(Bloomberg) -- The U.S.’s biggest oil field may be about to pump the brakes if crude keeps plunging.

Just 10 weeks ago, the Permian Basin was on course to grow almost 1 million barrels a day by the end of 2019, potentially surpassing Iraq, OPEC’s second-largest producer. Now, it may not grow at all, removing a large chunk of expected production from global oil markets.

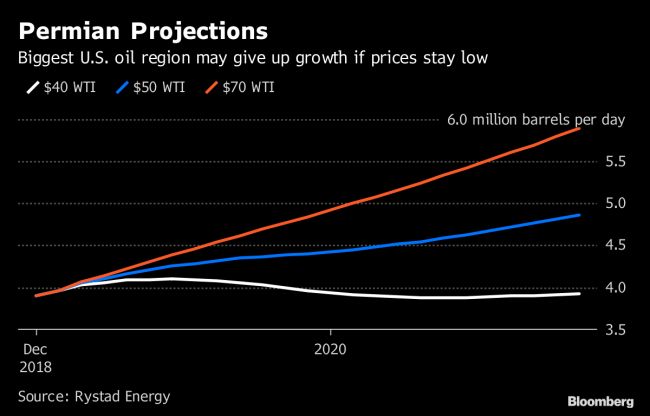

Shale is highly sensitive even to small changes in prices and the Permian is not immune. With West Texas Intermediate oil at $70 a barrel, the basin would likely produce 4.9 million barrels a day by end of next year, but at $40, output will likely stagnate at around 4 million barrels a day, according to Oslo-based consultancy Rystad Energy.

The U.S. benchmark dipped below $46 in New York on Tuesday, down almost 40 percent from early October. In Midland, the heart of the Permian, prices were even worse, touching $38.99 a barrel, the lowest since the depths of the 2016 crash.

“We’ll definitely see some companies next year revisit their activity plans versus what they initially had in mind,” said Artem Abramov, vice president of shale analysis at Rystad.

It’s already starting to happen. Diamondback Energy Inc., one of the biggest Permian-only producers, is rowing back its 2019 capital budget, forecasting about $2.9 billion of spending, less than analysts’ estimates of $3.2 billion. Chief Executive Officer Travis Stice said the “dramatic decline in oil prices” were to blame as well as higher service costs.

Breakevens for new wells in various counties that contain the Spraberry layer of oil-soaked rock in the Permian currently average between $32 to $47 a barrel, according to Bloomberg NEF data. But well performance varies substantially. In Upton County, for example, top-quartile wells make money at $31 a barrel, while the bottom quartile need $65.54 a barrel.

“BNEF’s break-even model calculates that an average Permian well can produce oil for under $50 a barrel, but only the top performers in the Denver-Julesburg or Bakken can match that,” BNEF analyst Tai Liu said Friday in a research note.

The Permian’s better productivity means output isn’t dropping, just slowing down, if oil averages $50 a barrel and halting growth at $40, Rystad said. IHS Markit and RS Energy, agree that modest growth is likely at current prices because companies in the Permian have dropped their well costs so much over the last four years through productivity improvements.

“There’s a lot less cash flow to go around but it’s not an existential threat like it was in 2014,” said Ian Nicholson at RS Energy, referring to the oil-price crash of that year. Higher-cost production in the Bakken in North Dakota and Eagle Ford in south Texas are more susceptible to the recent price plunge, he said.

One of the key advantages of shale is that crude flows from wells within weeks of drilling, rather than years for large, offshore megaprojects that defined the production growth in the early 2000s. That means shale can be turned on or off like a tap, depending on whether it’s profitable or unprofitable at any given price. That may be of no consolation to equity investors starved of earnings, cash flow and dividends but it does help to rebalance oil markets.

“If we don’t get those barrels in 2019, they will simply be waiting to show up in 2020, or 2021, or whenever the market needs them,” said Raoul LeBlanc, a Houston-based analyst at IHS Markit. “The eventual limit is sweet spot exhaustion, and in the Permian, that will not happen in the next seven years.”