By Ahmed Aboulenein

CAIRO (Reuters) - Egypt will hold a long-awaited parliamentary election, starting on Oct. 18-19, the election commission said on Sunday, the final step in a process to bring back democracy that critics say has been tainted by widespread repression.

Egypt has been without a parliament since June 2012 when a court dissolved the democratically elected main chamber, dominated by the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood, reversing a major accomplishment of the 2011 uprising that toppled autocrat Hosni Mubarak.

The election had been due to begin in March but was delayed after a court ruled part of the election law unconstitutional.

A second round of voting in the two-phase election will take place on Nov. 22-23, the election commission told a news conference. Voting for Egyptians abroad will take place on Oct. 17-18.

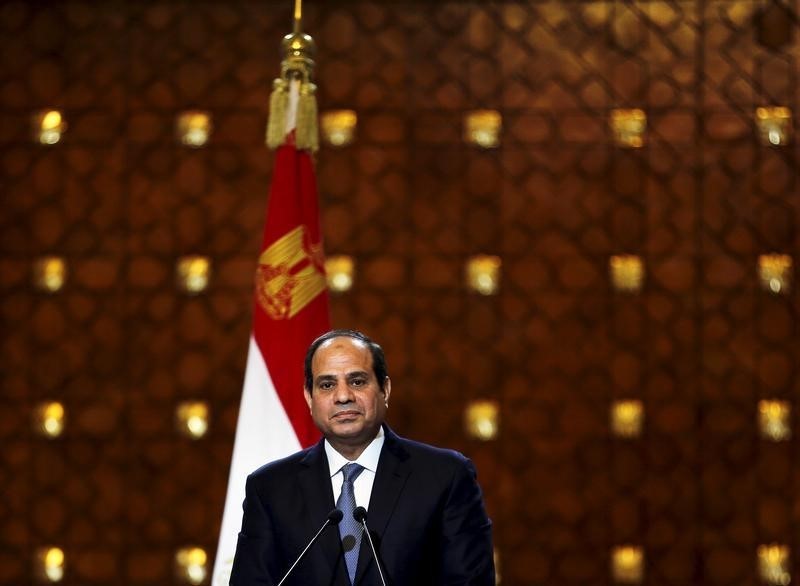

The then military chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who went on to become president, toppled Egypt's first freely elected president, Mohamed Mursi of the Muslim Brotherhood, in 2013 after mass protests against his rule.

The army then announced a 'roadmap' to democracy in Egypt, the most populous Arab state and ally of Western powers.

That announcement was followed by the toughest crackdown on Islamists in Egypt's history. Security forces killed hundreds at street protests and thousands were arrested.

Secular activists were later rounded up mostly for protesting without permission from the police.

The government says the election is proof of Egypt's commitment to democracy.

In the absence of parliament, Sisi has wielded legislative authority to curtail political freedoms but also introduced economic reforms.

"The question will remain: will this parliament be an effective check and balance against the executive? There are some signs it may, due to the likely prevalence of big-business interests within it, be argumentative on issues pertaining to economic policy," said H.A. Hellyer, nonresident fellow at the Brookings Centre for Middle East Policy in Washington.

"But on issues of political reform, legislative reform, or security sector reform, there probably won't be much appetite to affect much change from within this forthcoming parliament."

The House of Representatives is made up of 568 seats, with 448 elected as individuals and 120 through winner-takes-all lists, with quotas for women, Christians and youth. The president may appoint a number of people to the house, not exceeding 5 percent of its makeup.

Some political parties criticise the emphasis on individuals as a throwback to Mubarak-era politics, which often favoured candidates with wealth and family connections.

With Mubarak's National Democratic Party gone, loyalists have scrambled to form alliances to secure Sisi a sizeable bloc of support.

Hardcore Brotherhood supporters are likely to boycott the vote while Egyptians who had backed the group but then became disillusioned with it during Mursi's troubled rule could either vote for other Islamists or pro-Sisi candidates.

The Brotherhood won nearly every election since Mubarak's ouster but has now been driven underground as its leaders face the death penalty or long jail sentences.

Egypt will prepare for elections facing several challenges, including the struggle to revive an economy battered by years of political turmoil following Mubarak's ouster and a stubborn Islamist militant insurgency based in the Sinai.

Those militants, affiliates of the Islamic State group that holds large chunks of Iraq and Syria, have killed hundreds of soldiers and police since Mursi's downfall.