By Stephen Eisenhammer

RIO DE JANEIRO (Reuters) - "Pure Island: a neighbourhood born ready-made," reads the glitzy brochure for the 31 tower blocks built for $880 million (£668.6 million) to house athletes for the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro next month.

After the Games, this is meant to become Rio's newest community, a bustling legacy of the 17-day sporting event.

But there's one thing missing - residents.

Developers say they have sold just 240 of the 3,600 apartments that go for between 750,000 and 3 million reais (£175,277 to £700,910).

Buyers are returning apartments, a sales source said, put off by Brazil's economic crisis and the scant appeal of being lonely occupants of a space stretching more than 100 football pitches in a still-remote region of Rio.

The largest athlete's village in the history of the Games is a visceral monument to now-faded optimism. Planned when Brazil was booming, its harnessing of private sector wealth was meant to set the gold standard for a sustainable Olympics.

Instead, the worst recession in generations pushed the luxury apartments out of reach.

"Pure Island", or "Ilha Pura" in Portuguese, is one of multiple projects, including the Olympic Park and the 8 billion reais regeneration of Rio's port area, funded in partnership with developers but now stalling.

The development, complete with a landscaped central park, fountains, tennis courts and swimming pools, was spookily deserted on a recent visit and felt more like a film set than a new neighbourhood.

The joint venture between developer Carvalho Hosken and construction company Odebrecht [ODBES.UL] says it always planned to sell most of the luxury apartments after the Games. But Mauricio Cruz Lopes, director general for the project, admitted sales are well below the target of 1,000 properties by now.

"When this project was planned there was an optimism and growth across all of Brazil," said Cruz Lopes. "Now the situation is completely different."

TWO-WEEK EVENT

Mayor Eduardo Paes likes to highlight that 57 percent of the nearly 40 billion reais being spent on the Olympics is private money. London's Olympics by contrast was over 80 percent publicly funded.

Rio used public-private partnerships (PPPs) to get companies to cover the cost of new venues in return for permission to build real estate. About 5 million square meters of land has been opened to developers, more than three times that of London's Canary Wharf.

But companies that entered into the deals are now struggling and critics say the city missed a chance to build affordable housing like London did.

Instead, developers accentuated a gaping class divide with luxury property on the city's western periphery. Now, with Brazil in its worst recession since the 1930s, demand has crashed and Rio house prices are down 20 percent in real terms over the past year.

The municipal government removed thousands of people from their homes, some to improve access to the Olympic Park, others to clear the way for new transit routes.

Billions of dollars were spent to build bus lines and a subway extension to improve access to Olympic developments while laws were changed to increase permitted building heights.

"The worst is that it's all for an event that lasts two weeks," said Marcia Lemos, 58, whose home by the Olympic Park was destroyed. She is fighting for compensation in the courts, but expects to get nothing.

Despite city assertions Rio is being improved for everyone, critics say developments do little to improve conditions for the 20 percent of the metropolitan area's 12 million people who live in slums or ease snarling traffic for poor residents whose commutes from Rio's outskirts can take two or three hours.

"They overbuilt and they misbuilt," said Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College in the United States and author of "Circus Maximus," a comparative study of the economics of hosting the Olympics. "They built high luxury condos at a time when the market was about to go bust."

Ultimately, the Brazilian public could be on the hook because projects were financed by state banks or public investment funds.

Ilha Pura, for example, was built with a loan of 2.3 billion reais from state lender Caixa Economica Federal (CEF.UL).

Porto Maravilha, the port regeneration, was paid for by FI-FGTS, a public investment vehicle financed by payroll deductions. The fund was meant to turn a profit by selling building rights, but has only sold 9 percent of its stock.

Cruz Lopes said he is still confident Ilha Pura will be able to pay back the loan, due in 2025.

Cassio Viana de Jesus, who oversees the Porto Maravilha investment, said the fund can still make its targeted return of an accumulated 6.5 percent per year above inflation in 15 years.

There are no punitive consequences if it does not.

PATIENCE

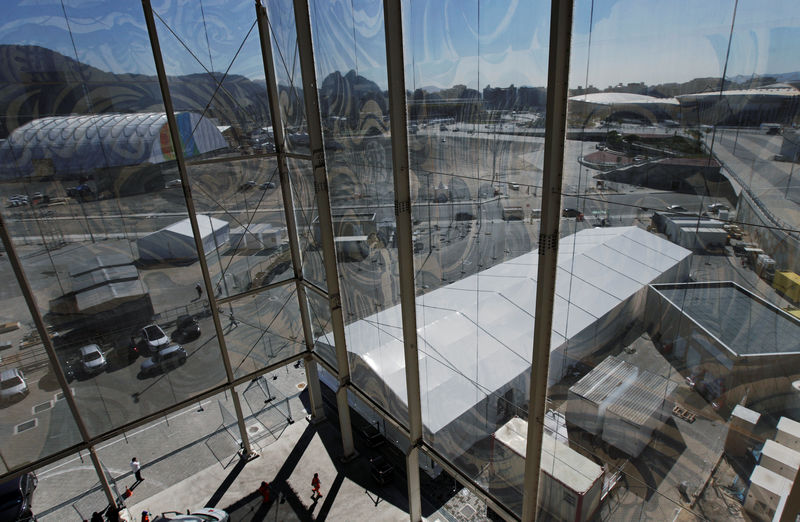

Just across the lagoon from Ilha Pura, finishing touches are being made to the Olympic Park, a triangular peninsula flanked by putrid water and equivalent to 160 football pitches. Its nine venues, that will hold 16 sports, are ready.

Workers in blue overalls tweak cables at the aquatics centre and handball arena near the triangle's tip. Both are temporary and will be removed after the Games to make room for real estate as part of a 1.4 billion reais PPP with Rio Mais, a consortium made up of Odebrecht, Carvalho Hosken and Andrade Gutierrez [AGIS.UL].

The master plan for the site, designed by U.S. engineering firm Aecom (N:ACM), includes a "legacy mode" for how the site will look in the future.

The plan, among thousands of documents relating to the Olympic Park reviewed by Reuters through a freedom of information request, shows a busy neighbourhood with apartment blocks hugging the waterline, a neat web of streets and a park, school, hotel and shopping mall. The site could be home to thousands of people.

This plan, which won an international competition in 2011 and which the contract viewed by Reuters states must be followed, forecasts a transformation of 5 to 7 years. Now, no one knows when it will happen.

Multiple sources with knowledge of the development said there were no imminent new residential or commercial projects planned.

Rio Mais did not respond to requests for comment.

Bill Hanway, head of Aecom's sports division that designed the master plan, said Brazil's economy had slowed the timeframe.

Asked if the site might appear abandoned, he said: "It might look like that from the air." From the street the site will feel more developed, he explained, due to permanent structures used as offices and a hotel after the Games.

"It's important to be patient," said Jorge Arraes, Rio's municipal chief for PPPs. "If it's abandoned in 10 years, that would be a scandal, but I don't think it will be."

Even a medium-term delay leaves a vital piece of the jigsaw missing from early years of the legacy plan.

Three of the Olympic sports arenas are meant to be transformed into a training centre for athletes and a public school. Their viability will be hit if adjoining land is a deserted concrete wasteland.

There are doubts too over the contracts themselves. Police are investigating Olympic contracts for possible wrongdoing because the same companies that are implicated in a massive corruption scandal surrounding oil producer Petrobras (SA:PETR4) also built most of the Olympic projects.

The city continues to repeat that "it's not what Rio can do for the Games but what the Games can do for Rio."

Zimbalist, the economist, is quick to give his verdict: "That's baloney."