Profitable bond trading opportunities arise when your expectations about Fed policy differ from those of the market. Therefore, with the Fed seemingly embarking on a series of interest rate cuts, it behooves us to appreciate how many interest rate cuts the Fed Funds futures market expects and over what period.

Equally important, Fed Funds futures help us assess the market’s economic growth and inflation expectations. Currently, Fed Funds futures imply the Fed will start cutting rates in September and reduce them by 2.25% to 3.09% in early 2026.

From that point, the market expects the Fed to slowly increase Fed Funds to 3.50%. The limited rate cuts and relatively high trough in Fed Funds tell us the market is not pricing in a recession but normalization of GDP with inflation running at or slightly above the Fed’s 2% target.

If the Fed Funds futures market is correct, the upside in bond prices may be limited, especially compared to prior easing cycles.

However, suppose the market underestimates the probability of a recession or a sharper-than-expected inflation drop over the coming few years. In that case, there is significant upside potential in bond prices.

Fed Funds Futures Caveat

Before we provide historical context for what the Fed might do and a historical track record of Fed Funds futures estimates, it’s important to caveat that market beliefs about future Fed actions and, consequently, the economy and inflation can swing wildly.

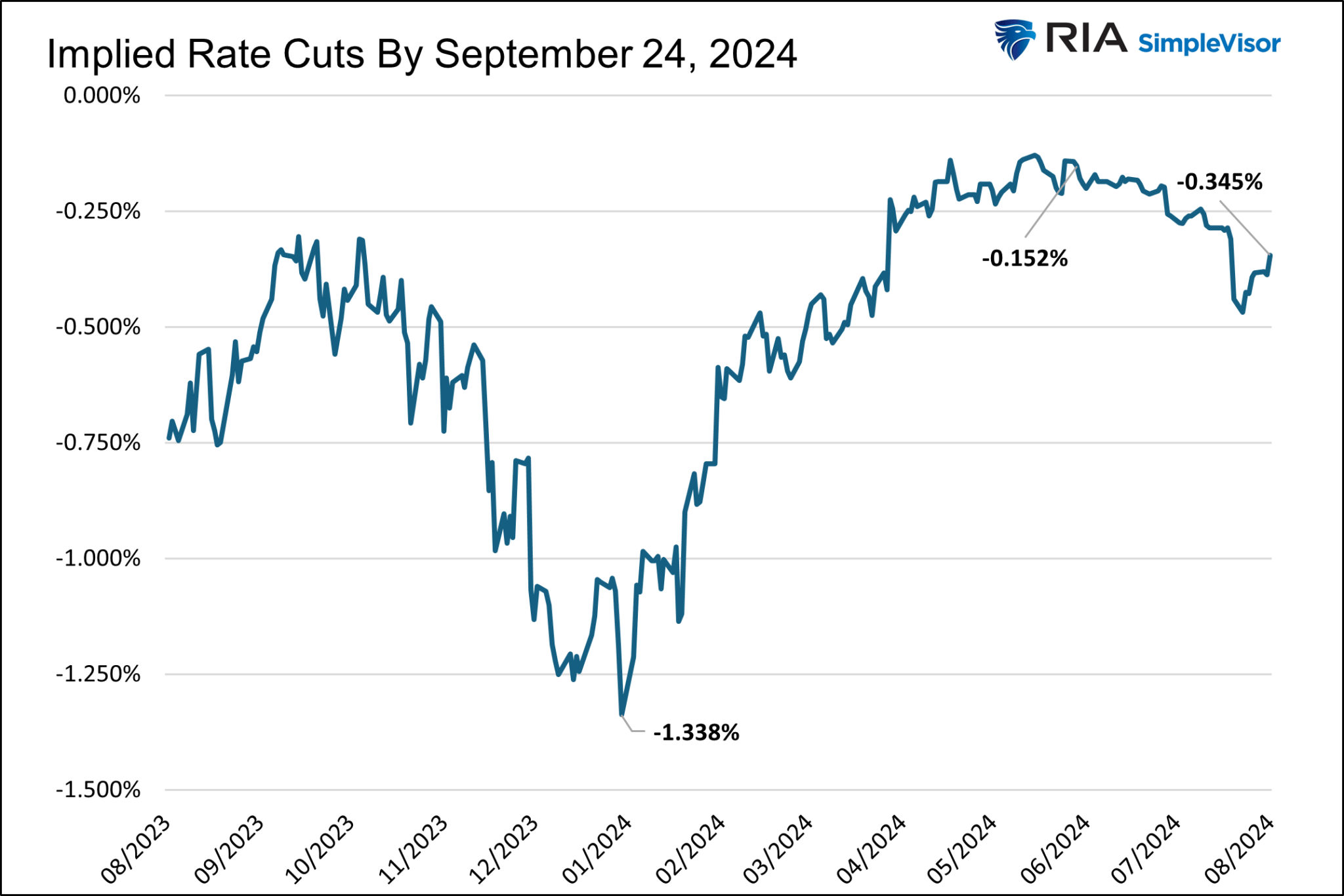

The graph below shows that expectations for the Fed Funds rate at the coming September 24th FOMC meeting have whipped around over the past year. Fed Funds futures currently imply that the Fed will cut rates by 34 bps at the September meeting.

This includes a 100% chance of 25 bps and a 36% (.34-.25)/.25) chance of 50 bps. Only two months ago, it was priced at a 50/50 chance of only one 25-bps rate cut.

Furthermore, at the start of the year, the market thought the Fed would cut rates by 1.34% by next month’s meeting. The data suggest that the markets’ collective assessment of economic conditions can be volatile.

