By Hugh Bronstein

BUENOS AIRES (Reuters) - The mysterious death of an Argentine prosecutor just days after he accused the president of directing a cover-up in the bombing of a Jewish community centre two decades earlier has jolted the country with accusations of foul play coming from all sides.

The body of Alberto Nisman, lead investigator into the 1994 car bomb that killed 85 people, was found in his apartment on Sunday night, a handgun by his side along with a single shell casing.

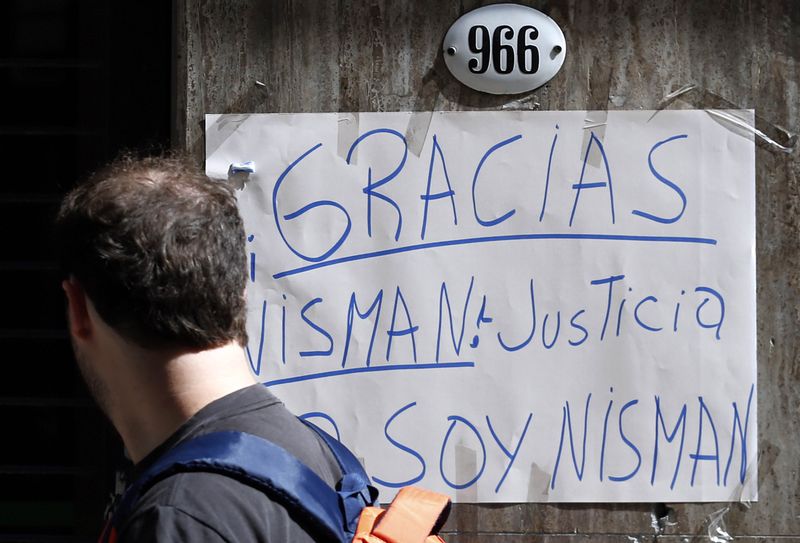

He had been scheduled to present his findings in Congress on Monday and his death sparked street protests over the slow pace of justice for the attack on the AMIA Jewish centre in 1984.

Officials said Nisman apparently committed suicide but his former wife, Sandra Arroyo, said on Tuesday that she did not believe he killed himself, and some Argentines suspect the government might be behind his death.

"Murderer!" some among a crowd of 2,000 shouted as they hammered at police barricades surrounding the presidential palace. Hundreds more demonstrated outside the presidential residence as Nisman's death dominated Argentine news programs and social media.

President Cristina Fernandez and her allies also say there appears to be more to it than a simple suicide although they have not said who they think was part of any conspiracy.

Viviana Fein, the state prosecutor handling the case, said Nisman was alone when he died but that she has not discarded the possibility of there being "some type of induction or instigation" of the suicide.

"Was it a personal decision or was he pressured?" said Juliana Di Tullio, a government-allied member of the lower house of Congress.

A government source who asked not to be named told Reuters the Fernandez administration believes the death was linked to a struggle within the state intelligence services.

The head of Argentine intelligence was replaced in December, resulting in the firing of agents who had been helping with Nisman's investigation. Nisman had accused agents from another faction within the state intelligence apparatus of being part of Fernandez's alleged plot to clear the Iranian suspects.

Nisman alleged last week that Fernandez wanted to whitewash the 1994 bombing and normalize relations with Iran in order to trade Argentine grains for Iranian oil.

Argentina has a $7 billion annual energy gap, complicating the government's efforts to jumpstart a weak economy.

Fernandez and her ministers dismissed Nisman's charges last week as ridiculous. Since his death, they have raised questions about his activities earlier this month, when he rushed back from vacation to level the accusations against her.

"Who was it who ordered Nisman to come back to the country on Jan. 12 ... interrupting a family vacation that was not set to end until Jan. 20?" Fernandez asked on a Facebook post, putting quotation marks around the word 'suicide' when she referred to his death.

"Who can believe ... he would cut his vacation short without telling the judge handling the case, and hand over a 350-page complaint that would have had to be prepared earlier? Or could it be that someone gave him the complaint when he got back?"

Late on Tuesday, the government published a letter from the intelligence service stating that two alleged agents Nisman mentioned in his accusations had in fact never worked for the agency. Several officials have picked holes in his report.

The case could have an impact on Argentina's presidential election in October. Opposition candidates Mauricio Macri, the mayor of Buenos Aires, and Congressman Sergio Massa criticized Fernandez's handling of the crisis, saying she should have addressed the nation on television rather than Facebook.

"This could have calmed the situation," Massa said.

Fernandez has been in power for eight years and is barred from running for a third consecutive term.