purchased inputs. Both output and new orders fell at even faster rates than the headline PMI, the latter having been buoyed to some degree by longer delivery times. Longer deliveries are normally a sign of a busier economy, and hence boost the PMI. However, at present, longer deliveries are almost entirely due to virus-related shutdowns, according to survey replies.

Looking at the current indices of output and demand, the monthly drop in worldwide factory production was the steepest since April 2009, the output index dropping some 7.3 points compared to January. The new orders index meanwhile slumped 5.6 points to also reach its lowest since April 2009, in part reflecting the largest slide in global exports for over ten years as demand for goods fell sharply.

Factory jobs were meanwhile cut globally at the fastest rate since August 2009 as companies scaled back production capacity in line with falling demand and the reduced supply of inputs.

Near-record delivery delays as coronavirus disrupts supply chains

The extent of supply chain delays was reflected in the second-longest lengthening of suppliers' delivery times since global production growth boomed in 2004. The current lengthening was exceeded only by the delays seen in April 2011 after the Japanese earthquakes. Importantly, like 2011, the latest delivery times lengthening was due to a supply shock (rather than strong demand, as in 2004), linked by many companies to delays in the provision of inputs due to extended virus-related factory shutdowns in China.

Global inventory holdings of inputs fell to the greatest extent since November 2009 largely as a result of the supply limitations. Similarly, stock of finished goods fell to the sharpest degree for almost four years, reflecting constrained production in many companies.

The constraints on production from limited supply availability led to a rise in backlogs of work for the first time since December 2018, with the accumulated volume of uncompleted orders rising to the greatest extent for just over one and a half years. This build-up clearly hints at a rebound in production as these backlogs can be fulfilled when new supplies of inputs can be sourced. Indeed, companies' expectations of their output growth over the coming year remained largely unchanged on the near-one-and-a-half year high seen in January. However, much will depend not just on the speed with which supply chains can return to normal, but also on whether demand takes a deeper and more long-lasting hit from the current coronavirus epidemic.

Supply scarcity lifts average costs

Average prices paid for inputs meanwhile rose at a slightly faster rate in February, the overall pace of increase hitting a nine-month high. While weaker global commodity prices helped reduce firms' costs, prices for some inputs rose amid increased scarcity of supply.

Average selling prices fell marginally, down for the first time in four months, as February saw increased numbers of firms discounting prices to boost sales.

China leads downturn with record slump, rest of world stagnates

Looking in more detail at country trends, it becomes clearer as to the impact of China on the global manufacturing economy. The Caixin PMI for mainland China slumped from 51.1 to 40.3, its lowest in the near 16-year history of the survey. If we exclude China from the calculations, the global manufacturing PMI merely fell fractionally from 50.1 to 50.0, indicating stagnation rather than decline. Similarly, both output and new orders fell only slightly into decline in February if China is excluded.

Some 15 of the 30 countries so far surveyed in February reported higher production, led by Greece followed by India. Other notable countries reporting higher production included the UK, where businesses have reported an ongoing post-election rebound so far this year, while Canada and Mexico enjoyed the largest output gains for a year, and Brazil saw a welcome upswing in production.

Output across North American continued to grow, albeit only modestly and at the weakest rate for six months, largely on the back of a marked slowing in US factory production growth to a seven-month low.

The other 15 economies reported falling output, with the list, besides China in Asia-Pacific, including South Korea and Taiwan, both of which saw output contract at rates rarely exceeded since 2009, as well as Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand and Australia.

Asia ex-China saw output slide back into decline as a result, having risen modestly in January for the first time in seven months.

Eurozone output meanwhile continued to fall, though the drop in production was the smallest for nine-months. Output fell in Germany, Italy and France, with weakness also evident further east, with downturns seen in Russia, Poland and the Czech Republic.

Supply chains key to future production

Key to whether global production picks up or slumps lower will depend to a material extent on the re-establishment of functioning supply chains out of China. Production facilities are slowly coming back on-line after extended New Year holiday closures, designed to limit the spread of the coronavirus. However, the PMI results reveal that even towards the end of February many firms were reporting that production was yet to restart or was running well below capacity, limited in part by restrictions on travel for workers and input shortages.

The prospect of lengthening of lead-times bodes ill for production in many countries. Even excluding China, global delivery times lengthened in February to the greatest extent since late-2018, when surging global demand put pressure on suppliers.

Only three of the 30 countries so far surveyed reported improved supplier delivery times: Mexico, the Czech Republic and India.

Besides China, the greatest incidences of delays were seen in Taiwan, the Netherlands and Australia, followed by the US and France. Importantly, some of the countries currently showing the greatest resilience to the coronavirus outbreak, notably in Europe, are also seeing marked lengthening of lead-times, hinting that production could wane in March unless supply chains are restored.

"Disclaimer: The intellectual property rights to these data provided herein are owned by or licensed to Markit Economics Limited. Any unauthorised use, including but not limited to copying, distributing, transmitting or otherwise of any data appearing is not permitted without Markit’s prior consent. Markit shall not have any liability, duty or obligation for or relating to the content or information (“data”) contained herein, any errors, inaccuracies, omissions or delays in the data, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon.

In no event shall Markit be liable for any special, incidental, or consequential damages, arising out of the use of the data. Purchasing Managers' Index™ and PMI™ are either registered trademarks of Markit Economics Limited or licensed to Markit Economics Limited. Markit is a registered trade mark of Markit Group Limited."