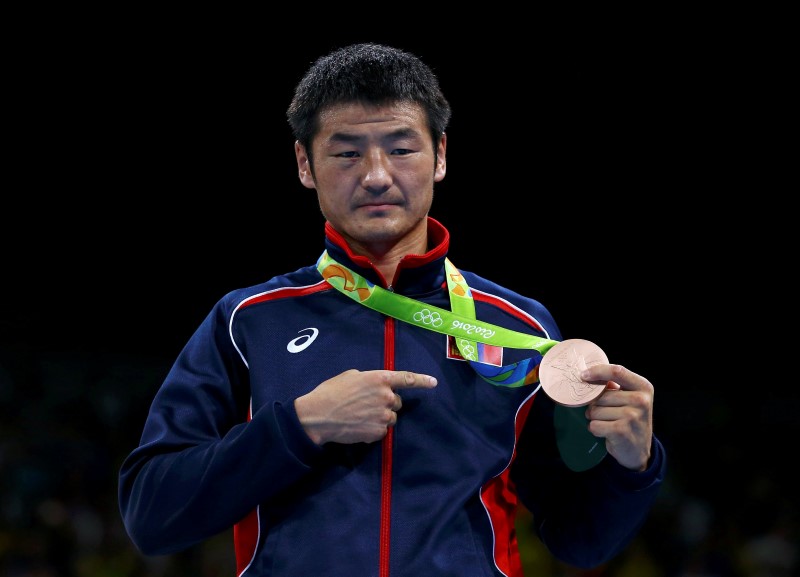

ULAANBAATAR (Reuters) - As mostly sports-mad Mongolians cheer on the country's two medallists at the Rio Olympic Games, deepening economic troubles at home mean the new government cannot afford to pay its athletes.

Four years ago, Mongolia was riding high on world-beating 12.3 percent economic growth, while five Mongolians won medals at the London Games.

The medals won in London contained traces of gold dug from Rio Tinto's Oyu Tolgoi copper mine (AX:RIO) (L:RIO) (TO:TRQ) in Mongolia, a flagship project that kickstarted billions of dollars in foreign investment.

But this year, the economy is facing a crisis, hit by plunging commodity prices and sinking investor confidence.

Mongolia's tugrik has been the world's poorest performing currency in August, dropping 8 percent against the dollar since the beginning of the month and 12.9 percent this year.

Its top athletes are also missing out on state payments.

Prime Minister Jargaltugla Erdenebat told a cabinet meeting this week the government owes 1.7 billion tugrik (£579,489.9) to 2,069 boxers, freestyle wrestlers, archers and other athletes granted lifetime monthly payments as part of a policy introduced nearly two decades ago.

The policy gave athletes between 500,000 and 4 million tugrik a month, with the highest going to Olympic gold medallists. That compares with an average salary of less than 871,000 tugrik.

The government plans to cut the salaries of the prime minister, the president and members of parliament by 30 percent. Lower-ranking government figures will take a 20 percent pay cut, though rank-and-file state employees will be spared, according to the Finance Ministry.

"The prime minister has the responsibility of seeing that the public officials are paid less," J. Ganbat of the ministry's fiscal policy department said in a statement posted on Mongolia's government website.

"About 3 percent in savings for this year could mean 8 billion tugrik in savings for next year.”

The new government under the Mongolian People's Party, elected in June, is having to deal with the consequences of a four-year slowdown, with growth expected to be flat in 2016 as a result of weaker demand for its coal and copper as well as disagreements with foreign investors.

Last week, the finance minister warned that the cash-strapped government would struggle to pay out wages and meet other costs, prompting a slump in sovereign dollar bonds.

On Thursday, the Bank of Mongolia raised its policy rate by 4.5 percentage points to 15 percent as a way of defending its flagging currency, it said in a statement.