For much of the year, the bond market has been embracing expectations that the Federal Reserve’s interest rate increases have peaked or were about to peak. The underlying logic centered on the ongoing slide in inflation following 2022’s spike.

Inflation has continued to ease, but the market has continually discovered that the future’s still uncertain as the Fed pushed ahead with more hikes.

The ”wisdom” of the crowd may be in the early stages of another reality check as the Treasury market flirts with repricing yields upward. It’s too soon to say if the latest uptick is noise or the start of a trend that marks a new run of higher yields that takes out previous highs.

Even if the point of peak rates has finally arrived, the question turns to: How long the accumulated rate hikes hold? For longer than expected, predicts Neel Kashkari, president of the Minneapolis Fed and a voting member of the central bank committee that sets monetary policy. “I think we’re a long way away from cutting rates,” he advises.

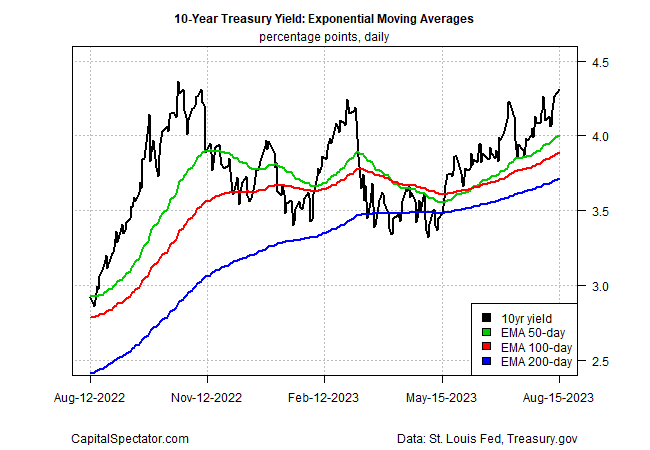

Meanwhile, the Treasury market is repricing yields higher again. Notably, the benchmark 10-year rate is pushing up against the high for the year. Using a set of exponential moving averages for this key rate suggests the bias is shifting to the upside once more.

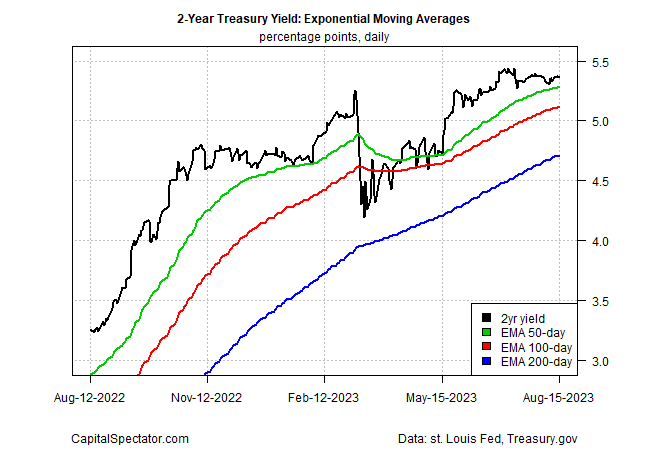

A similar profile applies to the policy-sensitive 2-year yield, which is trading just below its 2023 high.

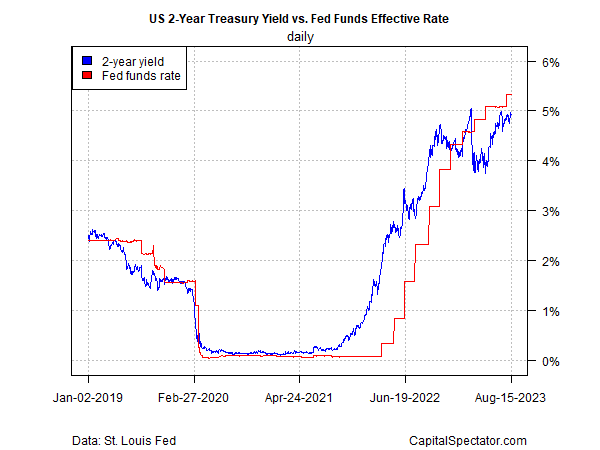

Keep in mind that the 2-year yield (widely followed as the market’s main guesstimate for where the Fed’s target rate is headed) has been forecasting the central bank’s rate hikes have passed and/or rate cuts are near. The scorecard so far: the Treasury market has been consistently wrong.

