On Tuesday, China announced a raft of policies aimed at boosting the economy and encouraging consumption. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cut its seven-day reverse repo rate from 1.7% to 1.5%.

The central bank will also cut the amount of funds that lenders must hold in reserve by 0.5ppt, with more cuts expected later this year. And regulators will recapitalize China’s largest commercial banks; their margins and profits had been eroded by fee reductions and interest-rate concessions. On Wednesday, the central bank trimmed the cost of medium-term loans it provides to banks.

Regulators directly targeted the real estate market by lowering the down payment required on second homes from 25% to 15%. It will also offer better terms on loans to state-owned enterprises that are buying unsold apartment inventory from property developers. (The program launched in May has seen slow adoption, with local governments borrowing only Rmb24.7 billion out of the Rmb500 billion local banks made available.)

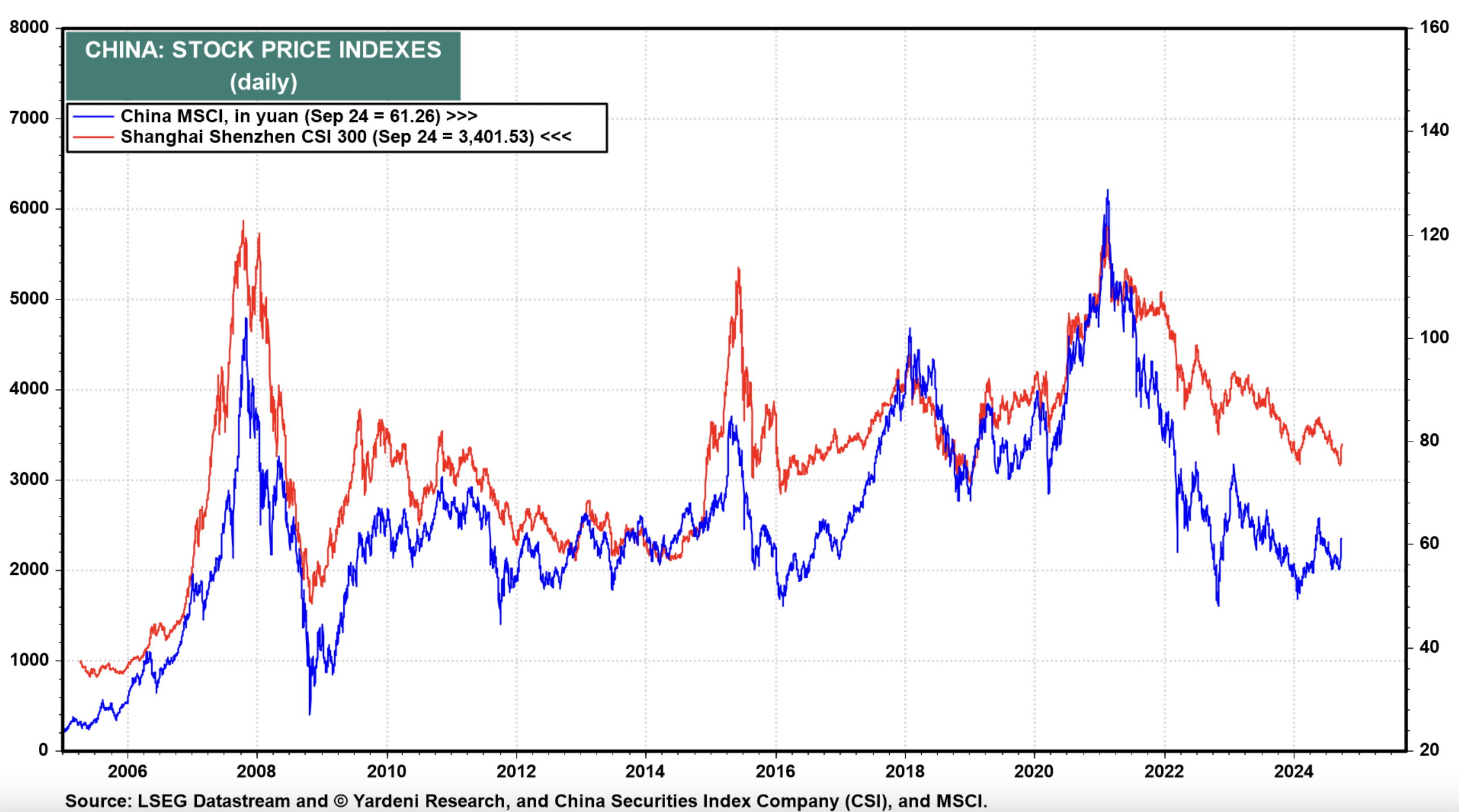

The Chinese stock market received some love as well. Regulators will provide the equivalent of $71 billion to help brokers, insurance companies, and funds buy stocks. The PBoC will also provide $114 billion to help companies buy back shares. Stock investors applauded, sending the Shanghai Shenzhen CSI 300 higher.

The good that these policies do may be offset by Chinese government actions that chill the willingness of consumers and companies to spend and invest in the country.

China’s recent threat to put Tommy Hilfiger’s parent on the national security blacklist doesn’t scream “come and invest in our country.” Neither does the detainment of an economist who criticized leaders in a private online chat. And China’s plan to increase its retirement age certainly won’t improve consumer confidence or encourage people to start spending. It’s almost as if China were writing a guidebook for economies on how to be one’s own worst enemy.

Here's a deeper look at government policies that may hurt future business investment and consumer spending in China more than the PBoC’s latest initiatives will help:

1. How to scare corporations

China’s commerce ministry has threatened to put PVH (NYSE:PVH), the parent company of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, on its national security blacklist for not purchasing cotton from its western Xinjiang region. The company has 30 days to defend itself against the accusation that it has been discriminating against Xinjiang-related products over the past three years.

