By Hooyeon Kim

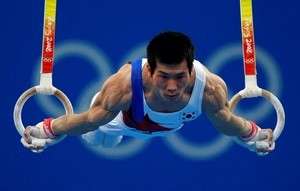

SEOUL (Reuters) - Twelve years have passed since South Korean gymnast Yang Tae-young stood stony faced on the podium to collect his Athens Olympics bronze medal, while beside him America's Paul Hamm beamed ear-to-ear with the gold draped around his neck.

Time, apparently, does not heal all wounds.

Yang was at the centre of one of the Olympics' biggest controversies when a judging error at the 2004 Games docked him 0.1 of a point for his parallel bars routine, enough to cost him gold in the all-around competition.

The governing body of gymnastics (FIG) acknowledged that Hamm had been handed the gold in error but refused to change the result and redistribute the medals as officials said the South Koreans had failed to lodge their protest in time.

The FIG suspended the judges in question, and its president, Bruno Grandi, wrote to Hamm suggesting he give the gold to Yang in the ultimate show of sportsmanship.

After Hamm refused, Yang took case to the Court of Arbitration for Sport but his appeal was dismissed.

"I regret it even more now as a coach than I did when I was an athlete because I can no longer compete,” Yang told Reuters in a recent interview. “I want to go back in time and try again."

While missing out on the gold medal under those circumstances was hard enough for Yang to swallow, it would also have huge financial implications.

The South Korean government awards monthly stipends and lump sums to Olympic medal-winning athletes, with the rewards determined by a scoring table.

An Olympic gold medal is worth 1 million won ($840) per month, while the stipends for silver and bronze medals were roughly doubled in 2011 to 750,000 won and 525,000 won per month, according to the Korean Olympic Committee (KOC).

The lump sums awarded to individual medallists depend on a range of factors including the number of medals won, government budget etc, but a gold medal brings in roughly 40 million won more than a bronze medal.

ADDITIONAL BONUSES

Short track speed skater Park Seung-hi received more than 120 million won from the KOC after picking up two golds and a bronze medal at the 2014 Sochi Winter Games.

That figure ballooned to over 300 million won when additional bonuses from other organisations were included, according to local media reports.

There were calls in South Korea for Yang to be rewarded as a gold medallist but the Korean Sports Promotion Foundation confirmed this did not transpire.

Yang instead receives a bronze medal stipend with other monthly payments for medals he won in other international competitions, though they are valued less than Olympic medals, according to the foundation's guidelines.

“Everyone thought I would receive the gold medal pension, if not the medal itself. I did too," said Yang, who now helps coach the national gymnastics team. "But it didn’t work out that way.”

Two years after the controversy, the FIG scrapped the perfect 10 score.

While many say Yang's experience gave the FIG the impetus to make the change, the South Korean said he did not believe the scoring overhaul had much of an effect.

“People said the rules changed because of me, but I only made it tougher,” he said, adding that he believed the new rules had lead to more injuries in the sport.

"Has it made anything fairer? I don’t know. I don’t think things have changed since then."

With 2012 Olympic vault gold medallist Yang Hak-seon struggling with an Achilles injury, gymnastics medals in Rio will be hard to come by for South Korea.

One of the country's emerging talents, Park Min-soo, said he was not worried about the potential for judging mistakes in Rio.

I’m not scared of any judging mistakes. I trust in the time I put into practising,” he said.

“I have no fear, only confidence.”

($1 = 1,188.1000 won)