(Bloomberg) -- Four months ago, Saudi Arabia’s devotion to its decades-old oil partnership with the U.S. was stronger than ever.

President Donald Trump was poised to choke off crude exports from the kingdom’s political nemesis, Iran. And the Saudis, shunned by other nations after the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, were readily obliging the White House with record supplies.

But the Trump administration stunned Riyadh by softening its crackdown on Iran at the last minute, allowing many customers to continue buying and triggering a crash in oil prices. Since then, the Saudis’ trust in their main political ally has frayed.

When the kingdom meets with allied oil producers in the Azeri capital of Baku this weekend, that sense of betrayal may loom large in its decision-making.

“The way that the Saudis were misled by the U.S. president concerning Iran sanctions is something that they can still taste,” said Ed Morse, head of commodities research at Citigroup Inc (NYSE:C). in New York.

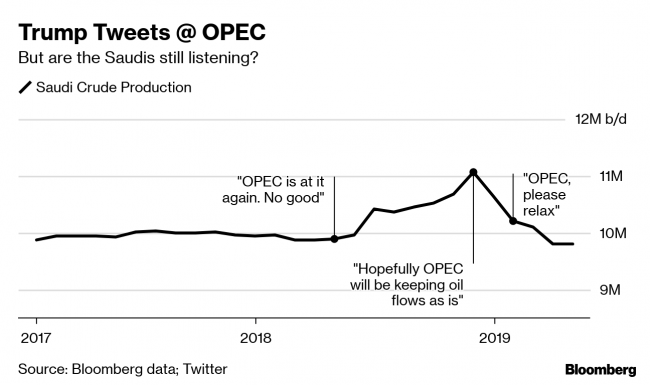

Although Trump has once again called on the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries to moderate prices, the group’s biggest member is doubling down on a strategy to support them, at least for now. Crude climbed to a four-month high above $58 a barrel in New York on Wednesday as U.S. inventories shrank.

A 24-nation coalition known as OPEC+, made up of members of the cartel and former competitors such as Russia, has entered its third year of curbing supply in order to defend crude prices. While they’ve helped engineer a 25 percent recovery in Brent this year, current prices of about $67 a barrel remain well below the levels that most of the producers need to cover government spending.

Saudi Arabia requires an average oil price of $80 a barrel to fund plans for increased spending this year, according to Bloomberg calculations based on its 2019 budget. The kingdom’s financial pressures are growing as Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman pursues a radical overhaul to diversify the economy away from oil, while waging a proxy war in Yemen and dealing with the fallout from the Khashoggi killing.

That aim is driving the Saudis to stick with their strategy, despite the threat of potential antitrust legislation known as NOPEC, which gained momentum in the U.S. Congress after Khashoggi’s death in Istanbul in October.

When Trump tweeted on Feb. 25 that OPEC should “relax” its stance on tightening supplies, he was gently rebuffed by Saudi Arabian Energy Minister Khalid Al-Falih, who said he favors maintaining output curbs in the second half of the year.

Al-Falih’s defiant tone has been backed up by the kingdom’s recent actions.

Saudi Arabia has cut production by even more than it pledged in the OPEC+ accord, and will continue to do so next month, a Saudi official familiar with the policy said this week. Its crude shipments to the U.S. fell in February to the lowest since at least 2010, according to the Energy Information Administration.

It’s a marked contrast with last autumn. Back then, the Saudis bowed to intense pressure from Trump as his administration’s promises to squeeze Iranian supply to “zero” propelled crude prices to a four-year high above $86 a barrel.

New Strategy

To avert a shortage, and assist Trump’s diplomatic campaign against Tehran, the kingdom raised production, eventually reaching record levels above 11 million barrels a day. But in early November the president chose to let a number of Iran’s customers keep buying, and the ensuing oil oversupply sent prices slumping by 35 percent in the fourth quarter of last year.

“We’re going to see quite a different Saudi Arabia maybe than what we saw in the fall,” said Mohammad Darwazah, a director at Medley Global Advisers. “I don’t think they’re going to be as accommodative.”

A panel drawn from key nations in the OPEC+ alliance, the Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee, is gathering in Azerbaijan this weekend to review oil markets before the whole group meets next month and again in June.

The Saudis will probably repeat their preference to prolong the accord and try to persuade Russia to follow suit, Darwazah said. With prices down around 22 percent from last year’s October peak, the pushback from Washington won’t be so acute.

The kingdom could nonetheless soften its position if production losses in Iran and Venezuela, now both under U.S. sanctions, escalate enough to cause a shortfall.

“This U.S. role, with sanctions on two big exporters, is really the big wild card for the market,” said Mike Wittner, head of oil market research at Societe Generale (PA:SOGN) SA in New York. “Could the Saudis surge production again? Absolutely.”

Saudi Arabia’s decades-long reliance on U.S. diplomatic and military support, the current ties between Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman and the Trump administration, and the lingering threat of NOPEC legislation mean that Riyadh would likely still heed a sufficiently urgent call from Washington.

Unplanned Cutbacks

Iran’s production has already fallen to the lowest since 2013 amid the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions, following Trump’s decision to abandon an accord on the country’s nuclear program.

Venezuela’s output has plunged to the lowest in decades amid a spiraling economic crisis, which culminated this week in widespread electricity blackouts, and as the U.S. deploys sanctions against President Nicolas Maduro’s regime for fraudulently clinging to power.

Both countries could see oil production slump further in coming months, especially as the U.S. ban on Venezuelan crude trade takes full effect in late April and measures against Iran could be tightened in early May.

While that could induce Saudi Arabia to raise production, there’s a critical difference between now and 2018, Societe Generale’s Wittner said. In the autumn the kingdom pre-empted an anticipated supply disruption but this time it will be reactive.

“They’ll wait and see those losses first,” said Wittner. Last year “the Saudis were left hanging, having already ramped up production. Those memories are very fresh.”

(Updates with oil price in sixth paragraph.)