What was PVH thinking? Merely that it wants to sell its China-made goods in US markets: The US bans goods made in Xinjiang unless importers can prove that they were not made using the forced labor of the Muslim Uyghur population. So China’s blacklist threat places PVH between a rock and a hard place.

Five other companies are on China’s national security blacklist, including Lockheed Martin (NYSE:LMT) and Raytheon (NYSE:RTN) Technologies (NYSE:RTX) due to their sale of weapons to Taiwan. But they have no business in China at risk. PVH, on the other hand, has stores and warehouses in China.

[If placed on the list, the company could] “face fines, have its activities in China restricted, or face other unspecified penalties,” a September 24 FT article reported.

2 How to scare CEOs

Chinese officials placed a prominent Chinese economist under investigation and detention after his posts in a private chat group on WeChat criticized Xi Jinping’s management of the economy. Zhu Hengpeng, who was the deputy director of the Institute of Economics at the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, was detained this spring, a September 24 WSJ article reported.

He joins a growing list of executives—both Chinese and foreign—that the country has detained. A senior executive from Taiwan’s Formosa Plastics Group has been banned from leaving Mainland China since arriving in Shanghai earlier this month, a South China Morning Post article reported on September 19.

The head of China Evergrande’s electric vehicle unit was detained earlier this year. In 2023, more than a dozen senior executives went missing, faced detention, or were subject to corruption probes, a November 10 CNN article reported.

When Jack Ma, perhaps China’s most high-profile tech entrepreneur, disappeared from public view and underwent “supervisory interviews” in 2020 after criticizing the country’s regulators and state-owned banks in a speech, it became instantly clear that no one was immune.

This high-risk environment combined with the sluggish economy have sharply cut venture capital (VC) fundraising and new startups being founded. In 2017, Rmb124.9 billion of VC funds were raised; last year only Rmb16.6 billion was, according to a September 12 FT article.

Likewise, the number of new companies started peaked in 2018 at 51,302; it was down to 1,202 last year. The numbers are on track to fall further this year.

