By Stephen Kalin and Saif Hameed

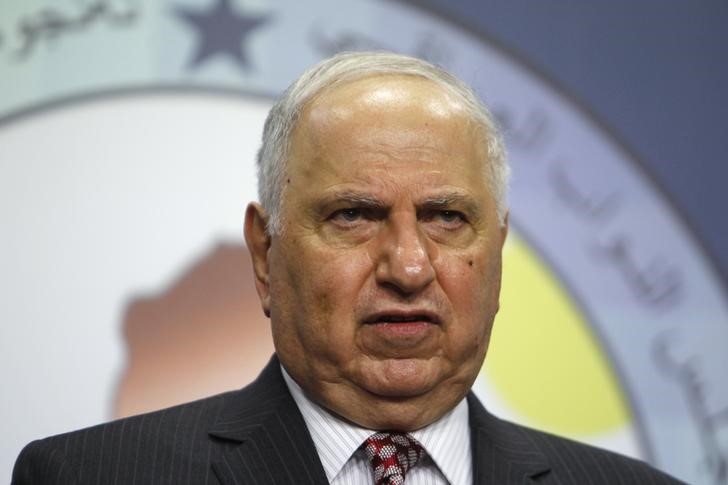

BAGHDAD (Reuters) - Ahmed Chalabi, the smooth-talking Iraqi politician who pushed Washington to invade Iraq in 2003 with discredited information on Saddam Hussein's military capabilities, died on Tuesday of an apparent heart attack.

Haitham al-Jabouri, secretary of parliament's financial panel that Chalabi had chaired, said attendants had found him dead in his bed in his Baghdad home. A news flash on Iraqi state television said the cause was a heart attack.

A secular Shi'ite, Chalabi rose to prominence as leader of the then-exiled Iraqi National Congress, which played a major role in encouraging the U.S. administration of former President George W. Bush to invade Iraq and oust Saddam.

"There are some people who will remember him in a good way, and there are others, to be honest, do not like and did not want his politics," said former prime minister Ayad Allawi.

"But regardless, Iraq lost a man who had an important contribution, important commitments towards the nation and he tried to offer what he could to this country."

Chalabi, born in 1944 into a wealthy Baghdad family, returned to Iraq shortly after Saddam's fall, the culmination of years of work abroad pressing and charming Washington to oust the man who ruled Iraq with an iron fist for decades.

He ultimately succeeded by persuading the United States that Saddam Hussein had links to al Qaeda and possessed weapons of mass destruction in the wake of the September 11 attacks, claims that later proved unfounded.

After the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, he could often be seen in Baghdad flanked by dozens of bodyguards as he forged ties with political figures and powerful clerics.

CHEQUERED CAREER

Once viewed in Washington as its preferred future Iraqi leader, he lost favour among his American benefactors amid accusations that he had passed information to arch-foe Iran.

"He pursued all roads in order to achieve a goal he believed in, which was overthrowing the oppressive regime of Saddam and build a civil state," said Mithal Alusi, a secular lawmaker. "He followed any path possible, be it accepted or not."

Chalabi was later charged with leading the purge of Saddam Hussein's Baath Party, a move that would prove costly.

Al Qaeda capitalised on the security vacuum that followed, triggering a sectarian civil war with attacks on the majority Shi'ite population that would plunge Iraq into chaos for years.

At one point, Chalabi's name was floated as a candidate for prime minister after he managed to skilfully navigate Iraq's Byzantine politics and forge alliances with the most powerful forces of the day.

But he never managed to rise to the top of Iraq's sectarian-driven politics. His fallout with his former American allies also hurt his chances of leading Iraq.

"Everyone was against him and accused him of being an agent, but they all secretly approached him and sought for him to be their bridge to the Americans," said Alusi.

Chalabi's career was chequered. A former top banker, he was convicted of embezzlement by a court in Jordan and sentenced in absentia to more than 20 years in prison.

His tainted reputation never curbed his ambitions.

In the last few months, Chalabi had been working on an investigation into alleged irregularities in banking transactions in Iraq, a close associate told Reuters.

He held regular discussions about Iraq with academics, political supporters, friends and journalists who gathered at his home, styled after houses by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright and featuring a large swimming pool.

Senior politician Muwaffaq Rubaie, who said Chalabi was in good health when they last met over the weekend, described him as "a frighteningly intelligent guy".