By Padraic Halpin

DUBLIN (Reuters) - Ireland's state broadcaster will appeal on Tuesday for a court to let it report a lawmaker's speech in parliament that accused a billionaire of obtaining sweetheart bank loans, a ruling that could determine how far Irish courts can go to muzzle the press.

At issue is whether "absolute privilege" of lawmakers to speak up in parliament - and news organisations to report their remarks - trumps the wide power of Irish courts to halt publication of stories that they rule may be libellous.

Ireland's domestic media have so far mainly complied with a court order banning reporting of accusations against billionaire press baron Denis O'Brien, even though lawmaker Catherine Murphy stood up in parliament last week to repeat the allegations.

Instead, the court-imposed media blackout has itself become the story.

"I do not believe it's tenable that media outlets in Ireland cannot report on what is taking place in our parliament and media outlets outside of Ireland can and are," Irish Transport Minister Paschal Donohoe told state broadcaster RTE.

"That is not acceptable."

The leader of Ireland's main opposition party, Fianna Fail, said the country was on the verge of a "constitutional crisis" over the issue.

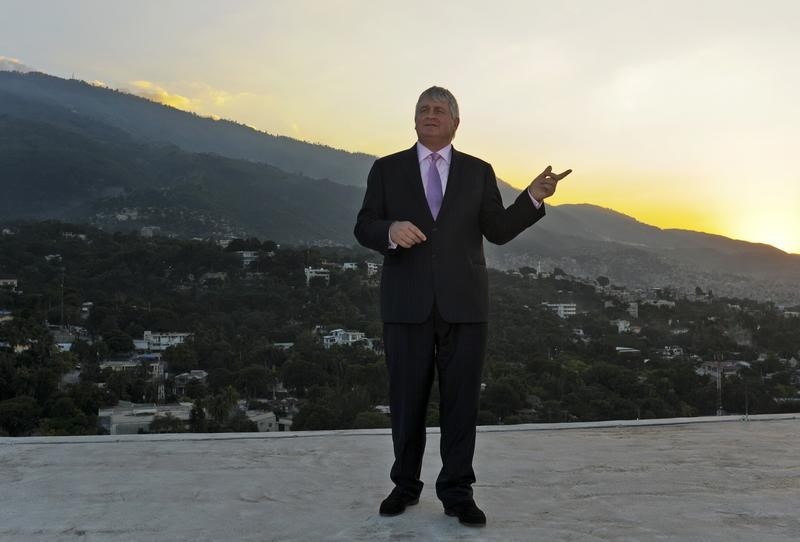

O'Brien is one of Ireland's most powerful press barons, owner of its biggest circulation newspaper, the Irish Independent, as well as four other national newspapers, 13 regional newspapers and two major national radio stations.

He denies wrongdoing and says he has a right to privacy in his financial affairs. On May 21, he obtained a court order preventing RTE from airing a report about his past business dealings.

Last week, Murphy stood up in parliament to accuse him of paying a below-market interest rate for loans from the state-owned Irish Banking Resolution Corporation (IBRC), the wind-down vehicle for a bank that collapsed during the 2008 financial crisis.

The details of Murphy's speech have been reported in some British media, but have generally not appeared in Irish news reports, even though the speech is available in transcripts on parliament's website, http://www.oireachtas.ie.

O'Brien's spokesman told RTE: "Most of what she said was untrue but not all of it. Catherine Murphy has presented as facts figures that are not correct and she has made statements that are fundamentally wrong."

The spokesman declined to elaborate. He told Reuters he had been advised that it would breach the court order to go into further detail.

Murphy said in a statement she stood by her right, as member of parliament, to put information in the public interest into the public domain: "The people that continue to accuse me of falsehoods refuse to provide evidence to refute any of the issues I've questioned in the Dáil (parliament)."

SHATTERED FAITH

Some Irish news organisations say the allegations are a matter of public interest, and that no court should be allowed to censor a speech made openly on the floor of parliament, granted "absolute privilege" by the constitution.

"Faith in the media's ability to do its job will be shattered if this challenge is not faced head on. This is a defining moment for the media in Ireland," said Seamus Dooley, secretary of the National Union of Journalists in Ireland.

Irish courts do not comment on matters before them.

As in many countries that inherited the British legal system, Ireland's courts have broad powers to issue injunctions preventing publication of news stories that may be libellous. Often details of the injunctions themselves must be kept secret, since publishing them would reveal the story itself.

RTE says it is fighting against the original injunction in court, and will seek a ruling on Tuesday that its constitutional right to publish Murphy's remarks in parliament trumps the court order.

The Irish Times, which will also appeal to Dublin's High Court on Tuesday, said its lawyers had advised that reporting Murphy's statement in full would involve a breach of the injunction, and that it was not clear whether absolute privilege allowed it to disregard the court order.