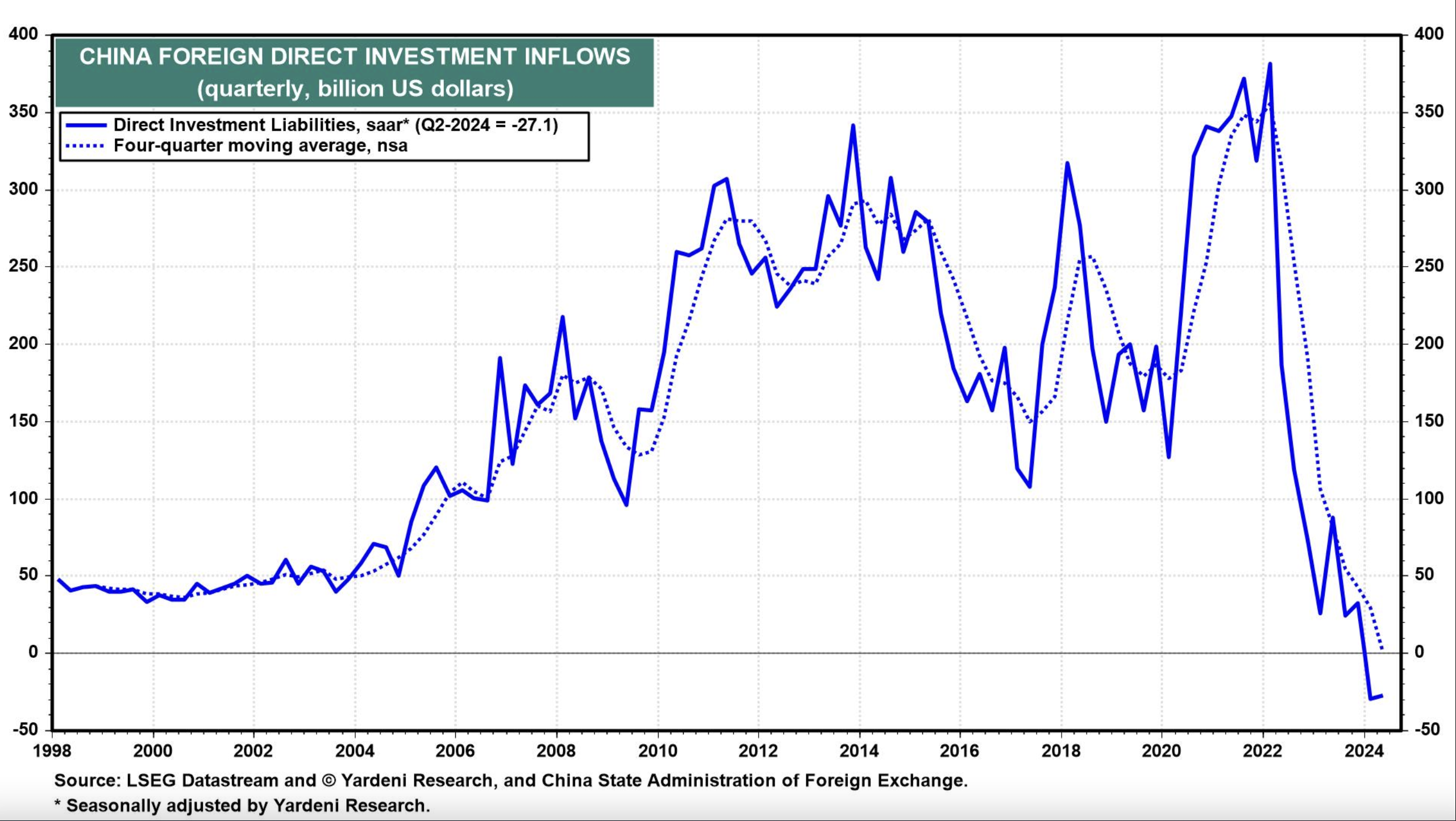

Foreign direct investment (FDI) into China has dropped sharply over the past year too. It peaked at $87.8 billion in Q2-2023 on a quarterly basis; it has subsequently fallen sharply and turned negative in the past two quarters. FDI fell to -$27.1 billion in Q2-2024.

3. How to depress consumers

No one likes to be told that retirement is going to be later than expected, but that’s what happened in China. Starting in January 2025, the retirement age for men in all jobs will jump from 60 to 63. For women in blue-collar jobs, the retirement age will rise from 50 to 55. For women in white-collar jobs, the retirement age will jump from 55 to 58.

