By Svetlana Reiter and Vladimir Soldatkin

MOSCOW (Reuters) - Human rights group Amnesty International can return to the Moscow office it was evicted from this week, a Kremlin human rights adviser said on Thursday after discussing the matter with President Vladimir Putin.

Amnesty has been a vocal critic of Russia over its bombing campaign in Syria and had said it believed the eviction might be part of an official crackdown on civil society groups.

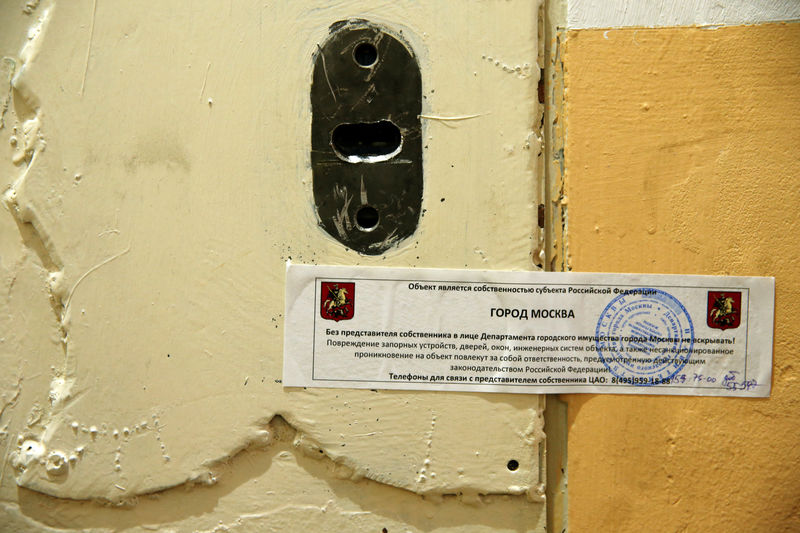

Amnesty staff had turned up at their office in central Moscow on Wednesday morning to find the locks had been changed and the power cut off. The Moscow city government, from which Amnesty leases the premises, said it was owed rent, but the group said payments were up to date.

Mikhail Fedotov, head of the Russian Human Rights Council which formally reports to the Kremlin, told Reuters he had met Putin and discussed the matter.

"The lease has been restored completely. They (Amnesty) will be able to return to the office in the nearest future. Putin was informed of this," Fedotov said.

Soon after that meeting took place, John Dalhuisen, Amnesty International's Europe director, told Reuters that the group had been contacted by Vladimir Yefimov, head of the Moscow city property department, who said there may have been a mix-up.

According to Dalhuisen, Yefimov invited Amnesty for a meeting on Monday. Friday is a public holiday in Russia.

"I would say this was promising and we look forward to the meeting and resolving this issue," Dalhuisen said.

Amnesty said the city authorities had been ignoring its requests for talks.

Moscow's city property department could not immediately be reached for comment.

Amnesty, which was founded in London, frequently criticises the Russian authorities over what it says are human rights violations. It alleges in particular that Russia and its allies have killed large numbers of civilians with air strikes on the Syrian city of Aleppo. Moscow denies this.

After news of the eviction emerged on Wednesday, the U.S. State Department expressed its concern.

Rights groups that criticise the Kremlin and receive foreign funding have come under growing pressure in Putin's Russia.

Kremlin officials have accused some foreign-backed civil society groups of working on behalf of Western governments to foment unrest and replicate the revolutions that forced out pro-Russian leaders in several former Soviet states.

As part of the official crackdown, some non-governmental organisations have been designated as "foreign agents", which makes them subject to intense scrutiny.