Proactive Investors - Monday saw the government renew commitments to North Sea oil and gas, paired with an update on the UK’s ambition to roll out carbon capture en masse.

Though dwarfed by the controversial confirmation that hundreds upon hundreds of new oil and gas licences would be granted in UK waters, Monday’s announcement also confirmed areas in the Humber and Scotland would be used as carbon capture “clusters”.

Dubbed projects ‘Acorn’ and ‘Viking,’ the plans will see carbon capture installed in the industrial areas by 2030, following the conversion of two other sites this decade.

These projects will ultimately aim to reduce emissions from the UK’s industrial sector, Aided by a promised £20bn in government funding.

However, given the ambitious nature of the government’s master plan to pump this captured carbon under the North Sea rather than release it, questions have been raised.

So how does it work?

Carbon capture has long since been suggested as a tool for aiding to UK’s journey toward net zero, with the idea in essence centred around preventing emissions from reaching the atmosphere.

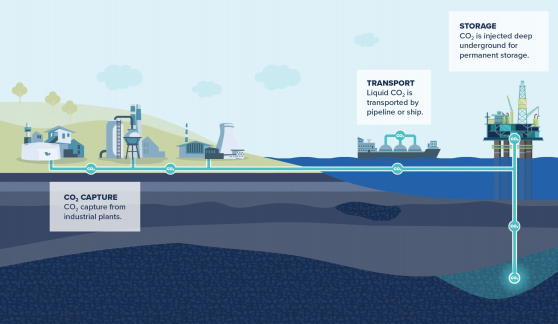

This is done by separating carbon dioxide emitted from the likes of factories, compressing it to be transported via pipes or ship to former storage sites, such as depleted, oil reserves, where it is then injected for permanent storage.

Given empty wells off UK shores promise enough storage for the equivalent of the country’s emissions since the industrial revolution, it is hardly a surprise such plans have been laid out.

According to the North Sea Transition Authority, this figure equates to around 78 gigatons of storage capacity, with prospective investment in the sector worth £220bn by 2030.

Energy and industry, in particular, present likely candidates for the technology, the National Grid (LON:NG) explains, given technology can be built into existing static infrastructure.

Drax Group (LON:DRX), for instance, has plans in place to retrofit its north Yorkshire-based biomass energy plant with carbon capture technology in order to restrict emissions.

Though the FTSE 250-listed generator is yet to confirm the multi-billion-pound investment given its previous qualms over government support, Drax did hail Monday’s news.

“The announcement shows the importance of [and] creates an additional pathway to support our plans for bioenergy with carbon capture and storage at Drax Power Station.

“We are currently engaged in productive discussions with the UK Government on this project,” the company commented, with its power site situated near the ‘Viking’ site.

Viking and Acorn projects

By using existing infrastructure, the Acorn and Viking carbon capture projects will aim to provide industrial emitters in Scotland and near the Humber estuary with ways to transport their captured emissions.

According to London-listed Harbour Energy (LON:HBR), which is involved in both projects, the latter alone could see 15mln tonnes of CO2 captured and stored annually by 2035.

Some £7bn of investment could be unlocked by the plan, Harbour added, providing a boost for the Humber region while aiding the UK’s targeted 30mln tonnes of stored carbon by 2030.

Shell PLC (LON:SHEL), the technical lead of the Acorn project, dubbed the plans as “central” in decarbonising both North Sea and industrial operations meanwhile.

Criticism

However, not everyone is so convinced by the use of carbon capture.

Aside from the rosy comments from those involved, climate activists and experts have raised doubts over the idea echoing the same main point: carbon-emitting fuels are still being burned.

Climate group Greenpeace accused oil and gas companies of using carbon capture as a means of “greenwashing,” arguing it simply allows the sector to continue polluting.

“It’s worth noting that carbon capture is not zero carbon [and] is unlikely to see dramatic cost reductions or be scalable,” the group said.

Leaks from storage sites could potentially wipe out efforts to prevent carbon from reaching the atmosphere meanwhile, the London School of Economics has argued previously, also raising concern over the high costs of such projects.

Read more on Proactive Investors UK