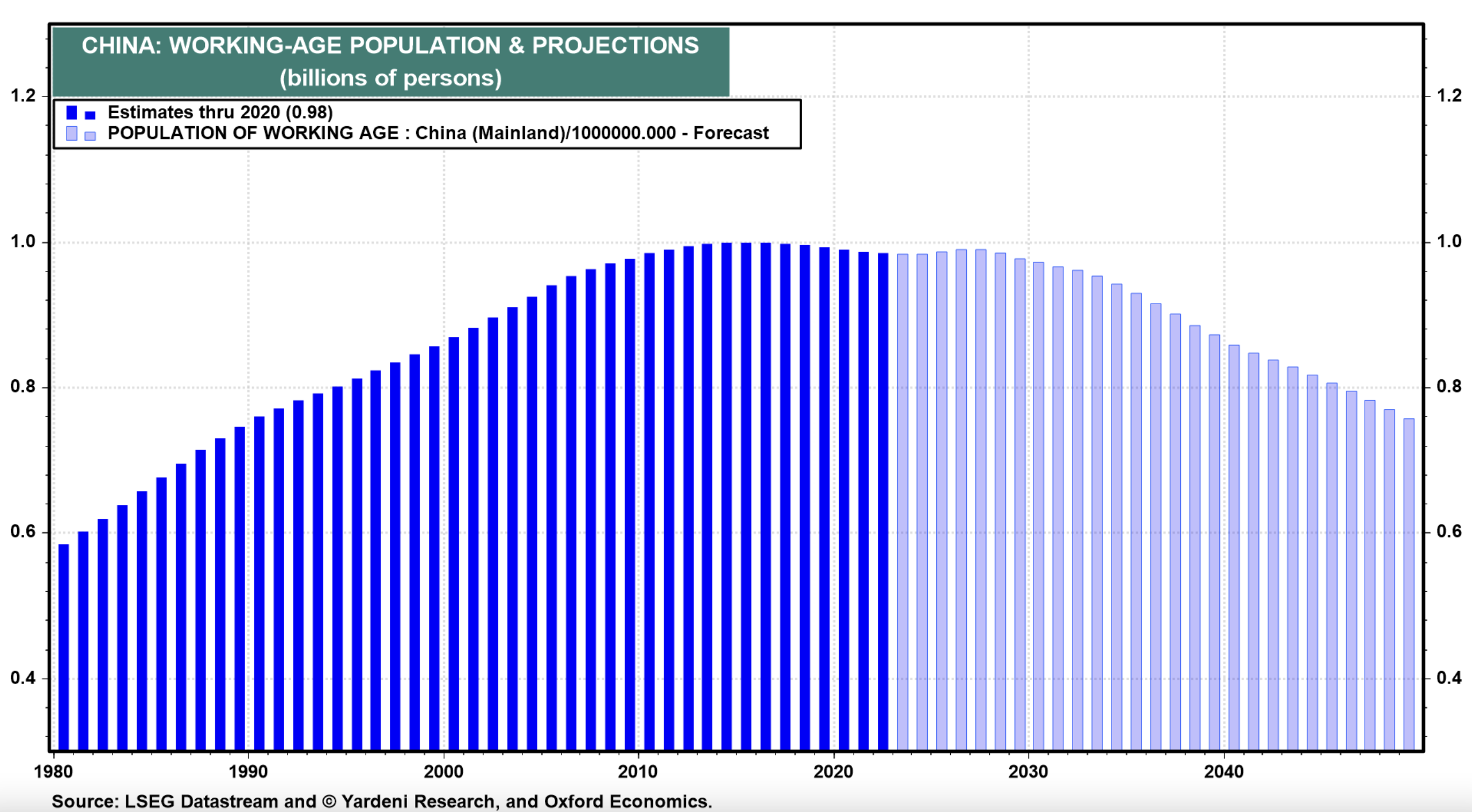

The policy was changed because life expectancies have increased since the policy was established in the 1950s. The move will also increase the working population that pays into China’s pension system. The pension system has come under pressure as China’s birth rate has decreased and its population has aged, leaving fewer young working people to pay into the system to fund disbursements to retirees.