Fed Funds and Fed Funds Futures

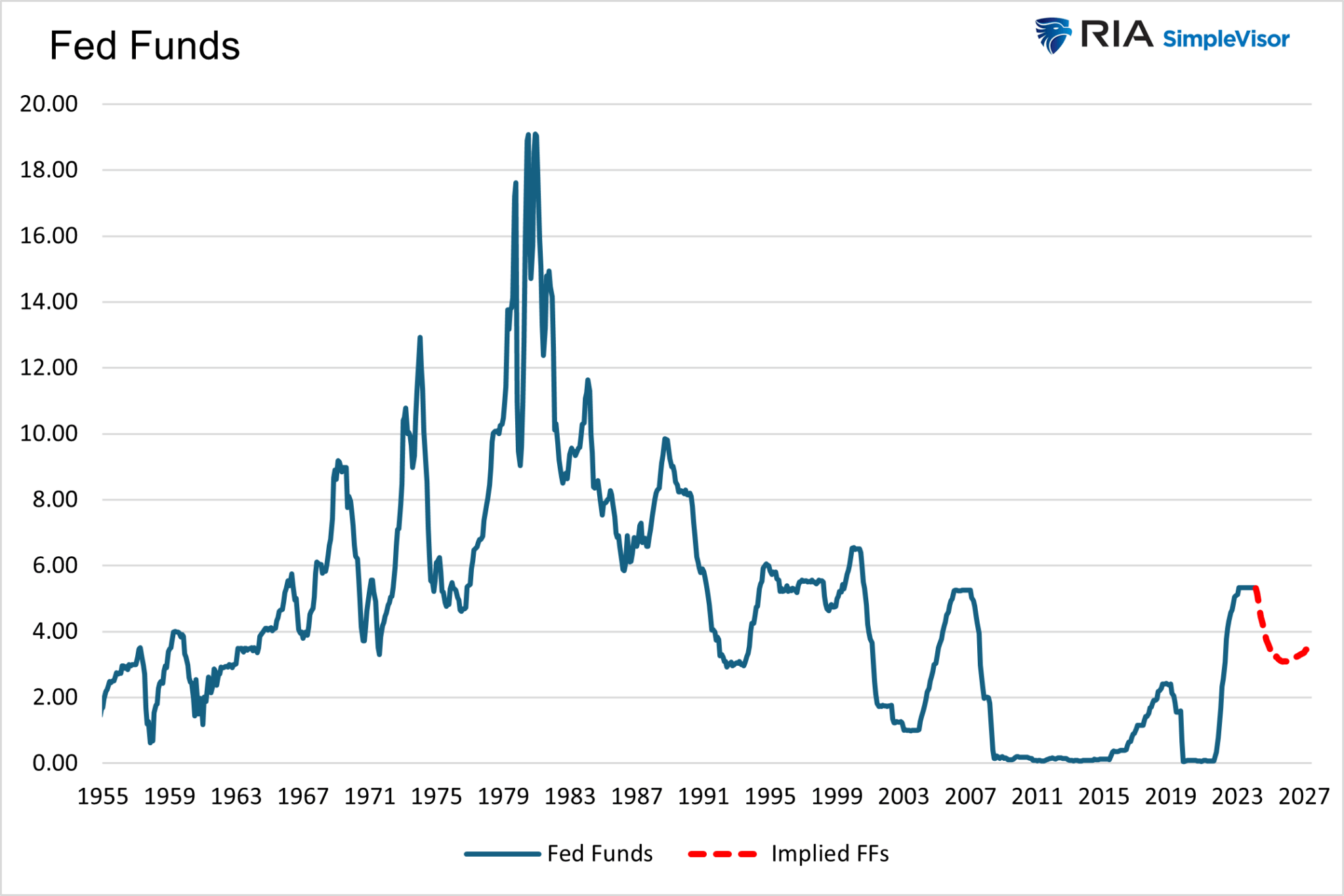

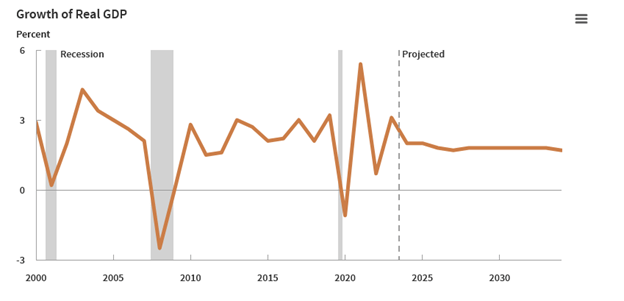

The graph below charts the effective Fed Funds rate since 1955. As implied by Fed Funds futures, we added the future rates for the next three years.

The market expects Fed Funds to decline from the current rate of 5.33% to 3.09% by March 2026. Following that, Fed Funds futures imply Fed Funds will slowly rise to 3.50% by the end of 2027.

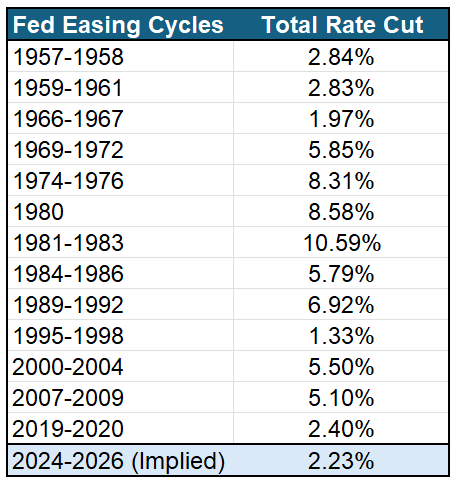

The table below quantifies the thirteen easing cycles shown above. Of these easing cycles, only two periods saw declines of less than 2.23%. 2.23% represents current market expectations. Of the two instances, the economy did not enter a recession (1966-1967 and 1995-1998).

Since 1980, only two easing cycles have seen the Fed cut Fed Funds by less than 5%. The most recent, 2020, was limited as the Fed could only bring rates down to 0%. The other was 1995-1998.