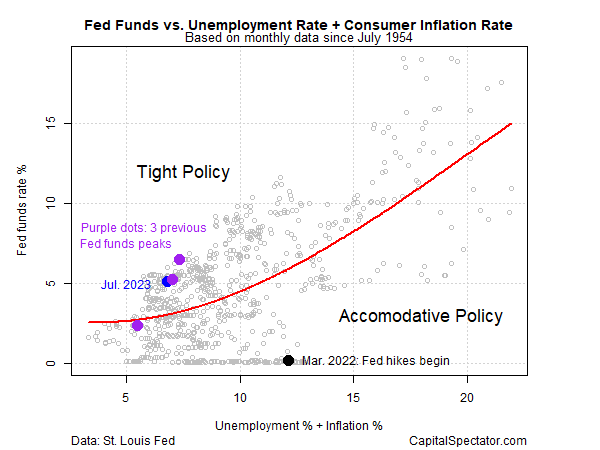

Relative to inflation and unemployment, the current Fed funds rate (5.25% to 5.50% range) is moderately tight. The implication: assuming that inflation continues to ease, as it has for much of this year, the Fed can let its tighter policy coast and continue to exert a fair amount of disinflationary pressure. Indeed, if inflation falls further, simply leaving rates unchanged would amount to passive tightening.

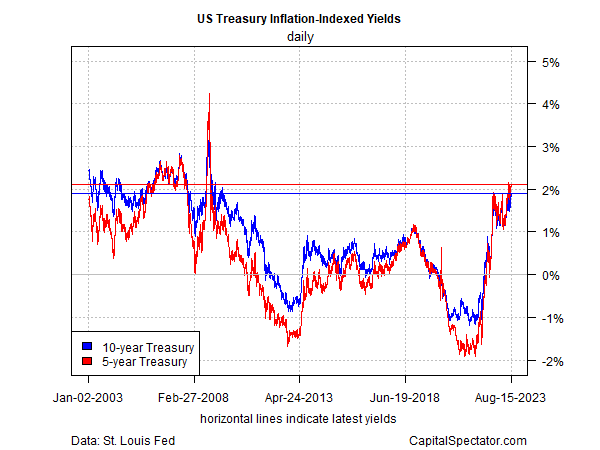

That backdrop has helped push up real (inflation-adjusted) Treasury yields to the highest in roughly 15 years, based on inflation-indexed government bonds.

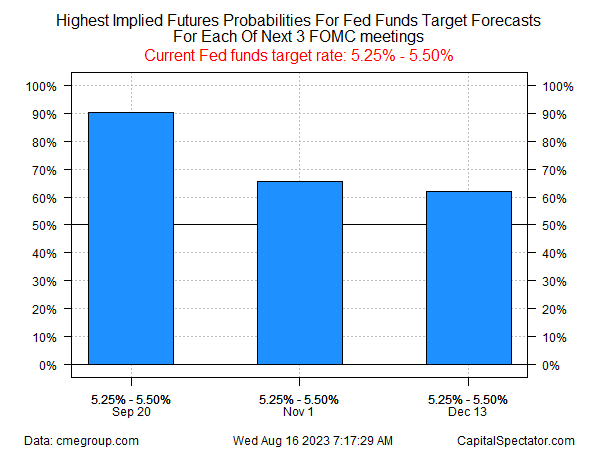

In turn, the hawkish tilt and easing inflation offer a degree of confidence in some corners of the market for thinking that the Fed’s rate hikes have peaked. Notably, Fed funds futures continue to price in the end of rate hikes.

But given the market’s track record to date, there’s reason to stay cautious that the future is no longer mysterious. Yesterday’s hotter-than-expected retail sales data for July offer a fresh excuse to wonder if the Fed is comfortable with the current policy with an economy that still looks resilient.

Some analysts see opportunity from an investment perspective, reasoning that with yields near the highest in years, the ability to lock in relatively steep payout rates is compelling.

“Going up the US curve to 10 year-plus is now looking more and more interesting because we’re at the top of the range and more fundamentally the real yield is covering the trend GDP,” says Steven Major, global head of fixed-income research at HSBC (LON:HSBA).

Is this really the top? No one knows, but at least one thing is clear: we’re closer to the peak vs. last week, last month, and a year ago.