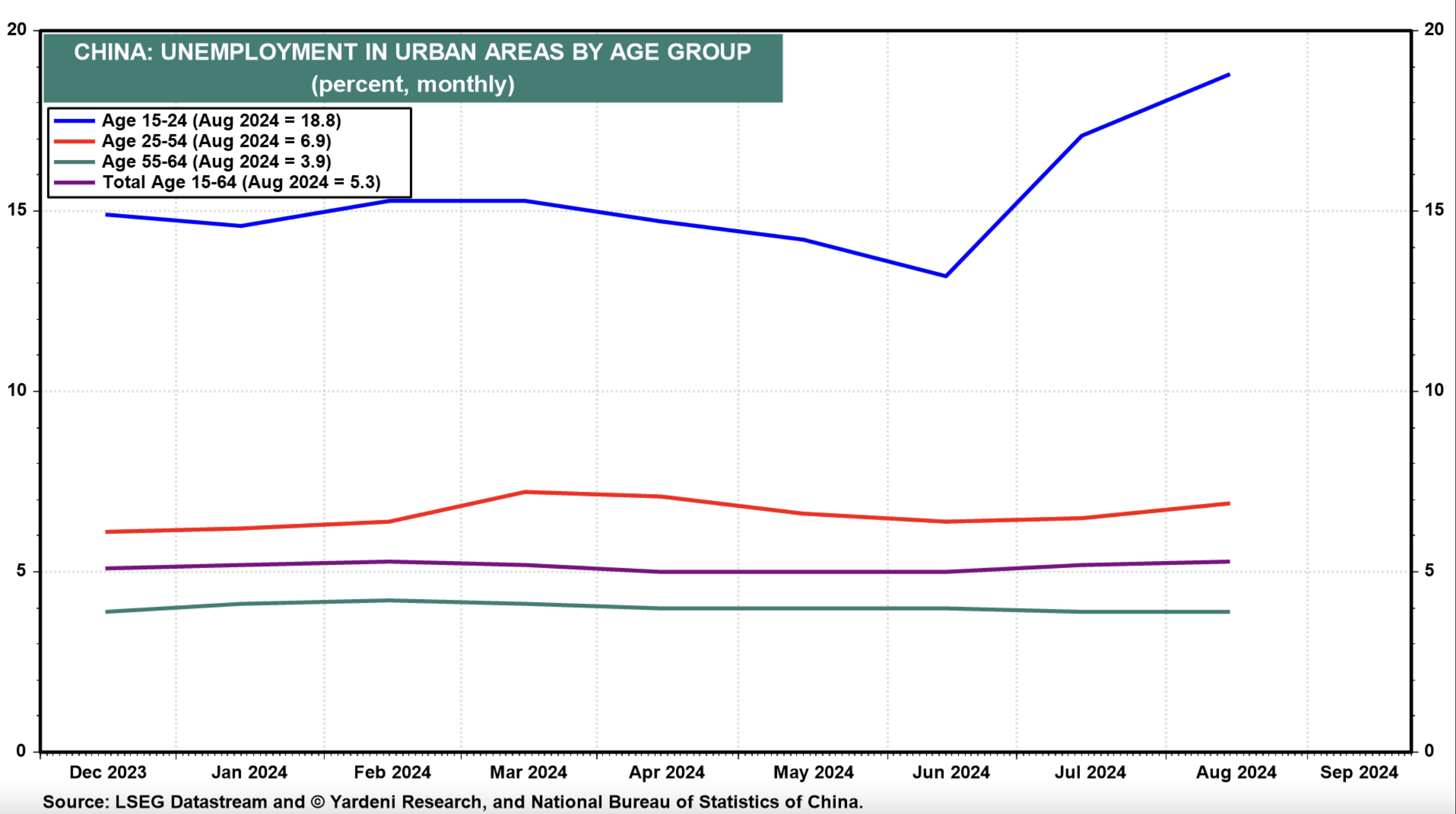

The policy change will extend the life of the pension fund, which was estimated to run out of funds in 2035 if no action was taken. However, it could also exacerbate the high unemployment rate among young workers.