Based on history, the market is betting on an anomaly, like 1995-1998, and not normal monetary policy behavior.

What Is The Market Expecting?

Given that the market expects a relatively minimal rate cut, we should suppose it’s expecting a 1995-1998 economic scenario, i.e., no recession.

John Authers of Bloomberg recently opined what Fed Funds futures may imply regarding inflation. To wit:

So even if markets buy the notion that the Fed will have to cut soon, they also seem convinced by the theory that the very low rates of the last three decades were an aberration, and that the norm for monetary policy will be tighter in future. That presumably goes hand-in-hand with slightly higher inflation rates.

Presuming the collective market thinks this time is different, they must believe that economic growth and inflation trends of the pre-pandemic have been reversed. We have discussed such a forecast many times. To wit, we share a section from Our Elevator Pitch For Bonds, published in July 2023.

Our view of the attractiveness of bonds can be honed into an elevator pitch. It essentially boils down to a straightforward question – Is this time different? Have the forty-year pre-pandemic economic trends reversed, and the economy’s inner workings changed permanently over the last three years? More specifically, are slowing productivity growth, weakening demographics, and rising debt levels about to reverse their prior trends and become a tailwind for economic growth?

If you think, as we do, that the last three years are an economic, fiscal, and monetary anomaly, then the opportunity to earn 4% or more on a longer-term bond is a gift.

We think yields will revert to low levels when the pre-pandemic economic and inflation trends reemerge. Negative interest rates are not out of the question.

Traders Consistently Underestimate The Fed

While the market appears to be pricing a “this time is different” scenario, it frequently prices in such a scenario, only to find out this time is no different.

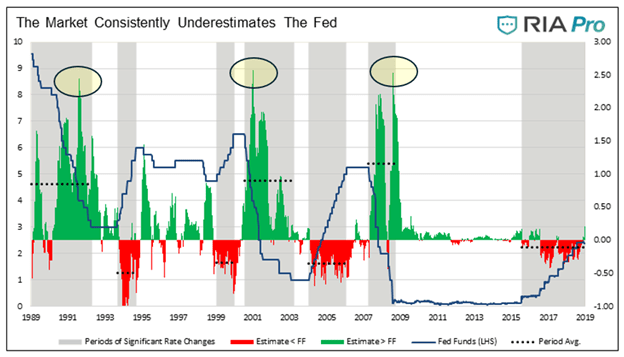

In 2019, we quantified how accurately Fed Funds futures predict the future. The graph below shows our results.

The graph compares the effective Fed Funds rate to what was implied by the futures contract for that same period six months earlier.

The gray shading represents periods in which the Fed consistently raised or lowered the Fed Funds rate. The three easing cycles shown are 1989-1991, 2000-2003, and 2007-2009.

At one point during each of those cycles, the market underestimated the amount of Fed rate cuts by roughly 2.50%. The yellow-shaded circles highlight these gross underestimations.

While not pertinent to this article, the futures market also underestimates rate increases but to a much lesser extent.

In late 2019, when we published the findings, we theorized:

“If the Fed initiates rate cuts and if the data in the graphs prove prescient, current estimates for a Fed Funds rate of 1.50% to 1.75% in the spring of 2020 may be well above what we ultimately see.”

It turns out we were prescient. Fed Funds went to 0%.

What Do Economists Think?

With an idea of what the market forecasts for longer-term economic growth and inflation, let’s compare that to economists’ expectations.

