Prior to the last several years, modeling the gold market was relatively straightforward. But a lot has changed in recent history, and so has the mix of factors that are front and center in gold’s price trend.

In past decades a simple two-factor model was relatively robust for estimating gold’s “fair value.” The first factor: the US dollar. Widely seen as an alternative to fiat currencies (the greenback, in particular), a fair degree of negative correlation persisted between the dollar and the precious metal.

The second factor: real interest rates. When inflation-adjusted yields are low or negative, the relative appeal of gold, which is forever a 0% yielding asset, is stronger because the opportunity cost of holding it is lower. The opposite is also true: high real yields are a competitive threat to holding 0%-yielding gold.

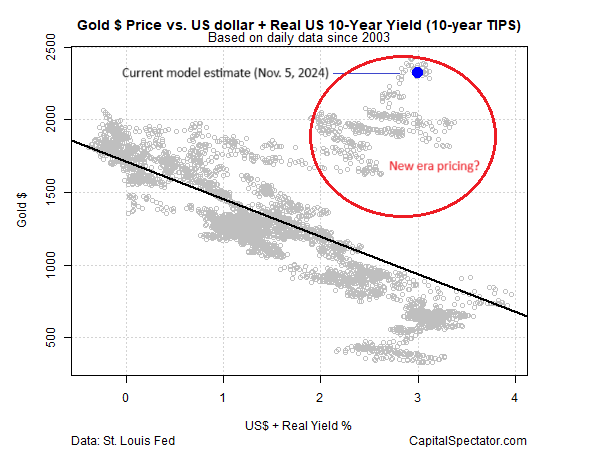

For several decades this relationship was relatively robust. But recent history has upended this relationship — a change that blinded CapitalSpectator.com in recent “fair value” modeling observations, such as here.

Consider, for instance, that the sharp rise in real yields (based on inflation-indexed Treasuries) post-pandemic has had little, if any, effect on gold’s price, which has surged to record highs lately. The US Dollar Index also surged after the pandemic, although it’s recently eased to trade in a middling range vs. recent history.

Despite these factors, gold has risen from around $1,500 an ounce at the end of 2020 to $2,746 (as of Nov. 4, 2024). The gold model that worked relatively well, in short, has broken down, as the chart below suggests.

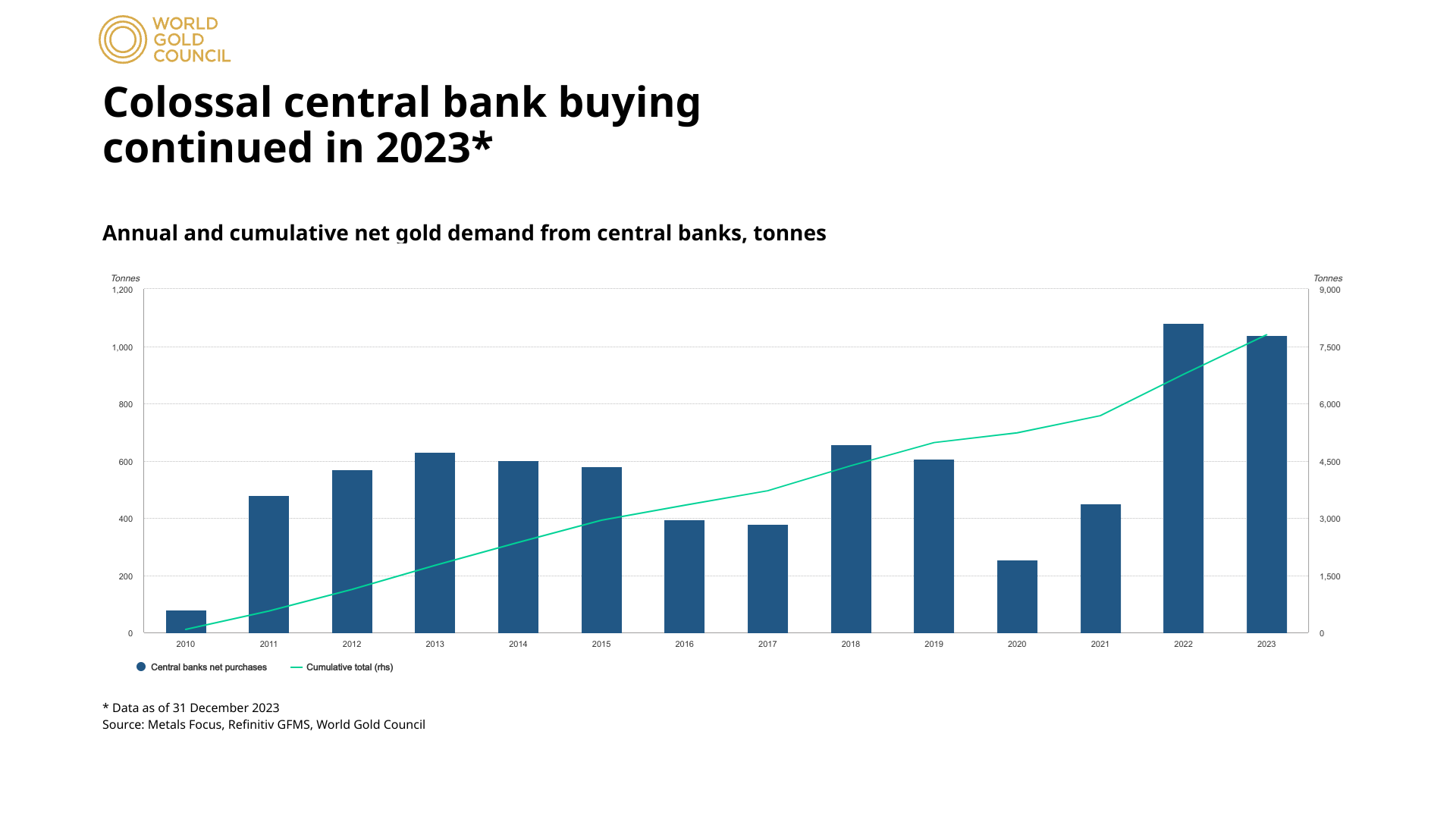

What’s driving gold these days? No one can say for sure, but two factors deserve to be on the short list of likely candidates: central bank purchases of the metal and hedging strategies designed to offset blowback in a dangerous world. Both factors are, of course, familiar inputs for modeling gold through history. But both have been in remission, so to speak, until the several years.

Central banks have ramped up purchases of gold, reports the World Gold Council, a trade group. For example, these banks bought more than 1,000 of gold in 2022 and 2023 – an unprecedented level of buying.

News headlines in the past couple of years have also fed worries that geopolitical and geoeconomic risk has increased, which in turn has fed demand for the perceived safe haven of gold. Advocates of the precious metal have an easy time of listing worrisome events, ranging from wars in the Middle East and Ukraine to tensions between the US and China and a deteriorating fiscal outlook for America’s federal government, the latter receiving virtually no attention from the presidential candidates.

The implication of all this is that modeling gold requires a revision that emphasizes central bank buying (or selling) activity and one or more proxies for perceptions on global risk. Real yield and the US dollar are still relevant, but not at the moment, or so it appears.

The bigger lesson is that risk factors that “explain” market pricing are in constant flux. If nothing else, recent events in the gold market highlight the fact that so-called physics envy on Wall Street, and in the investment world generally, is well founded and always will be.