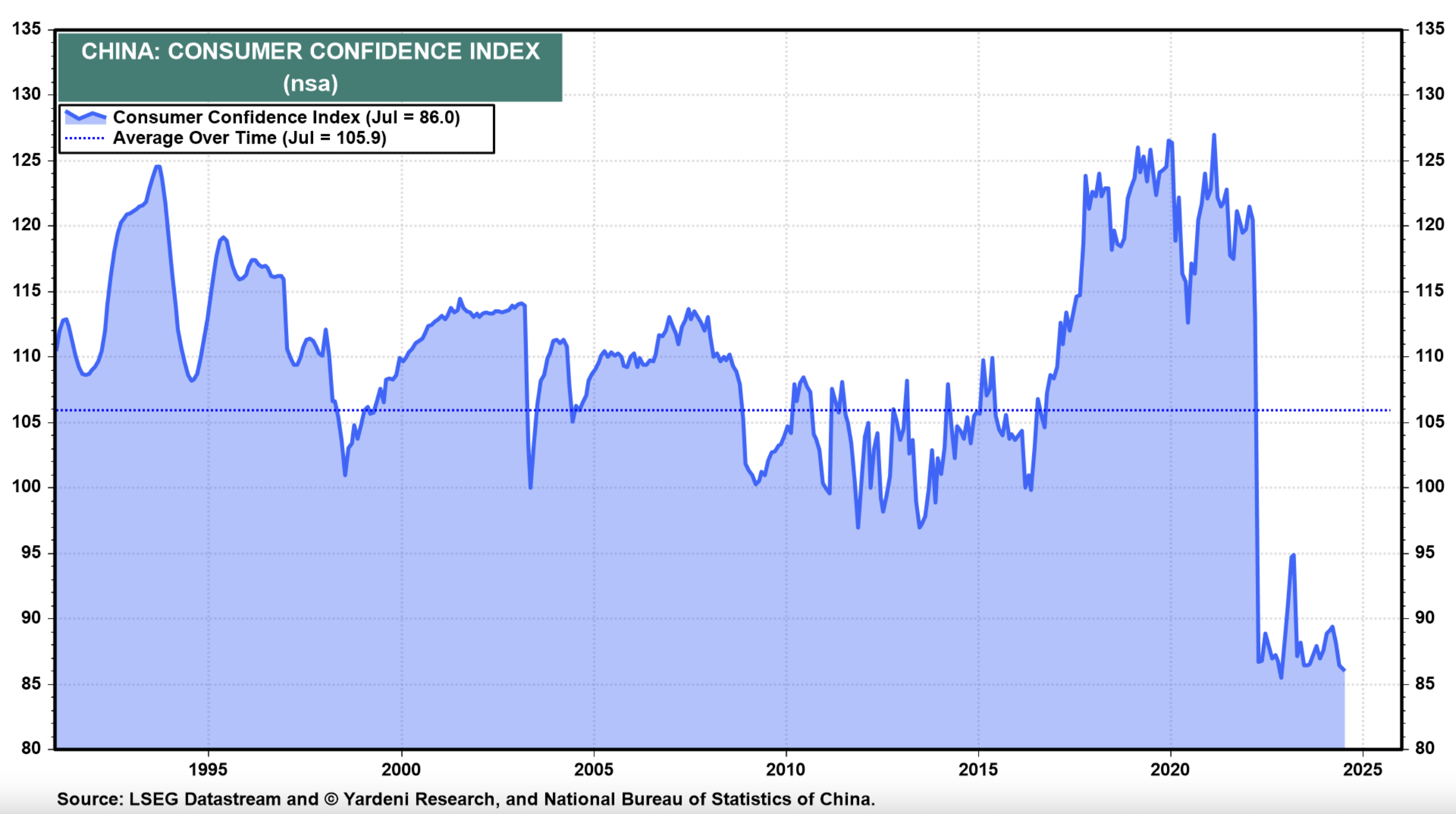

And it’s unlikely to put either the old or young in a spending mood. China’s consumer confidence was already depressed before the change was announced, at 86.0 versus a 105.9 average over time.

Re

Re