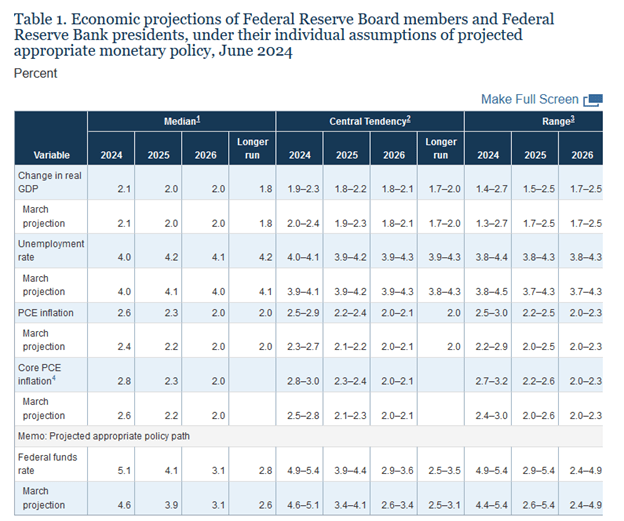

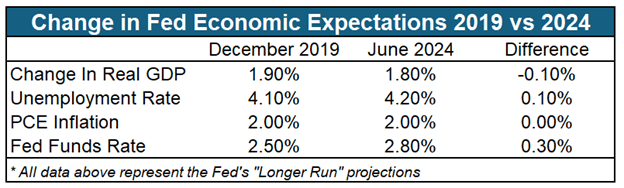

The table below is from the Fed’s most recent series of economic projections. As circled, they forecast the long-term economic growth rate of the U.S. is 1.80%. The second table compares the projections below with those from December 2019.

The difference column shows that the Fed doesn’t believe this time is different. On the contrary, it thinks real GDP in the “longer run” will run 0.1% less than before the pandemic.

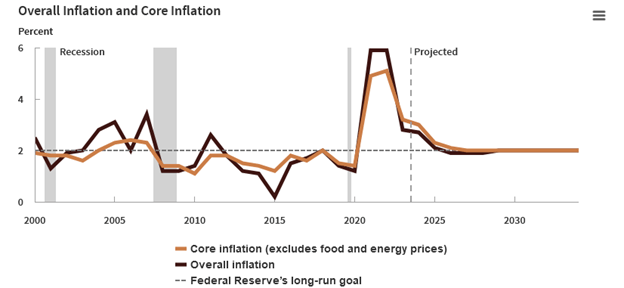

Furthermore, it expects a slightly higher long-term unemployment rate. The Fed believes inflation will run around 2% in the future, as it did in 2019.

The CBO also forecasts that pre-pandemic GDP and inflation trends will prevail over the next decade.

Don’t believe the government?

The following commentary is from the Blue Chip Economic Indicators, compiled by Wolters Kluwer. The report polls 50 leading business economists to arrive at its forecasts.

In general, the longer-term outlook in the most recent survey is little changed from that in the March survey. Forecasters usually anticipate that the real GDP will grow on average at its potential rate over the longer term. The BCEI consensus looks for 1.9% growth in real GDP over the 2025- 29 period, the same estimate as in March but much slower than the 2.5% growth experienced during the five years prior to the Covid pandemic.

On inflation, the consensus expects the Federal Reserve to essentially achieve its 2% target with the PCE price index inflation rate (the measure that the Fed targets) expected to average 2.1% from 2025-29. This is slightly higher than the 2.0% estimate in the March survey.

Both public and private sector economists are forecasting that this time is not different. They believe the pre-pandemic trends of lower economic growth and stable 2% inflation will prevail.

Summary

History shows that Fed Funds futures are volatile and consistently underestimate the amount of Fed easing in a cycle. Their forecast of relatively minimal Fed Fund rate cuts implies that the economy will remain strong and, to some degree, start reversing the economic and price trends existing before the pandemic.

Economists, however, believe that the major factors that drove a steady trend of declining economic growth before the pandemic will continue.

We side with the economists. There is little evidence that productivity and demographic trends have changed. The nation is more indebted today than it was before the pandemic.

Given those essential economic factors remain intact, it’s difficult for us to believe that this time is different. Therefore, should we expect this coming rate-cutting cycle to differ from the past?

If the answer is no, bond investors could be on the cusp of outsized returns.